Forces Engaged: Great Britain (Royal Army/Royal Navy) -

Battle Cruiser Fleet and escorts: (4 battlecruisers, 4 light cruisers)

HMS Lion (Flagship, VADM Beatty - Lion-class battlecruiser) 8 × BL 13.5-inch Mk V guns (4 twin turrets), 16 × 1 – BL 4-inch Mk VII guns, 2 × 1 – 21-inch Mk II submerged torpedo tubes, 28 knots

HMS Tiger (Lion-class battlecruiser) 8 × BL 13.5-inch Mk V guns (4 twin turrets), 12 × 1 – BL 6 inch Mk VII guns, 2 × 1 – 3-inch AA guns, 4 × 21-inch torpedo tubes, 28 knots

HMS Queen Mary (single-ship class) 8 × BL 13.5-inch Mk V guns (4 twin turrets), 16 × 1 – BL 4-inch Mk VII guns, 2 × 1 – 21-inch Mk II submerged torpedo tubes, 28 knots

HMS New Zealand (Indefatigable-class battlecruiser) 8 × BL 12-inch Mk X guns (4 twin turrets), 16 × 1 - BL 4-inch Mk VII guns, 2 × 1 submerged 18-inch torpedo tubes, 25 knots

(We'll talk about this in a bit, but these ships were among the most problematic ever launched - "eggshells armed with hammers" - lightly armored but armed with battleship cannon, the product of the wildly creative mind of ADM "Jackie" Fisher, the genius behind the dreadnought battleship.

While the dreadnoughts were an unqualified success and the defining warship of their age, I'll get this over upfront and just say that the entire "battlecruiser" concept was irretrievably flawed and a death sentence for many of the men who sailed in them. They were not battleships but looked and sailed like them, and because of that they were went where they should never have gone and in so doing killed their tens of thousands.)

The First Light Cruiser Squadron was assigned to the Battle Cruiser Fleet as escorts. This unit included four light cruisers of the "Town" class, 6-inch gun-armed, 25-knot what would have probably been called "protected" cruisers at the time of the Battle of Tsushima Strait nine years earlier. Good ships for their time and purpose.

2nd Battle Squadron, Grand Fleet, and escorts: (6 battleships, )

HMS King George V (Flagship, VADM Warrender - King George V-class battleship) 10 × BL 13.5-inch Mk V guns (5 double turrets), 16 × BL 4-inch Mk VII guns, 4 × 3-pounder (47 mm) guns, 5 × machine guns, 3 × 21 inch torpedo tubes, 21 knots

HMS Ajax (King George V-class battleship) (as KGV)

HMS Centurion (King George V-class battleship) (as KGV)

HMS Orion (2nd Flagship, RADM Arbuthnot - Orion-class battleship) 10 × BL 13.5-inch Mk V guns (5 double turrets), 16 x BL 4-inch Mk VII guns, 3 x 21 in torpedo tubes (submerged), 21 knots

HMS Monarch (Orion-class battleship) (as Orion)

HMS Conqueror (Orion-class battleship) (as Orion)

2nd Battle Squadron was one of Grand Fleet's most powerful subunits. The six battleships were all so-called "superdreadnoughts" (because they mounted cannon larger than 12") and all relatively modern; Ajax, newest of the six, had been completed only just over a year earlier. All six were relatively similar, with five centerline double turrets.

The three Orions suffered from having their forward mast aft of the forward funnel; this tended to make the fire direction center located in the platform vulnerable to getting socked in with the cloud of coal smoke these ships emitted when under full power. They were the earlier version, and this problem was corrected in the King George V class.

Taken at face value this was a dangerous outfit. But it had some internal issues, the greatest of which being its commander, Vice-Admiral Sir George John Scott Warrender, 7th Baronet Lochend, KCB, a man of whom it was said later "never spoke in peacetime because he was deaf and everyone thought he must be thinking a lot. When war came, everyone said "Goodness gracious, what was he doing the whole time?" (Massie, 2004)

2nd Battle Squadron's escorts included the 3rd Cruiser Squadron (4 Devonshire-class armored cruisers, 4 8-inch and 6 6-inch cannon) and part of the 4th Destroyer Flotilla (7 destroyers of the Acasta (later renamed "K")-class, 3 x 4-inch cannon and 2 x 21" torpedo tubes)

While not directly involved in this phase of the action a small RN flotilla was located at Hartepool, one of the targets of the German raiders. This consisted of two light cruisers:

HMS Patrol (Pathfinder-class "scout" cruiser) 9 x 4-inch Mk IV guns, 6 x 6pdr guns, 2 x 18" torpedo tubes, 25 knots

HMS Forward (Forward-class scout cruiser) (as Patrol)

and four River-class destroyers armed with light (12- and 6-pounder) cannon and 2 18-inch torpedo tubes each.

Also at Hartepool were the coastal defence positions at Heugh and Lighthouse Batteries; three 6-inch Mk VII cannon and about 160 troops of the Durham Light Infantry (Royal Army).

So a total of 10 capital ships, 8 cruisers, and 7 destroyers: six battleships (with an escort of four armored cruisers and seven destroyers), four battlecruisers (with an escort of four light cruisers) in the main action, and another two scout cruisers and four destroyers in the earlier action at Hartepool.

No unified commander; VADM Warrender commanded 2nd Battle Squadron and escorts, VADM Beatty commanded the Battle Cruiser Fleet and escorts.

Deutsches Kaiserreich, Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial German Navy) -

The German forces engaged in both the raids on the east Yorkshire coast as well as the following actions near the Dogger Bank were entirely drawn from the Imperial Navy's High Seas Fleet (Hochseeflotte). The most critical element was the "1st Scouting Group " (I. Aufklärungsgruppe) consisting of four battlecruisers and an armored cruiser:

SMS Seydlitz (Flagship, KADM Hipper - single-ship class battlecruiser) 10 × 28cm (11 in.) SK L/50 guns (5 twin turrets), 12 × 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/45 guns, 12 × 8.8 cm (3.5 in)guns, 26.5 knots

SMS Moltke (Moltke-class battlecruiser) 10 × 28 cm (11 in.)/50 SK guns (5 twin turrets), 12 × 15 cm (5.9 in) guns, 12 × 8.8 cm (3.5 in) guns, 28 knots

SMS Derfflinger (Derfflinger-class battlecruiser) 8 × 30.5 cm (12 in.) SK L/50 (4 twin turrets), 12 × 15 cm (5.9") SK L/45, 4 × 8.8 cm (4×1), 4 × single 50 cm (20 in) torpedo tubes, 26.5 knots

SMS Von der Tann (single-ship class battlecruiser) 8 × 28 cm (11 in.) SK L/45 guns (4 twin turrets), 10 × 15 cm (5.91 in) SK L/45 guns, 16 × 8.8 cm (3.46 in) SK L/45 guns, 4 × 45 cm (18 in) torpedo tubes, 27-28 knots

SMS Blücher (single-ship class Große Kreuzer [armored cruiser]1) 12 (6 twin turrets)× 21 cm (8.3 in) SK L/45 guns, 8 × 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/45 guns, 16 × 8.8 cm (3.46 in) SK L/45 guns, 4 × 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes, 25 knots

(Note1: SMS Blücher was a troubled and, ultimately, a tragic vessel. She was designed in 1906, the same year as the first British battlecruisers of the Invincible-class but German Naval Intelligence was unable to learn anything about these British vessels before Blücher's design was finalized and monies for her construction allocated. The Imperial Marine Bureau (Reichsmarineamt or RMA) thought that the Invincibles were going to be big armored cruisers and when they turned out to be something entirely new, larger, and faster was unable, or unwilling, to either scrap this ship or redesign her.

The problem was with Blücher as designed is that she wasn't big, fast, or heavily-armed enough to be a battlecruiser but was way the hell bigger than any of the other Große Kreuzern. Here's a good illustration of that. The diagram below is from the 1914 Jane's Fighting Ships and shows Blücher's layout:

Now here's the diagram from the same source showing the layout of the preceding pair of Große Kreuzer, the Scharnhorst-class completed in 1906:

See the difference?2nd Scouting Group (II. Aufklärungsgruppe - four light cruisers and 18 large torpedo boats/small destroyers2):

The Scharnhorsts are still fundamentally old school armored cruisers, laid out in pre-dreadnought style: main battery with only four guns in two round, slab-sided turrets with the other four 8" cannons in a "central casemate" mounting along with a bunch of 6" and lighter weapons, reciprocating engines driving the ships at a top speed of about 22-23 knots.

But Blücher is a dreadnought.

An early dreadnought, yes; all the goddamn wing turrets testify to that. But she's bigger, faster, and she's an "all-big-gun" ship, the stamp of the Dreadnought Era. She "looks" more like a battlecruiser or small battleship than the older "big cruisers", so in a sense you can understand the tendency of the Imperial Navy leadership to slot her in with the big boys of the 1st Scouting Group.

But she wasn't. She wasn't even the equal of the genuine battlecruisers, and, as we'll see, they weren't anything like their larger cousins the dreadnought battleships.

Had she been assigned, say, to the lighter 2nd Scouting Group she would have been the biggest, strongest ship in that element. Instead she was the smallest, weakest part of I. Aufklärungsgruppe.

Eventually that would kill her and many of those who sailed in her.

SMS Stralsund (Madgeburg-class light cruiser) 12 × 10.5 cm (4.1 in.) SK L/45 guns, 2 × 50 cm (19.7 in) torpedo tubes, 27 knots

SMS Graudenz (Graudenz-class light cruiser) 12 × 10.5 cm (4.1 in.) SK L/45 guns, 2 × 50 cm torpedo tubes, 27.5 knots

SMS Kolberg (Kolberg-class light cruiser) 12 × 1 - 10.5 cm (4.1 in.) guns, 2 × 450 mm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes

SMS Strassburg (Madgeburg-class light cruiser) (as Stralsund)

Also two "flotillas" of light craft totaling 18 vessels;

I. Torpedobootflotilla (TBF), about 9 large torpedo boats2 - Hochsee-torpedoboot - of the 1906 class [3 x 10.5 cm guns; 3 x 8.8 cm gun; 3 x 45 cm (18 in) torpedo tubes, 34 knots] and

IX. TBF (probably 9 large torpedo boats Großes Torpedoboot of the 1913 class [3 8.8 cm (3.5 in) L/45 guns, 6 x 50 cm (20 in) torpedo tubes, 36 knots])

(Note2: Unlike many other Western navies, Germany did not choose to upsize their light escort vessels in the first decades of the 20th Century. Most of their potential enemies, in particular the British, discarded the original "torpedo boat" designs in favor of what was originally laid down as an anti-torpedo-boat or "torpedo-boat-destroyer". The Royal Navy, among others including the USN, discovered that these "TBDs" were effective torpedo-launching platforms and had far superior sea-keeping qualities than the small, low-freeboard torpedoboats.Battle Fleet (Fleet Flagship SMS Friedrich der Große, ADM Ingenohl)

Germany didn't buy that. The RMA continued to design torpedoboats that still looked like torpedoboats though these things tended to get bigger and bigger. The vessels that accompanied Hipper's squadron across the North Sea in 1914 included some of the largest in the High Seas Fleet inventory, the 1913-class "large torpedo boats" which were destroyers in all but name.

Eventually the reality that there is such a thing as too small and too cheap sunk in; the smaller German torpedo boats were just outclassed by British destroyers. By 1917 Germany was no longer building any of the older type; the destroyer had, as her name indicated, destroyed the torpedo boat.

The bulk of the capital ship strength of the High Seas Fleet was present but not engaged during this action, a total of 14 dreadnought battleships and 8 older pre-dreadnought battleships in three squadrons. Escorts included 2 armored cruisers, 7 light cruisers, and 56 destroyers.

Instead of listing the vessels and the capabilities I append the useful diagram courtesy of the good people at GHQ models (who produced a useful little summary of the Scarborough Raid we'll talk about in Sources):

To give you a sense of the overwhelming German superiority in numbers, here's the British forces from the same source:

Scary, innit? The German Navy should have kicked British ass like a crazy monkey.

The question this post will answer - I hope - is why didn't they?.

Anyway, the German forces shared a similar problem with the British - no overall commander.

The raiding force was under KADM (Rear Admiral) Franz Hipper, the main battle fleet was under command of ADM Friedrich von Ingenohl, the nominal commander of the High Seas Fleet. But operating under radio silence von Ingenohl was unable to direct Hipper and Hipper unable to inform his superior of his situation. So, effectively, the two forces were independent of one another.

The Sources: All the usual voluminous primary sources on both sides: ships' logs, war diaries, communications logs, orders, communiques and minutes, damage reports...the works.

If you want to take the time to do the original research the Imperial War Museum and the German Militärhistorisches Museum der Bundeswehr I highly recommend it. For this post I will try and provide some generally available (i.e. popular) published secondary source works as well as primary and secondary information available online to the English-speaking reader.

The British National Archives has an online library of its official documents from the 1914-1918 period. Well worth a perusal.

The Royal Navy has an official museum, as well as several specific locations (such as the old Portsmouth Dockyard) which tell individual parts of the story of the Senior Service, although, interestingly, a search of the RN Museum site on the words "Hartepool", Scarborough" and "Scarborough Raid" turned up absolutely nothing.

Hmmm.

I couldn't even find a similar resource for the former Kaiserliche Marine. If there is a "German Navy Museum" it is tucked away somewhere away from the Internet. The modern German Navy website has nothing remotely similar, being instead a glossy recruiting device including color pictures of cute red-headed German matelots looking as adorably devastating as a 12-inch broadside from a Derfflinger-class battlecruiser:

A section of the website called "WWW.WW1" or the Great War Period Documentary Archive (GWPDA) contains a trove of materials relating to the First World War at sea. A bit sparse to look at, but rich in information.

Another potential resource is the German Historical Museum, although, again, a search of key words relating to the action at 3.5 Degrees East brought no results.

The website War Times Journal has reprinted two portions of an English translation of ADM Reihard Scheer's 1920 work Deutschlands Hochseeflotte im Weltkrieg; Persönliche Erinnerungen ("Germany's High Seas Fleet in the World War; personal memories"). Worthwhile look of how the actions of 16 DEC 1914 appeared from the German side of the hill and at that time - the great secret of Room 40 was still locked in the Official Secrets Act.

Which brings us to one of the most critical parts of our story; the mysterious "Room 40" and the British cryptanalysis and codebreaking operation that set the clockwork in motion that almost resulted in a naval engagement at 3.5 Degrees East.

This piece of naval history has been the subject of several published works. Interestingly, there is little on-line that covers the subject exceptionally well. The Wikipedia entry is drawn largely from the published work of Patrick Beesly (1982) and, while neither badly written nor misinformed offers little that the reader couldn't get either from Beesly (1982) or Massie (2004).

However, several websites provide some juicy tidbits from the story Room 40.

The German Naval Warfare site contains a page offering several pieces of intel gathered by Room 40, including the page from the Signalbuch der Kaiserlichen Marine (SKM) taken from SMS Madgeburg early in 1914 that effectively started the entire British decryption program.

One of the pages from that codebook is inserted in this post above right.

British WW1 naval signals intelligence is a story fully as rich and fascinating as the "Ultra Secret" of WW2. It centers around the acquisition of three codes; the SKM, the Handelsschiffsverkehrsbuch (HVB) used (as the name implies) largely by German merchant marine but also to communicate with Imperial warships taken from the German steamer Hobart on 11 OCT and a diplomatic codebook, the Verkehrsbuch (VB) recovered on 30 NOV from the Channel where the commander of the torpedo boat S-119 had tossed it overboard as the ship foundered.

The story of the SKM is perhaps the most dramatic.

SMS Madgeburg ran aground scouting the island of Odensholm off the coast of Russian Estonia and in an ensuing clusterfuck - the commander tried to shatter her with explosives, the charges were set off too soon, and in the panic three copies of the codebook were either forgotten on-board or hastily hucked into the water. All three were grabbed up by the Russian Navy cruisers that arrived as the German-fire-drill was in progress.

Copy number 151 was the one passed to the British (the Russians kept the other two, the ones found in the water). The German Navy was using a fairly simple cipher as well as this code, so between the SKM, the HVB, and the VB the cipher was broken and the codebooks enabled British Naval Intelligence to read intercepted German wireless telegraphy (W/T) signals.

Here's the description of the SKM, from the Wiki entry:

"The SKM (sometimes abbreviated SB in German documents) was the code normally used during important actions by the German fleet. It was derived from the ordinary fleet signal books used by both British and German navies, which had thousands of predetermined instructions which could be represented by simple combinations of signal flags or lamp flashes for transmission between ships. There were 34,300 instructions each represented by a different group of three letters. A number of these reflected old-fashioned naval operations, and did not mention modern inventions such as aircraft. Ships were identified by a three letter grouping beginning with a Beta symbol. Messages not covered by the predetermined list could be spelled out using a substitution table for individual letters. The signals used four symbols not present in ordinary Morse code (given the names alpha beta gamma and rho), which caused some confusion until all those involved in interception learnt to recognise them and use a standardised way to write them."The ciphers would be changed from time to time, but the SKM itself was a ginormous volume and the Imperial Navy really didn't want to rewrite it.

That, and the smart guys in Berlin and Kiel didn't believe that the effete Brits had the mental throw-weight to break their code, anyway. Why go to all that trouble?

The officers of the Kaiser's Navy were the Smartest Guys in the Room, right?

I don't really have room for all of it here but as I mentioned, the story of Room 40 and the British cryptographers is a hell of a tale and well worth pursuing on its own.

Lastly, I found two very useful popular sources for the overall conduct of the war, the events of December 1914, and the vessels involved.

The first, and best, was Robert Massie's terrific 2004 work Castles of Steel. A large part of this post was taken directly from Massie's book which, along with being a first-rate source of information is thumpingly well-written. I can't recommend it highly enough; a superb work of popular history.

One caveat, however.

Anyone researching the naval war of 1914 will quickly find that the Royal Navy side of the issue is fairly sharply divided between partisans of the then-commander of the Grand Fleet, ADM Sir John Jellicoe, and the man who commanded the Battle Cruiser Fleet at that time, VADM David Beatty.

I won't go any further than that into the matter - tho we'll hear more about this later - but suffice to say that Massie is a "Jellicoe man". I believe that where he issues judgements against Beatty he is in the main well-supported by the facts. But he IS a Jellicoe partisan and his work must be read as such.

The other was a nice little volume from the Osprey people; British Battlecruiser vs. German Battlecruiser 1914-1916 (Stille, 2013). A bright, readable summary of the issues of naval tactics and warship design as they were embodied in the battle cruisers, and the strategies that meant that the two elements would collide and result in the deaths of thousands of sailors.

I should add that after reading the latter I ran across a nicely done 2010 paper by someone named Ott entitled Battlecruisers at Jutland: A Comparative Analysis of British and German Warship Design and its Impact on the Naval War that provides very similar analysis and conclusions as does the Stille work. Well played, Ott!

So, are we done here? Good.

Let's first look at what was happening in the North Sea in December, 1914, and why.

The Campaign: 1. The Imperial German Navy and the Struggle for the North Sea

The fundamental reason that the Royal Navy was out in the North Sea in December 1914 was a certain gentleman in Berlin who was officially known as

"His Imperial and Royal Majesty Wilhelm the Second, by the Grace of God, German Emperor and King of Prussia, Margrave of Brandenburg, Burgrave of Nuremberg, Count of Hohenzollern, Duke of Silesia and of the County of Glatz, Grand Duke of the Lower Rhine and of Posen, Duke in Saxony, of Angria, of Westphalia, of Pomerania and of Lunenburg, Duke of Schleswig, of Holstein and of Crossen, Duke of Magdeburg, of Bremen, of Guelderland and of Jülich, Cleves and Berg, Duke of the Wends and the Kashubians, of Lauenburg and of Mecklenburg, Landgrave of Hesse and in Thuringia, Margrave of Upper and Lower Lusatia, Prince of Orange, of Rugen, of East Friesland, of Paderborn and of Pyrmont, Prince of Halberstadt, of Münster, of Minden, of Osnabrück, of Hildesheim, of Verden, of Kammin, of Fulda, of Nassau and of Moers, Princely Count of Henneberg, Count of the Mark, of Ravensberg, of Hohenstein, of Tecklenburg and of Lingen, Count of Mansfeld, of Sigmaringen and of Veringen, Lord of Frankfurt."Kaiser Bill, as my great-uncle and his pals in the 42nd Division probably called him when they weren't calling him "that #!$%!#." He's important, and let's begin with him and his hard-on for battleships.

Prussia, Wilhelm's grandpappy's original dominion, had a navy as far back as 1701 (and the also-Hohenzollern-ruled state of Brandenburg earlier than that, but, whatev...) and the Preußische Marine was always kind of a Prussian in-joke, a good laugh for the potato-farmers of the East Prussian plain.

Prussia and its successors, first the "North German Confederation" and then Imperial Germany, had always been continental Powers, so until the late 19th Century the Prussian and German navy was ignored in peacetime and useless in wartime and most Prussians (and the other Germans) were just fine with that.

In particular the Prussian and later German Chancellor, Otto Bismarck, who considered the mightiest ocean not worth the bones of a single Pomeranian matelot and fought tirelessly against naval appropriations until the Emperor fired him in 1890. One of the main reasons is that Bismarck thought colonies and navies were worthless and his sovereign luuuurved them both.

That Imperial Germany had a genuine navy by 1914 was because Wilhelm II had a bizarre man-crush on navies, even more bizarre than the rest of his character which was a bit of a fright.

Here's what the historian Thomas Nipperdy had to say about him:

"...gifted, with a quick understanding, sometimes brilliant, with a taste for the modern,—technology, industry, science—but at the same time superficial, hasty, restless, unable to relax, without any deeper level of seriousness, without any desire for hard work or drive to see things through to the end, without any sense of sobriety, for balance and boundaries, or even for reality and real problems, uncontrollable and scarcely capable of learning from experience, desperate for applause and success, — as Bismarck said early on in his life, he wanted every day to be his birthday — romantic, sentimental and theatrical, unsure and arrogant, with an immeasurably exaggerated self-confidence and desire to show off..."This guy, who as you can imagine would have been kind of irking if he had been in charge of a Pizza Hut but was absolutely terrifying as the supreme War Leader of the mightiest state in Europe, also had an intense love of, and hatred for, England and, in particular, the Royal Navy.

In that peculiar mind the most important thing that he could do was build a navy of his own, like the Royal Navy...but better, and, in the end, capable of defeating that navy and proving to all the superiority of all things German and, in particular, His Imperial and Royal Majesty Wilhelm the Second.

Like anything else connected with absolute rulers Wilhelm's obsession attracted others with similar tastes wishing to remora on to his power. Among them was a Prussian sailor named Alfred Tirpitz who had never forgotten his experience as a young officer when, in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, he and his ship had spent the time tied to the wharf whilst the German armies romped through France winning military glory.

That wasn't gonna happen again if Tirpitz had anything to do about it.

The Emperor and men like Tirpitz, intent on seapower, crafted the instrument that became the Imperial German Navy built around the capital ships, the battleships and battlecruisers of the High Seas Fleet. There was only one problem.

Bismarck was right.

Germany needed a navy like a rhinoceros needs a pair of water wings.

The High Seas Fleet did nothing but force Germany into a naval race and naval stand-off with Britain, because while a navy was an affectation for Wilhelm II it was a necessity for Great Britain.

2. The Naval Strategies of 1914, Simplified

Great Britain has depended on naval power almost since it was united as a nation, even before it's sprawling Victorian empire. An island nation nearly always develops seapower both for defending the island itself and for protecting the trading vessels it needs to ship its products out and its purchases in.

Typically - that is, from the late 16th to the early 20th centuries - a British European campaign involved a large maritime force blockading enemy ports and strangling enemy sea-lanes and something ranging from small to miniscule field army involved in caprioling about the periphery of continental Europe; the Low Countries and the Rhineland in the 17th and 18th, Spain and Portugal (and the Crimea) in the 19th.

Although 1914 marked the first use of a "big" army in war Britain had the same basic plans for her war at sea.

Basically, Great Britain couldn't "win" the war at sea; no naval force could push the German Army out of Belgium (Britain's casus belli) or France.

A naval blockade would have the gradual effect of weakening German war production and starving individual Germans. Curiously, the single most critical material cut off by the blockade was nitrate fertilizer, then largely produced from the bird-islands off the Andean coast of South America. Without imported bird shit German agriculture cratered. With the loss of farm products from the U.S. this led to a lot of hunger and suffering.

As predicted, this punished the hell out of the Central Powers.

But...thought the blockade might not "win", if the Royal Navy screwed up it could lose the war for Britain at sea.

Here's how.

Germany needed to blockade Britain, too, and that meant getting her navy out into the Channel, the North Sea, and the Atlantic. That meant that she had to hammer the British fleet out of the way, or at least that was the thinking in Berlin in 1914. The idea that submarines - small, slow, and fragile - might threaten the scepter'd isle seemed risible at the time.

Instead beating Britain meant beating her fleet, sinking the battleships that were the steel castles fortifying Britain's coasts and protecting her lifelines, the merchant vessels that supplied her factories and people.

So long as the Grand Fleet bottled up the North Sea and the Channel squadrons the Channel - so long as the High Seas Fleet couldn't break through, couldn't destroy these Royal Navy units - that wouldn't happen.

Just so you know, traditionally Britain had used what's called a "close blockade" against continental enemies. That is, British warships rode just off the hostile shore, within sight of the enemy ports. There they ran down enemy merchant ships and engaged any enemy naval vessels that came out to fight.

It worked for Nelson, and for the Royal Navy if it worked for Nelson it worked for them.So.

So it took over 100 years for the RN to realize that 20th Century threats like steam torpedoes, contact mines, and powered steel-hulled torpedo boats and destroyers presented the sort of threat to British battleships that Napoleon's three-deckers never did.

In 1913 the RN officially abandoned the grand tactic of "close blockade" for the distant picket line scheme implemented when war broke out in 1914. This meant that those battleships were still waiting, but now at the choke-points of the North Sea far from the German naval bases of Kiel and Heligoland.

For Britain, the most critical element of naval strategy was not losing her fleet.

So long as the Royal Navy possessed enough fighting power to keep the German Navy confined to the North Sea, so long as the Grand Fleet existed and continued to represent a dire threat to German seapower Britain could keep fighting and, hopefully, find a solution to the land-war problem.

For Germany, the most critical element of her strategy was defeating - or finding a way around - the Royal Navy.

You see the difference?

Germany had to win.

Britain just had not to lose.

3. When Enemies Don't Cooperate...

By the autumn of 1914 the Germany naval command realized it had a problem.

Since the formation of the High Seas Fleet in the 1880s German naval strategy had relied on the Royal Navy's "close blockade".

With the British capital ships close to the North German shore the High Seas Fleet - and especially swarms of torpedo boats and minelaying cruisers - could harass the British fleet until the German battleships could sortie and savage the remainder. Damaged German dreadnoughts could quickly retire to their harbors, while British cripples would have to risk the waters of the North Sea, German U-boats, mines, and torpedo craft.

August 1914 came, however, and not a British battlewagon was to be seen. German steamers were being pulled over far in the north, from the remote Grand Fleet base at Scapa Flow in high Scotland, and in the Western Approaches.

German trade was being strangled, German farmers losing crops, German soldiers going hungry.

But without a close blockade, what was the Kaiserliche Marine to do? How could the High Seas Fleet break the power of the Royal Navy if the Royal Navy wouldn't oblige it by coming out to fight - with the added restriction of following the Emperor's dictate not to risk German capital ships in a head-to-head clash with the Grand Fleet?

Although the All-Highest had forbidden the High Seas Fleet to seek out its enemy he had not ruled out any sort of offensive action. So the leadership of the Imperial Navy - Navy Chief of Staff ADM Hugo von Pohl, ADM Georg von Müller, the head of the Marine-Kabinett (a sort of Naval Secretariat that served as a sort of G-1 (personnel) and G-3 (operations) for the Emperor), and ADM von Ingenohl - came up with an idea in late October, 1914.

These jokers hoped to use a combination of mines, U-boats, and surface actions off the east coast of England to lure out pieces of the Grand Fleet in hopes of defeating these detachments and evening the odds. The plan was that Hipper's Scouting Group would dash across the North Sea and bombard coastal towns along the northeast coast of England; meanwhile light cruisers would lay mines and U-boats would lurk along the coastline, in both cases hoping to catch British warships responding to the initial attack.

The plan was a classic "baited ambush"; cause a ruckus then bushwhack the reaction force as it hurries towards the commotion.

The first of these raids took place 3 NOV 1914. The I. Aufklärungsgruppe sallied out of the Jade River on the afternoon of 2 NOV. Two squadrons (probably First and Third; I can't imagine why Ingenohl would bother with the old pre-dreadnoughts of the Second if he didn't have to...) of the High Seas Fleet sortied out of Wilhlemshaven later in the day to support the raiders.

The immediate objective was to lay mines off the the Norfolk port towns of Yarmouth and Lowestoft and shell Yarmouth as well. The overall grand tactical plan was that the raiders would lure the responding Grand Fleet element - presumably VADM Beatty's battlecruisers plus whatever Grand Fleet squadron and light units from the eastern Channel Fleet at Harwich were backing him up - south and eastwards onto the U-boats and the minefields. And when these lurking weapons had crippled the British squadron the great pale-gray leviathans would loom out of the sea-smoke.

There the arrogant British would be destroyed.

That was the plan, but in fact the actual action turned out to be something of a bust.

For one thing, the Admiralty never responded; no elements of the Grand Fleet so much as raised steam until the raiding forces were headed back to their moorings.

For another, the damage done to both sides was minimal and fairly even. A small RN force posted at Yarmouth lost a submarine to one of Stralsund's mines but the armored cruiser SMS Yorck blundered into a German minefield off Wilhelmshaven and sank of 4 NOV.

Hipper's force didn't even do any real damage to Yarmouth; most of the Scouting Group's shells landed on the beach nearby.

The results, however, seemed to prove that the idea was sound. All the German players, especially KADM Hipper (who was violently disappointed by the results of the Yarmouth Raid), wanted to try the trick again. This time, however, the targets would be further north in the county of Yorkshire; Whitby, Scarborough, and Hartepool.

Of the three Yorkshire Riviera towns only Hartepool was a fairly "legitimate" target. Its steel-, dock-, and gasworks served a war-industrial function and it had an actual coastal defence garrison manning two shore batteries and three 6-inch cannon. The other two towns (if they may be so termed; Whitby in 1914 probably had a total population of no more than 2,000 to 3,000 people) were of no real military value.

Whitby was basically a big fishing village.

Scarborough was something of the Cancun of coastal Yorkshire, the seaside playground of the North complete with an opulent resort hotel and the usual Victorian diversions.

The raid wasn't really about damaging the British war effort, however; it was about mousetrapping the Royal Navy.

4. The Scarborough Raid

The actual conduct of the coastal raid is fairly well detailed in the Wiki entry, and I won't cover it exhaustively here. As an operation it ran on rails. The raiding force left early in the morning of 15 DEC arrived off the Yorkshire coast early on 16 DEC; the only hitch was the weather which had deteriorated badly overnight, forcing Hipper to order his escorting light cruisers and torpedo boats back to port - only SMS Kolberg remained with the battlecruisers in order to carry out the minelaying part of the mission.

SMS Seydlitz, SMS Blücher and SMS Moltke shelled Hartlepool between 8 and 9am; SMS Derfflinger and SMS Von der Tann hit Scarborough between 8 and 9:00 and then sailed north and hit Whitby some time probably between 9 and 9:30.

While the big ships were shelling SMS Kolberg laid mines stretching about 10 miles east of Flamborough Head.

The British defenders did what they could in response. Four destroyers of the Hartepool stachment - HMS Doon, HMS Test, HMS Waveney and HMS Moy attempted to attack the three German warships off Hartepool but, outgunned and outranged withdrew after a token effort. HMS Patrol was the only cruiser in Hartepool harbor with steam up, but in putting out towards the harbor channel was crippled. The submarine C9 actually did clear the breakwater but was forced to dive and unable to catch the raiding force submerged.

The Durham Light Infantry did rather better, gunfire from the Lighthouse Battery in particular doing damage to SMS Blücher (hit six times, two of her secondary 6" cannon were disabled and one of her main guns damaged with 9 KIA and another 3 wounded).

The British gunners themselves lost 6 killed, 11 wounded. The Heugh Battery website says that the battery would have been hammered harder except "...the Germans were using standard anti-ship ammunition with time delay fuses which bounced off the gun aprons to explode behind the batteries..."

As it always seems customary in war, the unarmed suffered and died more than anyone in uniform. Somewhere north of 80 women, children, and civilian men were killed at Hartepool from the more than 1,100 German shells of all calibers fired into the city. Over 400 were wounded. Another 17 civilians were killed at Scarborough and two at Whitby, with another hundred or so wounded.

By about 10am the raiding force had rejoined and were heading back east towards what they assumed was a link-up with the High Seas Fleet and, hopefully, an ambush of a Royal Navy rushing to the rescue.

They couldn't have been more wrong, and that's where we'll begin our story of what should have been a crushing German naval victory averted by good intelligence and bad decisions.

The Engagement:

To tell the story of the battle that should have been we have to back up two days, to about seven in the evening Monday, 14 DEC, when Sir Arthur Wilson met with Winston Churchill (the First Sea Lord) and ADM Henry Oliver, the Chief of the Admiralty War Staff.

Wilson briefed his superiors on the signals intelligence that Room 40 had gathered. German radio messages indicated that the High Seas Fleet's scouting groups were going to sortie again. As we know, this was true.

But Wilson also added a conclusion that the sigint people had reached from a absence of wireless chatter that the battleship units of the Hochseeflotte were not going to support Hipper's group. Based on this information Churchill and Oliver agreed with Wilson that the British response should be less than maximal. A single Battle Squadron would be sent along with Beatty's battlecruisers to trap the raiders.

I don't know, and my sources don't explain, why Room 40 intercepted no transmissions from the main body of the High Seas Fleet. But Massie (2004) may provide a clue where he discusses German plans for the raid:

"The kaiser had forbidden Ingenohl to risk a major fleet action, and the admiral had no intention of disopbeying...Ingenohl was stretching his orders and he was careful to protect himself in a manner common in Imperial Germany: he did not tell the kaiser what he was going to do." (emphasis mine; Massie, 2004, p. 328)It may be that this discretion extended to Ingenohl's fleet wireless discipline as well.

A radio message not sent was a message not recorded in a signal log or an order book. A message not recorded could be denied, or, at least, not provide a source of imperial suspicion and abrogation.

The Admiralty telegraphed orders to ADM Jellicoe at Scapa Flow: "Send at once, leaving tonight, the Battle Cruiser Squadron and Light Cruiser Squadron supported by a Battle Squadron, preferably the Second. At daylight on Wednesday they should be at some point where they can make sure of intercepting the enemy during his return."Jellicoe obeyed with concern and some annoyance.

At no time during the whole of WW1 were the High Seas and Grand Fleets so evenly matched as November and December of 1914.

HMS Audacious, a new King George V-class battleship, had been lost to a mine off Ireland in late October. Four other battleships were refitting, their engine machinery strained to breakdown by the constant patrolling of the North Sea. Three of Beatty's battlecruisers had been dispatched to the South Atlantic to hunt down the German Asiatic Squadron.

The British battlecruisers were particularly vulnerable, with four British ships matched against four German, five if the Blücher was included.

The German naval staff knew they might never have a better time to try and cut down the odds. But there was this problem; the Emperor would not risk his fleet. If the High Seas Fleet was going to seize the opportunity it would have to be through a loophole in the Imperial edict.

Massie (2004) explains:

"The kaiser had given the Commander-in-Chief a command to hold back the fleet in order to control the Baltic and permit the release of coast defense troops to alleviate the manpower demands of the army. But William had left a loophole: "This does not, however, prevent favorable opportunities being used to damage the enemy...There is nothing to be said against an attempt of the battle cruisers in the North Sea to damage the enemy."There it was. That was the loophole.

The Scouting Group would be the bait, the mines and U-boats the trap.

The High Seas Fleet would simply provide insurance in case of...something.

The British squadrons weighed anchor separately; Beatty's battle cruisers from Cromarty Firth at 6am, Warrender's battle squadron from Scapa at 5:30. The weather was bad; "...a very heavy sea which caused even Lion to roll in a disquieting manner." (Massie, 2004, p. 335). The two British fleet units met off Moray Firth at 11am, 15 DEC amd proceeded south-southeast.

At this point either the sigint had not revealed the German objective or Room 40 had not passed this information on to the fleet. Warrender's flag signals are recorded as informing Beatty "I think raid probably Harwich or Humber...", both well south of the actual targets on the central Yorkshire coastline.

From the rendezvous point the combined British force headed southeast to the location Jellicoe had chosen as the intercept point (and, supposedly, a meetup with light forces from the Channel fleet); about 100 miles east-southeast of Scarborough and 180 miles north-northwest of the Heligoland coast of Germany. The big ships moved heavily in the rough seas, and in the overcast night visibility ranged from poor to virtually nil.

So. Here's our first position map; the three main forces at about 4:00am.

(I apologize for the quality of the map; I had to use what I could find on the Web, so my base map wasn't great. If you enlarge the picture you'll get a better view.)

Anyway, you can see the British force is still moving southeast, roughly 50 to 60 nautical miles northwest of their planned intercept point. The German 1st Scouting Group is south and west of them moving west, the main body of the High Seas Fleet roughly 150 nautical miles east of the British main body.

Both the British and the German battle fleet have light forces screening them; the British to the southwest, southeast and east, the German battle fleet to the west. Hipper's light ships are taking a pounding in the heavy seas; some have already lost contact, including the S-33 (remember, Hipper orders them to turn east about two hours later...) but the weather is actually breaking up. As daylight approached the seas began to drop and the sky clear, at least clear for a North Sea December

The little S-33 began the day's adventure with a frightening encounter.

The torpedo boat was separated from the rest of 1st Scouting Group before midnight. She tried to raise another German vessel in the raiding force and was told to shut the hell up - her radio transmissions were compromising security of the group.

Lost and alone, S-33 reversed course and headed for home. At 4:00am she blundered into four British destroyers steaming southeast (presumably part of the Beatty/Warrender force's escorts).

The German captain turned onto a parallel course and spent what must have been a hell of a nervous twenty minutes cruising along trying to look British before S-33 was able to slip away. She broke radio silence again to inform KADM Hipper that the British - at least some of their light forces - were out in the North Sea that night.

Still, there's no reason yet for a German naval officer to get his panties in a twist. Yes, there were British ships abroad in the night. But so far there was no sign of enemy capital ships and, surely, the High Seas Fleet had gunpower enough to deal with any stray British destroyer flotillas.

All the vessels maintained their courses and speeds.

Situation: 4:00am - 9:00am

This condition continued until about 5:30am.

The disposition of the various forces were as shown below:

The Second Battle Squadron still steamed southeast, the center of the formation. Beatty's four battlecruisers formed the point element five miles southeast of the six battleships. The four light cruisers formed the starboard-side screen, steaming in line-ahead about five miles southwest, the four armored cruisers about a mile to port (northeast) with Beatty's seven destroyers another nine miles beyond that.

It was these destroyers who made contact with the German main body screen.

HMS Lynx, leading the group, ran across the large torpedo boat V-155. As you can see from the battle map, V-155 turned and ran north for the next half hour, trading gunfire with the British flotilla in pursuit.

As would reoccur again and again in the North Sea between that night and the battle of Jutland two year later German gunnery was both more rapid and more accurate. Two hits smashed Lynx's propeller or rudder or both and she veered hard to port, the entire British line swinging southwest with her. Ten minutes later V-155 holed HMS Ambuscade below the waterline and she staggered away to starboard - west - leaving her six sisters behind.

The six survivors weren't enjoying themselves. The light cruiser SMS Hamburg with two escorting torpedo boats arrived in response to V-155's frantic messages for help and smashed HMS Hardy with searchlight-directed gunfire. Hardy's bridge was wrecked and her steering gear disabled, she was afire, and her captain was conning the destroyer by shouting down the engine room hatch.

The little ship wasn't going without a fight, however; her guns blasted Hamburg's searchlight platform. She also fired a torpedo; Hamburg's lookouts spotted the wake and the cruiser turned away, broadcasting a warning at about 6am that British torpedoes were in the water.

The warning was superfluous; the High Seas Fleet was turning away. Massie (2004) describes what had happened:

"The presence of British destroyers...had been reported to Admiral von Ingenohl as early as 4:20 a.m....The report worried Ingenohl. Like Warrender, the German admiral feared a destroyer torpedo attack on his battleships, especially a night torpedo attack. An hour later, at 5:23 a.m., when news of the destroyer action reached his flagship...the admiral's apprehension markedly increased. Already he had stretched his instructions...now here he was in the middle of the North Sea in the darkness of a December night, seeing the flashes of guns on the horizon...a British torpedo in the water, his screen retreating, the British pursuing - and an hour still remaining before daybreak." (p. 338)At 5:30 ADM Ingenohl ordered the High Seas Fleet to reverse course.

Massie (2004) is merciless about this; he states flatly that Ingenohl's "courage failed him". I cannot be quite as condemnatory. To me, Ingenohl's courage was suspect when he allowed this entire plan to proceed knowing that he was in violation of his Supreme Commander's order - regardless of the wisdom of that order - and that if placed in the exact position he was in before dawn on 16 DEC he would have to choose either to risk all or abandon some of those in his charge.

But the decision that the commander of the High Seas Fleet made then, in the pre-dawn twilight of the bridge of the Friedrich der Große, well...it seems to me a fine line between cowardice and common sense.

Had the entire Grand Fleet been at sea? Had the German battleships suddenly stumbled into a wild dawn melee with a swarm of British destroyers backed by the massed heavy guns of the full strength of the Royal navy..?

I cannot simply condemn Ingenohl out of hand for that.

For approving the mission as planned? Yes.

For making the choice he made that morning?

No.

So the High Seas Fleet turned away.

"For forty minutes the two fleets were steaming on almost parallel courses (southeast), the British destroyers south of the Germans, the British battleships and battlecruisers to the southwest. The screens continued to brush against each other. At 6:15 (the cruiser) Roon saw and was seen by Lynx and Unity...Earlier, Ingenohl had received Hamburg's report of her encounter with Hardy. Now, from Roon, he heard about another destroyer contact. Confirmed in his belief that the sea was swarming with enemies, Ingenohl at 6:20 a.m. singaled a further turn to port and at high speed made directly for Germany." (Massie, 2004, p. 340)The British destroyer and German cruiser-torpedo boat screens continued to clash for the next hour and a half, first one way then another. Finally at about 8:00, as the day was breaking the two screens broke contact, the Germans heading east to cover the retreat of the High Seas Fleet, the British west to rejoin the main body of the capital ships.

By this time the wind and dropped and the sea calmed; the morning was as clear as one could hope for in the North Sea in December. Warrender and Beatty's force had arrived near the prearranged meetup/intercept point (the Channel forces had been recalled by the Admiralty without informing either commander, an incident that caused some minor confusion and irritation, especially to Beatty. Warrender had commandeered his destroyers and he had expected to be reinforced from the Channel Fleet).

Radio reports from the British destroyers had been confusing and somewhat garbled, and the Royal Navy battleships and battlecruisers spent the next hour loafing about the meeting point trying to do something without really knowing who or where they needed to do it to; the section of the main battlemap below gives some idea of how random the British movements were:

The black trackline is 2nd Battle Squadron, the blue is the Battle Cruiser Fleet; light units are dashed lines in blue or black depending on which major element they were attached to.

It's like a bad wiring diagram, isn't it?

Anyway, the other shoe dropped at 8:42. HMS Lion picked up a signal from HMS Patrol announcing that she was engaging two German battlecruisers.

A few minutes later a signal from the Admiralty in London announced that Scarborough was being shelled.

Situation: 9:00am - 3:30pm For the approximate positions of the various forces at about 9:00am, see below:

The British battle squadrons were steaming northwest, the battlecruisers and light cruisers ahead and slightly north of the battleships and armored cruisers. Between 10 and 10:30am the two forces diverged around a nasty shallow portion of the Dogger Bank (the "southwest patch") on the battle map below. Beatty and the battlecruisers went north of the patch, Warrender's battleships to the south.

This led the British forces towards a large gap in the minefields that lay off the Yorkshire coast north and south of the Scarborough-Whitby coastline. A roughly twenty-mile wide gap opened due east of the German targets; this would be the most likely route for the retreating German battlecruisers. Second Battle Squadron was headed for the south side of this lane, while the Battle Cruiser Fleet was headed for the north. 1st Scouting Group was steaming east for the exit at top speed.

Here's the positions of the forces a bit later, around 12:30 to give you an idea:

First the Kaiser's order, the dark, and the British destroyers had help save the Royal Navy's capital ships. Now the weather and a series of poor decisions intervened to help save the German battlecruisers.

In fifteen minutes - between 11 and 11:15 - rain squalls and heavy mists blew in from the northwest, just another North Sea winter storm. Visibility dropped to less than a mile in the worst of the squalls, forcing the big ships to reduce speed and tormenting the smaller ones.

Still; at about 11:25 HMS Southampton sighted SMS Stralsund and eight torpedo boats steaming directly east towards her.

Southhampton exchanged fire with Stralsund, and the German squadron turned south trading shots with the British cruiser. The British light cruiser force closed up to engage and as they did Southampton, the leading ship, saw two more German cruisers (these were Strassburg and Graudenz and their escorts - the remainder of the light vessels Hipper had ordered to return to port earlier) approaching from the west.

Here the officer commanding the British light cruisers, RADM William Goodenough, made an error. He had directed his signals officer to radio VADM Beatty when the Southampton first engaged Stralsund

He did not inform his superior of the additional German cruisers.

VADM Beatty watched as his screening cruisers veered away to pursue - as he knew it - a single enemy light cruiser and a handful of torpedo boats. Worried about blundering into the German battlecruisers without a scouting screen, he ordered the last cruisers to leave his battlecruisers - HMS Nottingham and HMS Falmouth - to resume their station as escorts.

Beatty's signals officer - his "flag Lieutenant" LT Ralph Seymour - then compounded the error. Rather than signalling the two cruisers his blinker-light signal simply read "light cruiser". This was passed on to RADM Goodenough as a recall for the entire squadron at about 11:50 a.m. Goodenough ordered his unit to cease pursuit at about 11:55.

Too late, VADM Beatty was furious that his subordinate would turn away from a fight and bitched out his cruiser commander in a series of signals that the entire squadron could read, heedless of the fact that it was his own signals officer whose sloppiness had largely caused the break in contact.

Meanwhile the lucky Stralsund was being saved from destruction yet again, this time from Warrender's battleships.

At about 12:15 the German cruiser sighted the 2nd Battle Squadron and was, in turn, sighted by the leading ship in the starboard (northern) column, HMS Orion. VADM Warrender and his staff on King George V was socked in by a rain squall and could not see the Germans.

Orion ran up "enemy in sight" and her captain ordered her main battery trained onto the Stralsund, the leading German cruiser. He pleaded with the commander of his division, RADM Arbuthnot, embarked on Orion, for permission to open fire.

Arbuthnot (that's him over on the left) refused; it was his commander. Warrender's, place to give that order.

But Warrender never did give the order, Orion did not fire, and the German cruisers and torpedo boats easily evaded the slower British armored cruisers Warrender finally did send out to chase down the German lights. The Germans disappeared into the mist and rain.

At about this point VADM Beatty made a bad decision.

His forces were headed for the east edge of the minefield gap. Massie (2004) says:

"He expected to arrived around 12:30pm...and begin patrolling back and forth. Had he followed this plan, only unimaginably bad weather could have prevented him from sighting the German battle cruisers as they emerged from the gap around 1:00p.m."(p. 349)But Beatty was fidgety - he was always fidgety - and he was worried what might happen if Hipper's ships were headed towards the south side of the gap. He decided to turn back east. When he did so, at 12:30 p.m., Hipper's group was only about twelve miles to the west.

The Battle Cruiser Fleet steamed due east for 45 minutes, then north for another 40 minutes, then east again, then southeast. He found nothing.

Warrender's battleships had no better luck. They arrived at the southern minefield gap at about 1 p.m., quartered the area for about 25 minutes, then turned north.

First Scouting Group, meanwhile, had reached the eastern end of the gap at about 12:45 and turned hard to the north. Warrender's ships were close; the cruiser Kolberg was limping behind , damaged by the heavy seas, and was close enough to see Warrender's force's funnel smoke about 1 p.m.

The British forces continued to pursue until about 2:30 p.m. Here's a piece of the battlemap that gives you an idea of their wanderings:

At this time the Admiralty passed along a signal intercept giving the position of the High Seas Fleet as in the eastern North Sea. This was interpreted wrongly as a transmission from the German main battle fleet emerging from rather than returning to its harbor. The British called off the chase at about 3:30 p.m.

I should note here that Hipper's battlecruisers had more then one stroke of luck. When his light cruisers first encountered the British at around 11:30 the Konteradmiral's instinct was to back up his escorts and he sped eastwards at 23 knots.

Before he could collide with the British, however, Stralsund radioed that she had sighted enemy battleships. Hipper was neither a coward nor a fool; he continued east until his light cruisers radioed that they had evaded the British force. The scouting group commander then felt free to turn away, running in a wide loop to the north of the British forces. Here's the full battlemap showing the full scope of the action west of 4 Degrees East; note Hipper's movements in a wide arc to the north:

By 7:30 am the following day, 17 DEC, the last German vessel anchored in the Jade.

The Outcome: Minor German tactical victory

The Impact: The greatest impact of the actual raid was emotional. The dead of Scarborough, Hartepool, and Whitby were the first English people killed on their own soil by foreign enemies for some 200 years. British propaganda made great play about the deaths of innocents. "Remember Scarborough" - Whitby was too puny and Hartepool, perhaps, too grimy and, after all, a legitimate target - became a slogan for recruiters and war-fund drives.

The public was enraged at the German attacks but not pleased with the Royal Navy, either. Most of the RN didn't understand how lucky they were in that; the public didn't know about the Room 40 intercepts, or that it might have been possible to intercept the German raiders before they reached their targets. Had this information been public at the time the furor might have been insurmountable, a testimony to the later observation about the necessity of a "bodyguard of lies" for truths such as the Navy's intelligence program.

Within the Royal Navy Beatty blamed Goodenough for his bad decision but passed over his own signal officer's mistake; he would pay for this when Seymour would make more critical errors at both Dogger Bank in 1915 and Jutland in 1916. Arbuthnot was never censured for his hesitation, Warrender retired for health reasons in 1915. Beatty remained a popular hero and untouchable within the Navy.

Furious at not ensnaring Hipper's battlecruisers the British never suspected how close they had come to a disaster of their own; not until much later in the war did the Royal Navy suspect how close the twenty-two battleships of the High Seas Fleet had been to their ten capital ships, how thin the margin of their own survival had been.

In general the German public considered the Raid a great success. The haughty British had received a taste of war, and the Imperial Navy had swaggered across the North Sea and back with impunity.

Inside that Navy, however, many officers were not satisfied. The old doyenne of the Kaiserliche Marine, ADM Tirpitz, VADM Scheer, and Hipper himself considered that Ingenohl's retreat had thrown away a mighty opportunity to smash an arm of the Grand Fleet. Even the Emperor lectured his commander. "The effort to preserve the fleet..." the All-Highest prosed to ADM Ingenohl "...must under no circumstances be carried so far that favorable prospects of a success are missed owing to possible losses." (Massie, p. 359-360)

Ingenohl remained in command. The Berliner Borzeitung claimed "...the bombardment possibly heralds greater events to come." (Massie, 2004, p. 359)

No more coastal raids were ever carried out.

What might Have Happened?

I believe that had ADM Ingenohl held his course a general engagement between the High Sea Fleet and the British Battle Cruiser Fleet and 2nd Battle Squadron of the Grand Fleet would have taken place around dawn on 16 DEC 1914. While it is difficult to predict the fates of individuals and ships the weight of metal was so overwhelmingly in favor of the German force that it is difficult to believe that either of the British units would have escaped without significant loss, especially from the Battle Cruiser Fleet.

Why?

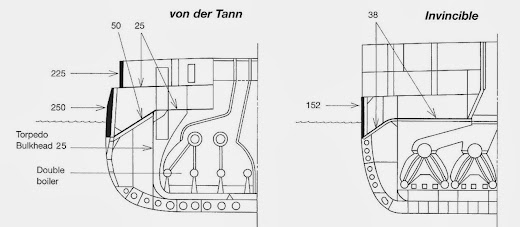

1. Armor Protection and Ship Type

The conventional "story" is that the British battlecruisers were disastrously underarmored; that Fisher's "speed is armor" philosophy led to a class of vessels without enough armor to protect themselves and as a result three were lost at Jutland along with almost every man in their crews, over 3,000 lives.

It is true that the battlecruiser was a flawed concept. Constructing a large, battleship-like, vessel, armed with battleship-caliber cannons, with the intent of then keeping this vessel out of battleship combat was a fool's notion. Even by WW1 I think this was being realized; you only have to look at the so-called "fast battleships" of the mid-war years, the Queen Elizabeth-class in Britain and the Bayern-class in Germany. These ships had a battlecruiser's speed but without the reduction in armor, armament, or internal protection.

How important was this? Look at the record of the two types at Jutland.

The battleships of the 5th Battle Squadron followed the battle cruisers. HMS Malaya was hit seven times, including one directly on top of her "X" Turret, Warspite 13 times, Barham six times. None of these hit resulted in significant damage.

Three British battlecruisers; Invincible, Indefatigable, and Queen Mary, were all sunk by gunfire at Jutland, at least two of them to fewer than 5 hits from heavy cannon rounds.

2. Ammo Handling and Propellant Type

But I think the the real problem went beyond just armoring; indeed, German battlecruisers proved much better-designed and better-armored but could still be holed by 11-inch and larger shells. Lützow was lost at Jutland and Seydlitz suffered tremendous damage there and at Dogger Bank, as well. Derfflinger took a hell of a hammering at Jutland and survived.

In fact, I believe that in December 1914 the propellant characteristics and shell handling procedures of the RN battleships and, especially, battlecruisers were dangerously inadequate. This is well discussed in Ott (2010) as well as Stille (2013), and I will try and summarize their work here.

The British and German navies both used a nitrocellulose-based propellant. The British version was known as cordite and came in the form of cords or sticks, like some sort of explosive Slim Jim.

The British also used a form of naval gun breech that allowed the propellant charges to be stored in cloth - usually silk - bags. These bags were kept inside metal containers in the magazines to help prevent flash fire. Prior to sending the propellant and igniters up the shell hoists to the turret the bags had to be taken out of the metal boxes and the igniters stripped out of their paper containers.

But this took time, and the British gun crews were drilled that rate of fire was the most critical part of naval gunnery. The ammo handlers therefore commonly stripped the propellant out of the containers and even stacked them outside the doors to the magazines. Doors were propped open and flashtight shutters either opened or not installed around the hoists.

The British cordite propellant also had a much faster burn rate than the German propellant. German propellant burned; cordite exploded.

3. Gunnery

German naval gunnery was consistently better throughout WW1. Just an example: at Jutland the British Battle Cruiser Fleet fired a total of 1,842 main gun rounds at their German targets for a total of 37 hits - a success rate of 2.01%. If you subtract the performance of the 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron (fresh from gunnery exercises at Scapa Flow) this drops to 1.43% - 21 hits for 1,469 rounds fired.

The 5th Battle Squadron of the Grand Fleet fired 1,099 rounds and scored 29 hits; 2.64% - if you add that to the battle cruisers' total you get an overall British gunnery accuracy of 2.24%.

During that time Hipper's I. Aufklärungsgruppe battlecruisers fired 1,670 rounds and scored 65 hits, 3.89 percent, or 1.7 times the British hit ratio.

German capital ships proved consistently quicker to establish the correct range to their targets and better at hitting those targets consistently, despite not using a central fire direction control system. At Dogger Bank the three battlecruisers and the armored cruiser Blücher of the 1st Scouting Group scored 22 hits on the four British battlecruisers. Aside from the hits that sank Blücher the Battle Cruiser Fleet put only six other rounds on target.

Combine all these factors:

The lack of protection to the British battle cruisers, poor ammunition handling procedures, highly combustible propellants, more accurate German gunnery, and the overwhelming advantage in numbers (22 battleships against 6 and the evenly matched battlecruiser numbers) and it is hard not to imagine that the High Seas Fleet might have won a smashing victory that day.

But...there was no battle.

What about the other counterfactual? What if Beatty had held his course and met Hipper's squadron emerging from the minefield gap?

Even assuming that something like Jutland happens and the German battlecruisers destroy, say, New Zealand and Queen Mary at the cost of Blücher badly wrecked, could Beatty have held onto the 1st Scouting Group long enough to let the 2nd Battle Squadron come up and pile on?

Remember, the Orions and KGVs were only 21 knot battleships. Assuming that British gunnery was no better in December 1914 than it was in 1916 I have to suspect that Hipper's big ships would have put the hammer down and escaped - probably losing the poor armored cruiser as they did at the real Dogger Bank.

Regardless of which example we take, a combination of poor planning, faulty decision-making, and bad luck combined to prevent the German fleet from trapping the British force, and then the British from trapping the German battle cruisers. And, most importantly, the Grand Fleet, and the Royal Navy forces ringing the North Sea, remained in place, dangerous as ever, and Germany's strategic position remained unchanged.

We know the rest; the failure of the High Seas Fleet to change the naval balance, the turn to the submarines, the "unrestricted" U-boot campaign that helped bring the United States into the war and help bring about the defeat of Germany and the Central Powers.

It is difficult now to say whether a smashing German naval victory at Dogger Bank in December 1914 would have turned the tide of the Great War.

But it might have nudged the flow sideways a bit.

We will never know.

What this non-battle reminds me is how often the affairs of men and states turn on the acts of one individual.

Had Ingenohl kept his course another half hour...had Beatty not turned east...had Jellicoe insisted on sortieing the entire Grand Fleet...had Goodenough signalled his contact with Hipper's entire cruiser screen, and had Seymour been better at his job...what might have happened instead of what did, fleets and squadrons passing in the cold rain and the mist, searching fruitlessly the gray waters of the restless sea.

Touchline Tattles: As is often the case in war, even the humorous tales to emerge from the events of 16 DEC are a grim sort of humor.

After the bombardment a coronor's inquest was held in Scarborough on Friday, 18 DEC, as is required whenever a British subject dies suspiciously or by violence. The Scarborough newspapers reported that :

"Mr Plummer Yoeman, Chairman of the Jury, stated "it was a murderous attack which caused all these deaths, a murderous attack on an unfortified town, and all the world should know".and asked the coroner if the jury could not bring in a finding of murder.

The coroner

"replied that if the jury returned a verdict of murder, he 'would have to go through the formality of binding the police over to prosecute someone'. The persons responsible, he pointed out, were the officers of the German ships, and, as the jury was bound to recognize, these persons were unavailable. Frustrated, the prosecutors terminated the proceedings." (Massie, 2004, p. 327)Supposedly the "Sandside Mission for Seamen" kept a parrot; I have no idea why other than perhaps the notion that parrots and sailors went together. The story goes that Pol Parrot was a talking bird and jabbered away volubly until the German shells started landing.

After that it never spoke again - perhaps Scarborough's first victim of shellshock.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Great work as usual Chief.

ReplyDeleteI am even softer on Ingenohl than you. Recall that the order to turn around was *before* the raid on the ports.

As soon as the guns started popping in the middle of the North Sea, the original "mouse trap" game was over.

It meant that the Royal Navy would not react by sending a fragment of their forces to chase the raiding ships. In fact, it suggested that the deployment of the Royal Navy was not at all as they had hoped (and that the Grand Fleet might already be in the neighborhood given the clashing screens, which indeed some portion of it was)

Given the complete failure of the mousetrap plan, any further steaming around would simply be hoping to get lucky by blundering into something juicy. And as we know, hope is not a battle plan. Hence the only reasonable strategy is to pull back and come up with another plan later.

Phenomenal research and great writing and analysis, Chief!

ReplyDeleteI'm not a Navy man but the hat's off to you...

Excellent as always Chief.

ReplyDeleteEnjoyed reading that one chief, excellent as ever.

ReplyDeleteThing is, Ael, I blame Ingenohl for the moral cowardice of approving the mission in the first place knowing that he couldn't justify risking the High Seas Fleet to the Kaiser if anything just like this happened.

ReplyDeleteHis decision that morning? No, given the constraints on his action, I think he made the right decision. But, frankly, the Scarborough Raid just highlights how faulty the strategic thinking of the Imperial Naval Cabinet and the KM staff was.

Like I said in the post; Germany had to WIN the war at sea to have a shot at winning the war as a whole (and even then I'd say their shot was 50-50 at best). Therefore the German Navy was worthless - or, worse, a huge drain on the German war effort - unless it was risked in an attempt to smash the RN distant blockade and open the sea lanes to German attacks on Britain's SLOC.

The German Navy - Ingenohl - should have gone to Wilhelm and laid it out in just those terms; you've built this terrific fleet, but unless you're willing to throw the iron dice and risk it all it's not going to do you any good and, in fact, will actively harm your country.

All the subsequent failures were, IMO, consequent to that. The RN didn't HAVE to be brilliant - they just had to continue to be there. The German Navy HAD to be brilliant, had to take the Big Risk, and the officers of Ingenohl's generation didn't have what it takes to do that...

Maybe I am a similar coward, but there are things that you can say to your boss and then there are things you just have to show him and let him make up his own mind.

ReplyDeleteThe German Admiralty had concluded that simply steaming out front of Scapa Flow and daring the Brits to come out would have gotten them all killed (and not improved the war situation). I.e. why roll the die if they are loaded against you.

Simply staying in port is less bad than losing the fleet. Every new ton of German battlewagon meant that the Brits had to build two. The Germans had a lot bigger

At least the raid idea was worth giving a shot. It seems clear that after the raid, the Germans did not think they could arrange a halfway fair shake of the die.

I have to say, I'm still not sure what the hell the KM was hoping to do with their surface fleet. They DID come out several times after Scarborough; Dogger Bank just a month later and then Jutland, of course.

ReplyDeleteI get that the Grand Fleet was just that much bigger; 25-28 battleships to the High Seas Fleet's 15-16, so a straight-up slugging match wasn't really in German interests. But the German plans to try and lure out a portion of the Grand Fleet and smash it were hopeless so long as the British were reading their mail, and they never seemed to figure that out. After Jutland the KM stopped even seriously trying that.

In a sense the British were in the same position that the U.S. is in southwest Asia; you're right that the German shipbuilding forced the British to devote more resources to her Navy than the Germans did...but the British had that much more Navy that they could afford to be lavish. And the RN was always going to be that big an investment in an island nation; the German activity didn't do much more than force British deployment to counter the threat to the North Sea.

But the German surface fleet was almost a complete waste of men and materiel.

Chief - - Good stuff! Glad to see you doing more naval battles. Are you going to post it on MilPub? Pretty slim pickings over there right now.

ReplyDeleteAmazing that even with the High Seas Fleet superiority in gunnery and ammo handling (and armor in the case of the battle cruisers) that they could never get momentum over the Brits. Just goes to show that the old saying ”…quantity has a quality of its own…” has a lot of truth. That and a good intel bureau like Room 40.

Massie's "Castles of Steel" that you mention does a great job – not only on Scarborough but on the naval war as a whole. I note that Massie's references include much from the German side that are not generally available at least here in Seattle. Massie attributes works from Admirals Scheer and Tirpitz, Waldeyer-Hartz’s bio of ”Admiral von Hipper”, and Korvettenkapitan Otto Groos’ ”War in the North Sea”.

A very complex story told well. Thanks, Chief.

ReplyDeleteNice work and well worth the wait. This story shows two major British weakness. They had a number of blockheads in key positions who cost them dearly. The ones who stand out are Milne, who let the Goeben and Breslau get away and was the subject of some memorable invective from Jacky Fisher even before that, and Beatty's flag lieutenant Seymour whose bungled signals also ruined British chances at Dogger Bank in 1915 and Jutland in 1916, because Beatty was too blind or stubborn to sack him for screwing up in 1914. Also there was a distinct lack of initiative in subordinates as shown by the destroyers slavishly following Lynx when she was hit and Arbuthnot refusing Orion permission to fire without orders from higher.

ReplyDeleteA further note on propellants is in addition to burning faster, British Cordite often had Vaseline added in the belief that it would stabilize the Cordite but in fact had the opposite effect, making it unstable and leading to spontaneous magazine explosions like the HMS Vanguard.

A final observation is that in both world wars the Kriegsmarine's surface fleet showed a distinct lack of willingness to engage the enemy and an astonishing willingness to scuttle their ships rather than go out fighting.

BD: All valid points, and go quite a ways at illustrating the differences between the institutional culture of the two navies.

ReplyDeleteThe RN had real issues with addressing technical and tactical problems. The vast inertia of the seniority system that had descended after Nelson's era meant that there were a LOT of people in positions of responsibility who got there just by "being there"; by not making waves and not backing losers. I love the young officer's comment on Warrender, how during peacetime his stolidity could pass for deep thinking but how wartime exposed the degree to which he wasn't really thinking much about his profession at all.

I think Massie lets Jellicoe off too easily; he had his own problems. For example, he recognized the shipbuilding and ammo handling issues before the war but wasn't willing to pursue them. British sailors died because Jellicoe was too much the Organization Man to rock the battlecruiser...

The Imperial Navy, on the other hand, never seemed to get over being intimidated by their British foes. You're right; their instinct always seemed to be to run away and sink themselves when push came to shove. Not that there weren't individual officers with the spark; but overall both the Imperial Navy and it's successor the Kriegsmarine suffered from the same basic lack of strategic vision and tactical confidence.

In the end Bismarck was right; Germany didn't need any sort of significant surface fleet, and anything more than a notional investment in capital ships was a waste of resources.

Good job!

ReplyDeleteI have a question regarding the maps, I dont see the armored cruisers depicted, I know they were very close to the 2ns BS and was wondering whether they were represented as the second column of three of the main body or simply not depicted and the 2nd BS was steaming on two columns.

The actual published tactical maps leave a bit of a gap with 3CS. In the first map they're shown sortieing from Rosyth in the Firth of Forth. The next time they're shown is on the final close-up map of the BCS and 2BS search patterns at the exit to the minefield gap; there the ACs are in line-abreast to the west of the 2BS.

ReplyDeleteSo on my 4am map I show the ACs as the line of smaller ships to the west of the 2BS on the run to the south; that was my guess as to where Warrender might have put them, given their axis of travel to the rendezvous point and their location on the final search map. I assumed that the 2BS would have been sailing in two columns of three ships - I don't really know if that was their formation, but it seemed like a reasonable guess, given the way the Grand Fleet seemed to like to sail in smaller divisions and only form long lines-ahead for combat.