Bay of Pigs (Bahia de Cochinos/Victoria de Girón), "Operation Zapata" and "Operation Pluto"

Dates: 15-19 APR 1961

Forces Engaged: Expeditionary Forces of the "Cuban Revolutionary Council" (Consejo Revolucionario Cubano) during Operation Zapata/Pluto -

Ground Forces: Brigade 2506

The organization that was formed for the purpose of, and succeeded in, landing on the island of Cuba in the spring of 1961 was centered around a "brigade" - that called itself a brigada asalto, "assault brigade" - that combined parachute infantry, regular "straight leg" infantry, a small armored contingent, as well as a "special forces" or commando element and administrative, support, and headquarters troops.

The unit was broken down into nominal "battalions" (most of which were roughly the size or barely larger than a U.S. Army infantry company) which the brigade website breaks down even further. These also differ significantly from the organization as reported in Hawkins (1961). The breakdowns to the order of battle in this post are taken from the brigade site.

Brigade Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 140 all ranks (including command and staff, engineers, medical, military police, commo, and assorted ash-and-trash)

1st Battalion (ABN) - Hawkins (1961) reports simply 177 all ranks. The website agrees, and breaks the unit down further into the following:

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC), 10 parachute infantrymen, 6 command and staff, 1 chaplain

Company A, 42 parachute infantrymen

Company B, 24 parachute infantrymen + 15 mortarmen with 3 x 81mm mortar systems

Company C, 44 parachute infantrymen

Company D, 10 parachute infantrymen, 3 x 57mm recoilless rifles with 7 crewmen, and 15 mortarmen with 3 x 81mm mortar systems

Hawkins (1961) reports that the five line "battalions" were all assigned 175 all ranks, but the brigade website reports different numbers for each unit:

2nd Battalion (INF) - 177 all ranks;

HHC, 15 infantrymen, 5 command and staff

Company E**, 43 infantrymen

Company F, 39 infantrymen

Company G, 42 infantrymen

Company H, 33 infantrymen

3rd Battalion (INF) - 151 all ranks

HHC, 7 infantrymen, 4 command and staff

Company K, 30 mortarmen with 6 x 81mm mortar systems

Company L, 28 infantrymen

Company M, 41 infantrymen

Company I, 41 infantrymen

4th Battalion (ARM) - 152 all ranks

#1 Company, 35 infantrymen

#2 Company, 42 infantrymen

#3 Company, 40 infantrymen

#4 Company, 28 infantrymen (reported to have included at least 1 x 57mm recoilless rifle and some unknown number (probably 4) 81mm mortar systems)

Tank Platoon, 20 armor crewmen with 5 x M41 light tanks, plus 2 commanders and a 5-man maintenance section

5th Battalion (INF) - 156 all ranks

HHC, 13 infantrymen, 4 command and staff

Company O, 38 infantrymen

Company P, 38 infantrymen

Company Q, 35 infantrymen

Company R, 28 infantrymen

6th Battalion (INF) - 138(?) all ranks

[at this point the order of battle begins to get sketchy. As noted above, the CIA internal report simply lumped the other infantry "battalions" as assigned 175 troopers. The brigade site, however, here gets truly weird. Here's how they break down 6th Battalion]:

Company U, 20 infantrymen

Company V, 6 infantrymen

Company X, 8 infantryman

Company Y, 8 infantrymen

Company Z, 16 infantrymen

Unassigned to a letter company, 68 infantrymen

7th Battalion (INF) is even worse. The brigade site simply lists 161 names without otherwise identifying their companies or positions. I don't have any way of resolving this, other than to assume that the recordkeeping within the brigade was either never well-kept or lost in the aftermath of the disaster. But I also don't think you can reconcile this with Hawkins (1961) and simply say, oh, well, the CIA knew the numbers so there just must have been another 14 guys there the brigadistas didn't know about..

I think Hawkins (1961) is just wrong; I think he is going off of the "authorized" strengths and didn't bother to chase down the actual bodies present on the beaches that April. But I think the brigadistas didn't keep great records, either - not exactly a shock, given the circumstances - so while I suspect their numbers are probably closer to the truth, I think there's some slop there, too. So far as I can tell there's no definitive answer to this discrepancy.

Weapons Battalion (INF) - 127 all ranks

HHC, 15 infantrymen

Machinegun Company, 22 infantrymen with an unknown number of M2 .50cal heavy machineguns

Recoilless Rifle Company, 22 infantrymen with 4 x 75mm M20 recoilless rifles

Heavy Mortar Company, 65 mortarmen with 7 x M2 4.2-inch mortar systems

Hawkins (1961) also lists the following:

Boat Operator Section - 36 personnel

Intelligence/Reconnaissance Company - 68 personnel

"Supernumeraries" - 43 personnel

Add all the Hawkins (1961) order of battle numbers up and you get the 1,511 number that everyone and their dog (including Wikipedia) uses for the number of brigadistas involved in "Operation Zapata"

The Hawkins (1961) report also provides a list of things like heavy weapons, including stuff not mentioned above, like 22 M2 60mm mortars and nine flamethrowers.

On the other hand...

The brigade website lists a huge slug of bodies in somethings called Batallon de Retaguardia Homestead which I translate as "rear detachment"; 102 names in the "Cruz de la Torre" unit and another 83 in the "Archa Sanchez" unit. I'm honestly not sure what to say about them. That's the equivalent of another full "battalion" sitting around the billets doing jack shit. Were they?

And, if not, what were they doing? I've got nothing.

Another piece of the operation that both sources mention is a group led by one Higinio "Nino" Diaz (described by Hawkins (1961) as "a Cuban exile leader in Miami...(and) a small force composed of his immediate followers"...) that the brigade site calls the "batallon especial" (Grupo de Nino Diaz) that was part of "Operacion Marte". Hawkins (1961) makes this group sound like they had no connection with the brigade, and the brigade site doesn't show them with brigade i.d. numbers, so I tend to agree; they were an independent group that was roped into the whole macguffin and, it should be noted, had just about the same sort of luck.

So how many brigadistas were on the ground (or near the ground, anyway) in Cuba in April 1961 depends on who you believe. The official CIA account claims 1,511. If you add up the brigade website you get something like 1,230 if you take just the maneuver units, and about 1,480 if you add in the weird "rear detachments" and the Diaz group.

We'll put a pin in that and move on to the...

Air Forces: Fuerza Aérea de Liberación (FAL)

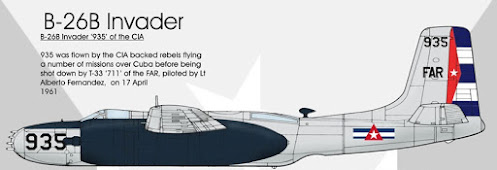

The primary offensive weapons the Brigade depended on to control the air over the invasion beaches were a total of fifteen Douglas B-26 "Invaders". The CIA had purchased the light bombers from USAF surplus stocks particularly because the Castro Cuban Fuerza Aerea Revolucionario had six of them. We'll get to that in a moment.

Despite the designation, this aircraft is not the same thing as the Martin B-26 medium bomber of similar vintage. The Douglas bomber was originally an A-26 (that is, an "attack" aircraft and wasn't given it's bomber "B-" designation until after WW2), had a crew of 3 compared to the Martin's 7, and was used for deep ground attack and secondary bombing missions - similar to the A-20 "Havoc" - rather than the way the Martin, or earlier B-25 "Mitchell" were used.

The A-26/B-26 was a good attack aircraft; fast and capable of carrying a relatively heavy payload for it's size (it's 6,000-pound iron bomb capacity was 50% greater than the larger Martin B-26). Testimonial to the value of the aircraft was that it served well into the late 1960s with the USAF and even longer with other nations.

Regardless of the qualities of the aircraft itself, the whole point of this exercise was to convince the world that a force of Cuban counter-revolutionaries was countering Castro's revolution. So the air support couldn't be a bunch of American warplanes buzzing around the Cuban skies - the air war had to at least look like Cuban vs Cuban.

Hence the FAL B-26's all painted up in FAR livery; to convince the People Sitting In Darkness that this wasn't just the usual heavy colonial hand of Uncle Sam but a true liberation force fighting the Evil Commies.

But.

In the sort of fuckup that we're going to see a...lot more of before we're through the CIA's purchasing officer didn't bother to check on what type of B-26 the defenders had.

So for weeks and months the trainers trained and the organizers organized and the FAL pilots flew and the planners planned and nobody bothered to think "gee, I wonder if we have the right kind of this bomber?"

They didn't.

The FAL's B-26B's were visibly different from the FAR's B-26C's, and the difference was absolutely critical to a vital maskirovka that was part of the CIA's plan, as we'll learn more about in a bit.

It's also worth noting - look hard at the silhouettes above - that one other problem with the B-26B's the FAL flew over Cuba was that to save weight both the ventral and dorsal turrets were removed. The FAL bombers were like a bull; dangerous to the front but just meat from behind.

The remainder of the FAL included two different types of transport aircraft; the twin-engine Curtis C-46 and the four-engine Douglas C-54. As detailed in Leeker (2015), although the FAL went through a number of both types during the training and run-up to D-Day only nine transport aircraft actually flew over Cuba in April; five C-46 aircraft that were used for a combination of paratroop drops and supply missions, and four C-54s used for resupply.

Sea Forces:It's hard to call these things a "naval force". True, they were in the water and, true, they were all the Brigade had, but a weirder congeries of boat-like things has seldom been assembled in the history of amphibious war since Xerxes' day.

The bulk of the little flotilla that arrived off Playa Giron on 17 APR 61 was composed of WW2 emergency program N3-type small freight carriers. About 250 feet long and powered by a steam-driven piston ("reciprocating") engine, these little ships were designed to be working-day vessels, puttering around delivering general cargoes. The five present at the Bay of Pigs included:

SS Atlantico

SS Caribe

SS Santa Ana

SS Lake Charles

SS Houston

We'll talk more about the actions of the little freighters when we get to the actual engagement, but suffice to say for now that while these vessels were perfectly adequate for moving things and people they were not designed to move them across an open beach, which was, again, all part of the whole "awshit" factors we're going to see again and again with this whole macguffin.

Two more "major" vessels were surplus LCIs - "Landing Craft, Infantry". These 158-foot long vessels were among the vast assemblage of over-the-shore delivery boats and ships developed for the Allied amphibious operations in WW2.The Wiki entry for these things reminds us that while they were the largest beachable landing craft of the Big War, "(t)he steepness and narrowness of either type of bow ramps made the LCI impractical for landing troops as part of an initial assault against a defended beach..."

That obviously wasn't a problem here, so the two included in the Zapata operation - the Blagar and Barbara J - were, unlike the N3 freighters, where they should have been on the morning of 14 APR.

The last "big" vessel included in this motley group was a former "Landing Craft, Tank" (LCT), the Rio Escondido.

Based on what I can dig up from various places on the 'Net it looks like the Rio Escondido was originally a "Mark 8" LCT but that it was more or less rebuilt completely in 1952, including a new powerplant as well as add-on sections fore and aft, which is why the 1961 Escondido looks nothing like the original Mark 8 hull did.

The critical piece of this rebuilding is that by April 1961 the Escondido could not do what it could have done in 1945; land troops and equipment over an open beach.

Rounding out the invasion "fleet" were seven actual landing craft, what you think of when you think "landing craft" - a small, steel- or wood-hulled boat with a ramp in the front. These consisted of three Landing Craft, Utility (LCU) types and four Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel (LCVP) types. All were too small to sail across the Gulf with the rest of the ships, and were delivered to the brigade by the US Navy when they arrived off the Cuban coast.

So.A roughly brigade-sized infantry unit (light tank platoon attached) with somewhere between 1,200 and 1,500 troops, about 30 mixed light attack and transport aircraft, and a small seaborne flotilla based around five coastal freighters and three old or converted landing vessels, so probably about 2,000 all arms. The ground force was under the nominal command of José Alfredo Pérez San Román, with the overall "civil" command belonging to Manuel Francisco Artime Buesa.

But all these people and aircraft and ships were just the activity going on in the foreground.

The Hand behind the Curtain: United States of America: DOP/WH/4

The open secret of the invasion was the guiding hand of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency.

We'll talk about this a lot more in the "Campaign" section, but the early Sixties were a Happy Time for the "operators" of the Clandestine Services, the covert ops guys, the inheritors of the old Wild Bill Donovan OSS tradition of swashbuckling adventures behind enemy lines.

The main reason for this was the Director, Allen Dulles, who luuuurved him some covert ops (and considered the actual "espionage" parts of intelligence as vaguely wimpy and un-American). In Dulles' Directorate of Plans the bad and the bold ran the show.

So you had the Greek intervention in '48, the Mossadeigh coup in Iran in '53, the Arbenez coup in Guatemala in '54, and the attempt to overthrow Sukarno in Indonesia in '57.

Beginning during the last year of the Eisenhower Administration the CIA's Western Hemisphere Division assembled a task force within Branch 4 (the section that handled Cuba).

This organization was set up to coordinate, train, deploy, and effectively command the operations of the Cuban exile forces during the run-up to the invasion as well as (assuming the plan had worked as intended) the ensuing counter-revolution that would take down the Castro government.

As detailed in Hawkins (1961), the U.S. through the CIA created the whole macguffin that ended up in the wilds of southern Cuba in April, from trooper's boots to an air force and navy. The process of doing all this included:

- "staff sections for planning and supervision of activities" including intel, propaganda, political, logistical, and tactical operations.

- air operations staff and direct support, including pilots from the U.S. Air National Guard

- training and operations facilities including a "forward operating base" in Miami, the former naval air station at Opa Locka in Florida (used for logistics and "black" transportation to the Central American sites)

Which included the main brigade training site at Retalhuleu in southwestern Guatemala, the staging facility at Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, as well as ancillary training and support bases at Eglin Air Force Base, Belle Chase Naval Depot, and on Vieques Island.

The total number of U.S. government and contractors involved may never be exactly counted up, but I've read estimates in the 500-600 range. This was a big operation, and for a "secret service" the CIA had a crap-ton of bodies swanking around, just another reminder that during this period a big part of the CIA didn't think if itself as a spy agency. Instead it was a sort of an undercover army, planning and executing military-like adventures the were too fraught politically to involve uniformed GIs.

This "we're an army but not like that army" way of thinking had some deep flaws in it that the events of April 1961 exposed.

República de Cuba, Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias (FAR) and Milicias Nacionales Revolucionarias (MNR)

I've had a hard time finding an order of battle for the Cuban defenders, largely because my rudimentary Spanish doesn't let me search effectively for Cuban government sources. Surely the FAR staff sections wrote after-action reports and, eventually, histories of the events of April 1961; the defeat of the Brigade was (and in some ways still is) the high water mark of the Revolution.

I just can't find them.

Here's what I do know.

The first (and most numerous) Cuban armed forces that met and fought the exile brigade were the "National Revolutionary Militia", the outfit that the government formed after the revolution against caudillo Fulgencio Batista in 1959.

The MNR in 1961 appears to have been a sort of local Home Guard, with a notional organization into battalions - that became more formalized when the original organization was reformed as the Milicias de Tropas Territoriales (MTT) - that was, at first, a handful of locals with whatever weapons they had stashed in the bohio when the brigadistas showed up around Playa Giron.

As it became clear that this was not just a tag-end of anti-revolutionary guerillas, though, the FAR higher did form up the MNR into their battalions. What I'm having a hard time finding, though, are things like the composition of those battalions, where they went and what they did.

In this I don't feel too badly, though. People getting paid to write about this fight, such as the author of the Osprey book (Quesada, 2009) that covers the invasion, are also reduced to guessing; his "order of battle" is prefaced by the caveat that "Elements of the following (units) are believed to have taken part..."

So, for a geologist in Portland to have to guess at units and strengths?

Yeah, okay.

In the "chronology" of the invasion posted at the U.S. National Security archive several units are mentioned by name, so there's at least agreement among U.S. analysts of their involvement. These include both Revolutionary Army - "regulars" and militia.

Any heavy weapons units involved in the fighting at the Bay belonged to the FAR. Infantry could come from either the regulars or the militia, but only the Revolutionary Army had armor and artillery.

Armor

In 1961 the FAR had a single armored division, listed as based at Managua, which is a district of the capital of Havana. By early 1961 the Soviet arms dealers had shipped a bunch of WW2-era T-34/85 tanks to the FAR, and from all the photo evidence it was this type that was sent to Matanzas province.

Based on the chronology, here's where we know the tanks went:

Four T-34s are listed as supporting the Cadet Battalion moving south from Central Australia to Playa Larga at 1100hrs, 17 APR.

"A tank company" arrived to reinforce the same element around midnight, 17/18 APR.

"15 T-34s" are said to have been sent to Yaguaramas on 18 APR (at 0900 on 4/19 two companies of infantry are reported to have "moved out" from Yaguaramas with 10 tanks - presumably from this same unit)

At 1000hrs 4/19 at least three T-34s support the Police Battalion attacking the west side of the final Brigade position at Playa Giron. How many more than three is hard to tell; we're only told that three are destroyed.

That's it.

A WW2 Soviet tank company fielded 10 tanks; by the middle of the Cold War this had been increased to about 13 to include company command vehicles. So it's not unreasonable to assume that Cuban tankers 1) would have largely copied Soviet organization, meaning 2) would have arrived at the battle as 10-tank companies, so any group of tanks smaller than that was a subunit; a platoon, or just a piece of a company that was all that could be shoved on the flatbed and driven like hell to fight the imperialists.

Presumably at least one company, and probably at least part of another, went to the west side of the Brigade AO between 17 and 18 APR. This unit or units also supplied the tanks that supported the Police Battalion attack on 19 APR.

Another one-and-a-half companies were sent to the northeast sector and were involved in the fighting there on 19 APR.

So let's say about three companies (the better part of a tank battalion, although which one we don't know) of T-34/85 tanks. Given that troop strength of a Soviet armor company was about 90 tankers, figure something like 270-300 treadheads.

Interestingly, the museum in Playa Giron has an SU-100 assault gun on display, implying that at least one vehicle of this type was involved. All the photos from 1961 show T-34s, though, so hard to say where (or even if) any other armor units or individual vehicles were engaged.

Artillery

The artillery doesn't show up nearly as well as the tanks; unsurprising, given the supporting nature of the arm. Cannons are mentioned only twice in the chronology:

"Four howitzer batteries" are said to have arrived with the reinforcing column (the one with the tank company) that arrived in the Central Australia/Playa Larga western sector around midnight 17/18 APR.

"Two batteries of 122mm guns" are said to have been sent to Covadonga 18 APR.

Interestingly, Quesada (2009) has actual unit designations for some of these Cuban redlegs; they are listed as Battery 3 and 11, Camagüey Battalion, and the "Baracoa base battalion". To square this with the chronology you'd think that the two numbered batteries are the 122mm guns and the other four batteries are from Baracoa, but there's no way to be sure.

Quesada (2009) also includes a militia battery ("Battery 3"), but given the state of the MNR in 1961 this seems a bit of a stretch.

The photograph from the fight above - the only one I could find - show FAR gunners serving what appear to be Soviet 122-мм корпусная пушка обр. 1931/1937 гг also known as an "A-19". But the batistianos had left behind a quantity of U.S.-made cannons, presumably largely M101 105mm guns, so the Baracoa unit might have brought these to the engagement.

Either way, at least six batteries, presumably between 36 and 48 towed 105mm to 122mm cannon and probably about 500-600 redlegs.

In the chronology a "Battalion 1" of the FAR Special Forces is alerted by Castro as 0345 17 APR; the text states that Castro calls this unit, "...located in Cojimar, east of Havana, and orders Captain Aroldo Ferrer to send troops to the Marsh and await orders." The unit is not further mentioned, so it may have remained in position and not engaged; other than this unit I can't find any evidence of the participation of regular army infantry.

InfantryThe Cuban defenders had something like 25,000 "regular" infantry of the FAR and 200,000 MNR reservists available nationwide in April 1961, along with perhaps 9,000 to 10,000 policemen who could be used as soldiers in a pinch.

As noted above, the regular infantry doesn't appear to have turned up in force to fight the invaders, but the militia certainly did; at least ten battalions are mentioned by name in the chronology, along with a "Police Battalion" and the ad hoc battalion from the Leadership School.

And Cuban battalions were big; the numbers we have suggest something around 900 all ranks; the leadership school turned out 875 troops, and a battalion of militia posted near the Central Australia sugar mill is listed as 900 strong.

So, based on the presence of Militia Battalions 111, 113, 117, 123, 144, 180, 225, 326, and 339, the Police and Cadet Battalions, as well as the elusive Special Forces unit the chronology suggests that the Cuban defenders had something like 8,000 to 9,000 infantry mobilized to the coast of Matanzas province by 19 APR 1961.

Quesada (2009) provides a slightly different list. Along with the Police and Cadet units, his fifteen MNR battalions engaged include several not mentioned in the chronology (23, 114, 116, 120, 148, 211, 219, 227, and 303) but he omits Battalions 111, 123, 144, and 326. Even so, his total would come to something like 15,000 infantry.

I'm going to guess that the Quesada (2009) numbers are closer to the truth, although which militia units were present may be difficult to determine without a better understanding of Cuban sources.

Ground Forces, Republic of Cuba - so based on our sources and best guesses, we're looking at roughly 15,000 infantry (ranging from true irregular militia to semi-professional/trained reservists), 600 artillerymen with something on the order of 40 towed 122mm or 105mm gun systems, and 300 armored crewmen with 30-40 T-34 (and possibly a SU-100 or two...) tanks.

Air Forces (Fuerza Aérea Revolucionaria)

The air arm of the "Revolutionary Force" was at a low point in its history in 1961. The batistiano leftovers, which included all sorts of WW2 airframes like P-47s and P-51s, had fallen apart after the revolution.

I've read that of the maybe about 36 flyable - that is, still with startable engines and working controls - aircraft littered the airfields around Cuba only 18 were operational, and the best Cuban pilots were in eastern Europe training on Soviet aircraft.

What the aerial version of the FAR had, though, which the exile's FAL did not, were actual air-to-air combat aircraft.

Along with six B-26C bombers the FAR pilots of the Escuadrón Persecución y Combate had a dozen fighters; six Hawker Sea Fury propeller-driven fighters and six more Lockheed T-33A jet aircraft.

We've talked about the B-26 already, so let's talk a moment about the fighters.

The Sea Fury was a midwar development the RAF intended to use to replace the Tempest and Typhoon fighter/fighter-bombers. When the end of the war came into view the RAF cancelled their version of the program but the Royal Navy's air arm didn't; they had been putzing along barely satisfied with versions of land-designed fighters like the Seafire and Sea Hurricane. The opportunity to develop a better aircraft was too good to miss, and so the Sea Fury operated off RN carrier decks well into the 1950s.It was a good bird; faster than nearly all of the WW2 piston-engine fighter/interceptors and reportedly capable of at least holding it's own against the early jets like the MIG-15. It was also, like the Tempest it followed, a very effective ground attack platform.

Hawker sold Sea Furies to places as far apart as Burma and Egypt in the Fifties. The Cuban aircraft had been purchased by the Batista government in 1958 and inherited by the FAR after the dictator grabbed a hat.

The T-33s were also Batista remainders, shipped to the island in the mid-Fifties under the Major Defense Acquisition Program that has supplied so much of the world with U.S. weaponry.

What I find interesting is that the T-33 is usually described as a "training" aircraft and, yes, by 1961 it was not a frontline fighter. But the basis for the airframe was the first U.S. jet fighter, the P-80/F-80 that soldiered on into the early 1950s where the straight-wing design was shown to be deadly inferior to the early swept-wing jets like the MIG-15 and the F-86 Sabre. This wasn't some sort of weird experiment, like hanging rockets off the wing of a Curtis Jenny. The T-33 was constructed as a jet trainer but it had a fighter pedigree.

So while the Cuban aircraft were indeed built and sold as "trainers", they were "trainers" in the same relation to the F-80 that the Camaro on your street is to a NASCAR Camaro; based on the same chassis and capable of some similar operations if armed and flown as such.

As far as the actual numbers engaged, all eighteen FAR aircraft got into the show, and made a crucial difference, as we'll talk about to excess.

Marina de Guerra Revolucionaria (MGR)

In 1961 the "Revolutionary Navy" was, like the air force, living off the remnant hulls of the batistiano force. Worse, after initially transferring the pre-revolutionary sailors into the Rebel Navy, Castro's people had discovered that being against Batista didn't mean being for Castro, so by the end of 1960 the old navy had been largely dispersed and a new cadre of future naval officers and chiefs were training in the eastern Bloc.

Like the sailors, the ships of the as-yet-not-named-MGR were not ready to fight. The batistiano Navy had no capital ships and was composed largely of WW2-era wooden subchasers and patrol boats.

One of these, the El Baire, was sunk by FAL aircraft 17 APR near the Isle of Pines well to the southwest of the invasion beaches. No other Cuban warships were involved in the engagement at all.

So probably something like roughly a division's worth of assorted militia infantry supported by regular army tanks and artillery and eighteen assorted aircraft, perhaps 15,000 to 16,00 troops all arms. The ground troops appear to have been largely under the command of Commandant José Ramón Fernández Álvarez, while the entire Cuban defending force was under the overall direction of Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz, then Prime Minister of the Republic of Cuba.

The Sources:

Given it's setting in the middle of the 20th Century you'd think that there would be little difficulty in getting information about the events that led up to and occurred on the south coast of Cuba in April of 1961.

And you'd be right; in that a lot of the basics of what we call "The Bay of Pigs Invasion" are well documented in newspaper accounts, magazine articles, television news and, later, documentary films about the events.

However, it's well to consider several potential issues.

First, the Bay of Pigs was part of a now more than sixty-year long propaganda war between the United States and it's affiliates and Cuba and it's partisans. The Soviet Union has gone, but the legacy state of Russia remains and the questions raised about American subterfuge by the actions taken by the U.S. in and toward Cuba during the early Sixties have been, if anything, intensified rather than dispelled by American adventures overseas since then.

Second, remember that for all the lack of actual secrecy that turned out to be typical of Operations Zapata and Pluto the CIA was still a "secret service", and some of its secrets are still secret. And the Cuban government was a dictatorship then - or well on it's way to becoming one - and still is today, and dictatorships are also kind of notorious for keeping some unflattering things secret.

Fortunately for us, the passage of time has taken the edge of the Agency's need for secrecy, and we can access many of the primary source accounts.

As always with this series, I'm going to concentrate on the information you can find online. The subject of the Bay of Pigs has generated an immense volume of print, as well, so I can't really avoid mention of these sources, as well.

General Sources

Perhaps the Q for the CIA account of the operation is the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) site. It contains a compendium of the accounts assembled in the late Seventies and early Eighties by the official historian Jack Pfeiffer, including links to his review of the October 1961 CIA Inspector General's survey of the "Cuban Operation". The IG document was highly and unsparingly critical of the operation. Pfeiffer's rebuttal is likewise unsparing.

Mind you, Pfeiffer himself wasn't an untainted body. In his article about the internal dogfight within the CIA that these paper battles record, Lockhart (2016) described Pfeiffer's work as:

"...of unprofessional quality and it fails to advance the discussion much. On the other hand, it does offer some details on Kirkpatrick’s staff and their methods unavailable elsewhere, and it summarizes some of the discussions that occurred at the CIA’s highest levels just after the inspector general distributed his report. We should also understand that all of this was about much more than the Bay of Pigs. It was part of a larger power struggle over what kind of intelligence service the CIA should be."

Included in the FOIA dump is Pfeiffer's summary and review of the so-called "Taylor Report", the product of a commission formed by then-President Kennedy to investigate the events that led to the disaster. This commission was headed by former Army Chief of Staff GEN Maxwell Taylor but, curiously, included several of the major players in the operation, including CIA boss Dulles, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, and Chief of Naval Operations ADM Arleigh Burke.

That report has been declassified, as well. It's huge, and difficult to find online. Some pieces are found at the George Washington University National Security Archive here. The cover letter and four summary memos prepared by the Commission for Kennedy are contained on this page of the State Department archives; you're looking for documents 230 through 234 dated June 13, 1961.

COL Jack Hawkins, chief of staff of the "paramilitary" section of WH/4, wrote a memo to file in May, 1961. This "Record of Paramilitary Action Against The Castro Government of Cuba", dated 5 MAY 1961, is accessible in pdf form here. Obviously Hawkins has an axe to grind against the Kennedy administration, but within those limits his information is useful. I've cited him as Hawkins (1961).

The GWU National Security Archive has a bunch of other good information, including the proceedings of the 40th anniversary meeting in 2001 here, as well as the "chronology" timeline of events assembled from numerous sources here.

Sources - Air Assets and Air Operations

Volume 1 of the Pfeiffer summary at the FOIA site contains good information on the FAL and Brigade air operations in general. Another interesting secondary source is the work I've cited as Leeker (2008) that puts Operation Pluto in the context of the CIA's "Air America" adventures of the Sixties. A bit of a more popular-press article about the air war over the invasion beaches, Correll (2017), is in the May issue of Air Force Magazine, and a third (MacPhail, 2019) covering the FAR pilots and their aircraft is found in the Latin American Aviation Historical Society (LAAHS) website.

Sources - Naval Assets and Offshore Operations

The original sources for the offshore portions of the engagement are less numerous and less complete. Hawkins (1961) provides an overview of the planning and the operations, but assumes the reader understands what an LSI or LCU looks and acts like. There's a fun little article (McNamara, 2020) in an online journal called American Shipper that provides more detail on the exile fleet. Information on Castro's sailors is nearly impossible.

Secondary Sources

As I mentioned, the mess that blew up in the Kennedy administration's face in April was a huge and public mess and, like that sort of mess tends to do, drew journalists and analysts like flies. The resulting printed works are almost too numerous to list, but one place to begin might be here, Playa Girón/Bay of Pigs: Washington's First Military Defeat in the Americas by the old caudillo himself, Fidel Castro.

Surely El Jefe provides a purely objective historical account. Can't imagine any issues here.

If you're interested in a similarly slanted view from the other side of the beach you might try Haynes Johnson's 1964 The Bay of Pigs: The Leader's Story of Brigade 2506.

I used Jim Rasenberger's 2011 The Brilliant Disaster: JFK, Castro, and America's Doomed Invasion of Cuba's Bay of Pigs heavily while researching this post. It seems relatively balanced, well researched, and especially benefits from the recent declassification of many of the original source documents.

It also reads easily, especially for a history, and makes clearly follow-able what was often a chaotic and bloody mess.

One of the very early and very popular accounts of the invasion is also one I consider should be treated with care; Arthur Schlesinger's 1965 A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House. We'll talk about this more in the "Campaign" section, but the things to keep in the front of your mind when reading Schlesinger is that 1) he was a very loyal Kennedy partisan, and 2) he was a strongly vocal opponent of the CIA's invasion plan. Rasenberger (2011) details the extent to which Schlesinger tried to derail the CIA train, the effect his and other opponents within the adminstration's efforts had on the operation, and the resulting conflict over responsibility for the debacle.

Useful primary source, but biased, so use with care.

The Osprey people have produced a useful little entry (Quesada, 2009) that I also found helpful.

The Wikipedia entry is among the best of the type; generally well written, thoroughly researched and footnoted, and comprehensive.

And if the combination of dark and bloody history with interracial romance is more to your taste, you might sample Bay of Pigs Girl by someone named Dick Thomas (seriously..?) which is described as:

"In a town beside the Bay of Pigs, Jack meets Helena – a quiet and gentle mulatta.

After settling in together, Jack leads a quiet life of morning swims and domesticity, with time to reflect on a failed marriage and the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion.

A celebration of Fidel Castro’s rout of CIA-backed mercenaries leads him to a startling conclusion about the Cuban Revolution. It’s not socialism that holds the country together.

It’s something else."

Yes, Jack, it's something else, indeed!

The Campaign:

The last time we ran across the Cuban Revolution here at the Fire Direction Center we saw the Rebel Army put the batistiano soldiers at Santa Clara and Yaguajay - and by doing that put the Batista regime - to the sword in December 1958.

Batista caught the Air Caudillo flight out of Havana 1 JAN 1959, and the new government (under the nominal presidency of a man named Urrutia Lleo, an old-school anti-batistiano leader) took office the following week.

But the real drive behind the Revolution came from the leader of the 26th of July Movement, Fidel Castro, and the road that led to the Bay of Pigs was largely built because of Castro and his personal and political convictions.

Castro himself denied being either a dictator or a communist of the original Marxist flavor when he set up his crib in the penthouse of the Havana Hilton. I'm honestly not sure if he was kidding himself, or everyone else.

But his actions made it clear that regardless of what he said, Castro certainly acted like he saw Cuba as a dictatorship of the proletariat.

Batistianos were defenestrated. Many were tried, more than a few were executed in the name of "revolutionary justice". The underworld-run-in-broad-daylight by the North American mob was shut down; you'd think a civic virtue, but the mob stuff, the dope and hookers and gambling, was sunk deep in Cuban politics and Havana "society".

Worse, at least in many of the eyes watching from The North, Castro and his people weren't content to just cut off American gangsters at the knees.

The revolutionaries saw the foreign corporations and wealthy capitalists that controlled so much of the Cuban economy - in particular sugar, which was, as we discussed in the lead-up to Yaguajay and Santa Clara, the single biggest agribusiness in that economy - as just a different sort of gangster.

Through the spring and summer of 1959 the new government continued to turn the Cuban world upside down.

In May then-Prime Minister Castro broke up the big estancias and plantaciones - the ranches and sugar plantations could not be larger than 1,000 acres - and forbid foreigners to own them. In the summer the Castro government nationalized the American sugar company plantations outright, as well as sugar and oil processing. Hershey and U.S .Sugar and Kellogg and all the other extranjeros screamed like wounded eagles.

Castro told them to pound sand.

At the same time, mind you, Castro tried to romance the former sugar daddy of his old enemy Batista, touring the U.S. like a rock star, wowing the crowds in Washington and New York City in April 1959.

Eisenhower wouldn't meet him, but he met up with Vice-President Nixon and had the good taste to loathe the man.

The romance was fated never to be. By September Castro returned to New York and delivered a four-hour tirade all about the perfidious Yankees and their evil doin's in Latin America to what must have been an utterly poleaxed audience at the United Nations.

By October tensions between the two sides were rising. A bizarre stunt involving a WW2-surplus B-25 appearing over Havana and bombing the streets with leaflets condemning Castro drove El Jefe into a snit and showed the first signs of the Miami Cuban opposition to the revolution. Castro responded with a fire-eating performance in front of a big rally in front of the Presidential Palace where he compared the leaflet-bomber with Pearl Harbor and accused the perfidious Yanquis of plotting to overthrown the revolution and return Batista to power.

And, as it happened, the Yanquis were, indeed, planning something very like that.

December 1959-April 1960: Wars and Rumors of Wars

On 11 DEC 1959 the head of the Western Hemisphere Division of the CIA, a man named King, submitted a memo to Dulles recommending the overthrown of Castro and his revolution within the coming year.

The importance of this memo to our topic is that it included the kernel of what became Operation Zapata; that an anti-Castro Cuban force invade the island, secure a lodgement, and invite in (or foment from internal resistance) a junta to replace the rebel leadership.

It also, either as a means of ensuring the success of the invasion or as an alternative to invasion, suggested assassinating Castro himself.

In January 1960 Dulles directed his deputy director for plans, a man named Richard Bissell - he's the guy in the photo above - to set up a working group that would craft an operation to remove Castro. On 13 JAN Dulles requested that the "Special Group" of the National Security Council approve covert action against Cuba. This approval was granted.

This "Special Group" is an interesting critter, and important to understanding the progress of paramilitary action in the Caribbean during the last Eisenhower year.

It was dead solid top secret, created in 1955 by executive order. The members included the National Security Adviser, The Director of Central Intelligence, as well as assistant secretaries of State and Defense. It was designed to set up and keep track of "covert operations" - that is, coups, assassinations, sabotage, armed actions all the way up to guerrilla wars, and other "dirty war" kinds of shenanigans. These were all considered by Eisenhower's Special Group in the first months of 1960.

Rasenberger (2011) does a nice job of summing up how ridiculous this all was:

"How strangely the future came to pass. For months, Castro had been predicting that the United States intended to invade his country. For months, American officials had been predicting that Castro was falling into the Communist embrace of the Soviet Union. At the moment each side began to suspect the worst of the other, its suspicions were ill-founded, even paranoid.

That was no longer the case by the start of 1960."

In early March the French freighter La Coubre, loaded with Belgian munitions, exploded in Havana harbor.

Nobody admitted knowing anything and, indeed, munitions carriers had exploded before without any human intervention other than carelessness or stupidity. But the Cubans had suspicions, and Castro himself had no doubt; this was an American act of war.

And the Americans were, indeed, starting to think that way. On 17 MAR Bissell presented the CIA's official plan; "A Program of Covert Action Against the Castro Regime", to President Eisenhower (along with his vice-president, Nixon, Ike's secretary of state, and ADM Burke representing the Joint Chiefs).

This wasn't the actual invasion plan. It recommended overthrowing Castro by:

- ginning up a political opposition group among Cuban exiles,

- setting up a "Radio Free Cuba" in the Caribbean,

- forming an exile undercover organization to carry out intel and sabotage operations within Cuba, and,

- begin training an "adequate paramilitary force" of exiles that was seen as potential guerrillas and insurgent-trainers in the style of the Castro rebel army for a domestic uprising in Cuba - basically a version of the organized guerrilla bands that operated in some parts of France and Italy, or the Soviet partisan groups, during WW2.

The most critical part of this plan was it's creator, Richard Bissell, and it's worth taking about him for a moment.

A Man, A Plan, A Can...no, wait, wrong spics.

Bissell was an American noble in the East Coast aristo, Groton-and-Yale, yacht-and-summer-home tradition. He was a pedant with the sort of truly peculiar affectations of his class - one of his hobbies was collecting and poring over railroad timetables - but he was also physically daring and, on his own terms, ruthless.

He'd been an organizer and planner during and after WW2; first organizing transport for the War Shipping Administration and then as inside the Marshall Plan. He seems to have be an exceptionally gifted bureaucrat.

Allen Dulles recruited Bissell in the early 1950s, and that decade saw two of his greatest successes.

In 1954 Bissell orchestrated what may have been the world's weirdest coup, against President Jacobo Arbenez in Guatemala.

Arbenez had been elected - democratically, or at least democratically enough - in 1951, but had begun to talk about things like social justice and political equality that to a Fifties American politician sounded ominously Commie-like.

So Bissell and a guy named Barnes went to work. Barnes ran the propaganda mills, while Bissell contracted a flea market air force to fly over Guatemala City and drop "bombs" including - I'm not kidding - empty Coke bottles that made a loud pop! when they landed.

The combination of hate radio, phantom rebel army, and exploding pop bottles spooked Arbenez, who ran for it, and Bissell got the personal thanks to Bissell and the CIA.

(The long-term shakeout of the Arbenez coup was decades of corruption, rebellion, dictatorship, and civil war that, generally speaking, created more troubles for El Norte than Arbenez ever could; many of the "caravans" of Guatemelan refugees haunting the nightmare of FOX viewers are the end-product of Bissell and Barnes, Inc. But that wasn't obvious in 1954.)

The other big success was Project AQUATONE which was, believe it or not, the Lockheed U-2.

Bissell was the CIA officer in charge of ramrodding the spy plane development, and he brought the project in twenty months and 3 million under budget.

By the spring of 1960 Richard Bissell was a guy with "a lot of topspin". It would be his job to set up and run "Branch 4" of the Western Hemisphere Division - WH/4 - and figure out how to rid the United States of this meddlesome Castro.

One of Bissell's most salient characteristics is supposed to have been his self-confidence. The guy was a supreme persuader, and was known for having unshakeable faith in his own judgement and his mission. These seem to have served him well in Guatemala and in the skies above the Soviet Union.

Whether they would do as well in Cuba would be seen.

Bissell's crew included his old pal Barnes and another Guatemala hand, a guy named Jake Esterline. A third character from Guatemala, named Phillips, was the psyops guy who was tasked with the counterrevolutionary radio.

Among the other almost-600-odd denizens of WH/4 were some familiar names from my youth; Richard Helms, who became Dick Nixon's victim after he refused to help cover up Watergate and, on the other hand, E. Howard Hunt, who organized - if that's the right word - the burglary.

The political affairs officer was a guy named Droller who didn't speak a word of Spanish.

Whatever their background, whatever their skills, this crew was supposed to be the point of the spear that would kill Castro's revolution.

The Plot ThickensSo this was pretty much the story between the spring of 1960 and the election in November:

- the CIA trainers and organizers worked with their Cuban proxies and assembled the wherewithal to defenstrate Castro and Che and their buddies, while

- Castro, Che, and the gang received a constant stream of whispered warnings that the Yanquis were coming for them.

Because, let's not kid ourselves; like love and a cough, a thousand-man paramilitary outfit, complete with aircraft and ships, can't be hid.

Meanwhile the gang at the CIA was also brainstorming nifty ideas like hiring the Mafia to assassinate Castro. Yes, really. Unsurprisingly the hoods took the cash but failed to come through, but it was the thought that counted.

The really critical juncture in this macguffin, though, is when the CIA's plan changed from some vague sort of super-guerrilla/partisan/Maquis-type operation to an actual D-Day invasion.

And a lot of that had to do with domestic American politics.

Specifically, with presidential politics.

Because, much as we kind of love to think of John F. Kennedy as King Arthur of Camelot, the people's hero, the actual JFK was a hardcore Cold Warrior. He ran hard in the summer and fall of 1960 on the Eisenhower people's being soft on Communism in Cuba. His opponent who, remember, was Ike's Veep, fought back, but was confronted with the undeniable reality that there the bearded bastard Castro was, puffing his stogie in Havana.

Kicking Around Dick Nixon - a political interlude

There's a great story about how the Nixon-Kennedy debates got wrapped around this whole Cuban adventure.

The fourth debate, aired in the third week of October 1960, was supposed to be mostly about foreign policy.

Kennedy had gotten his first confidential briefings, which covered some of the covert activities going on under Ike, when he was nominated back in July, and Nixon had been insistent that Dulles not give the Democratic candidate the details of the Cuban expedition, and Dulles claimed he hadn't.

So that was where things stood on 20 OCT 1960, when Nixon opened the afternoon paper and read that Kennedy had slapped at Ike's failure to eliminate the Cuban Menace and said that a Kennedy Administration would "strengthen the...democratic anti-Castro forces in exile...(that) have had virtually no support from our government."

Nixon was furiously angry (Nixon was good at being angry at his political enemies, if you recall...). He was sure that Dulles had blown the gaff, either in July or at another briefing in September, so Kennedy was ratfucking him - accusing Nixon's side of doing nothing while knowing they were doing just what Kennedy claimed he'd be doing...and knowing that Nixon couldn't say anything because the whole thing was a secret...

Instead, Nixon went on the attack in the debate the following evening.

Because he believed that Kennedy's announcement compromised the security of the plot (which, let's remember, Castro's intel people were getting whispers about the exiles now training in Guatemala all the time...) Nixon was placed in the bizarre position of having to call out Kennedy as a dangerously mad hawk for arguing for the very policies that Nixon was secretly taking part in.

He did, he lied for his country, as he saw it, and Nixon believed that his "patriotic lie" helped Kennedy beat him in November. This had a profound effect on Nixon.

He had allowed himself to be sandbagged. It was a mistake he'd never make again. "I vowed I would never again enter an election at a disadvantage by being vulnerable to them (the Kennedys) - or anyone - on the level of political tactics." (Rasenberger, p. 94)

Twelve years later he would make sure he wasn't.

The Plans Are Changed

In August 1960 Eisenhower had bumped up the budget for the Cuban operation by over 400% to 13 million, showing his continued interest. At the same time Bissell's CIA team was getting increasingly unhappy with the original guerrilla/infiltration plan. The people and groups inside Cuba were hopeless, the Cuban security forces were efficient, infiltrators were routinely captured, and airdrop of military supplies were usually off-target.

On 4 NOV, WH/4 sent a new set of mission orders to the training base in Guatemala.

These shifted training from infiltration and guerrilla action to training up "One or more infantry battalions each having about 600 men...to seize and defend lodgement in target by amphibious and airborne assault."

Here we should probably stop and talk about one of the most common tropes associated with this event; did the CIA gin up the entire Cuban exile part of the operation to force the U.S. government to back their play with hard power? Was the entire idea to put proxies on a Cuban beach and make them hostages to an American president's willingness to send Marines and sailors to save them?

Aside from pure QANut-grade conspiracy-theory goodness, the main driver for this is a memo prepared by CIA officer Richard Drain in November 1960.

Drain was feeling pessimistic about the whole op, and his memo reflects that. He wrote:

"Our second concept (1,500-3,000 man force to secure a beach with airstrip) is also now seen as unachievable, except as a joint Agency/DOD action."

This memo has been interpreted as giving away the CIA's internal knowledge that their Cuban exile plan was a no-go from the get-go, and that the thing was always intended to pull in the "DOD" - that is, American forces.

It's a compelling argument if you assume that the CIA was some sort of Illuminati pulling strings to make the U.S. government puppet dance...and you can keep making that case when you look at the sort of other skulduggery Kennedy's New Frontiersmen got up to in other places like Vietnam.

(And not just Kennedy's people; Rasenberger says that in a NSC Special Group meeting in November 1960 Eisenhower's national security adviser Gordon Gray suggested that the U.S. should somehow fake a Cuban attack on the navy base at Guantanamo Bay and use it as a casus belli. Why had didn't have the brass balls to call his scheme "Operation Gleiwitz" I have no idea; some people just have no respect for tradition.)

But given the priors?

I don't buy it.

For one thing, if the entire plan depended on U.S. military cooperation you'd think that the CIA team would have - at least on the downlow - gotten some help from the service chiefs. Sounded them out on possible ways that a U.S. backup could happen or be made to happen. While the Joint Chiefs were in the loop (ADM Burke, the CNO, was supposedly the most hawkish on the plan) nothing specific was ever arranged. It was all informal and talk-centric.

For another, the panic and furor that broke out when the airstrike plan was changed (we'll get to that, trust me - it's that important) suggest that the Agency planners had no hope then to get USAF or USN aircraft over the beach.

Yet another is that the Davis memo is really the only significant suggestion that the planners seriously thought that the exiles were doomed before they started. Every other document we have from the planning phase reads like the Hawkins 4 JAN memo to the project manager Jake Esterline. It's worth discussing for what it reveals about the CIA team's thinking for the Cuban Project at the time.

In it, COL Hawkins says that:

1) The landings will be preceded by airstrikes that will "destroy or neutralize" all Cuban government tac air and naval force that might be a threat.

2) The landing force mission is to "survive and maintain integrity" in Cuba. It's not to actually invade; it's there to spark a counter-revolution.

3) Which is absolutely gonna happen; the thousands of Cubans who are lurking will see the heroes on the beach and rise up.

What's also worth noting is that three-and-a-half months before the first boot stepped ashore Hawkins is utterly insistent that the invasion has GOT to have complete air superiority even before the boots get wet; "It is axiomatic in amphibious operations that control of the air and sea in the objective area is absolutely required."

Which is, yeah, well, no kidding; these guys, many of them, had learned their over-the-shore trade the hard way twenty years earlier, against the Japanese in the Pacific and the Germans in Europe. Nobody on the planning team expected their Cubans to go in without the sort of air cover the U.S. had put up over Normandy or Saipan. That's just how beach landings worked.

The problem was that nobody seems to have managed to square that with the political imperative that ran through both Eisenhower's and Kennedy's administrations. It was best expressed by Ike in one of the project meetings in late November;

"Are we being sufficiently imaginative and bold, subject to not letting our hand appear?"

That was the bright line for the American political leadership; get Castro...but don't let the rubes see the hand holding the knife. Remember the press releases; this is the Arsenal of Democracy. There could be no going back to the Bad Old Days of gunboat diplomacy.

If Castro slipped in the shower, or his cigar exploded? So long as there wasn't a "Made in the U.S.A." on the cigar band...fine.

But nothing obvious, and that would become the problem.

Getting There IS Half The Fun

So the winter and early spring of 1961 were a continuation of the autumn of 1960; the Cuban exiles trained, in Guatemala and elsewhere. The CIA planners planned and organized; ships had to be hired, the pilot training program advanced (Air National Guard pilots were eventually brought in to fill out the B-26 seats as the Cuban exile numbers couldn't be found).

In January the CIA brought Defense staffs below the Joint Chiefs level into the planning process. The response from the uniforms wasn't exactly thrilling; MG Gray, the liaison between the Agency and Defense, considered anything that landed a force less than 5,000 effectives would be disastrous.

But the timeline was tightening.

The Castro government had abandoned any pretense of courting the U.S. and was taking shipments of Soviet and other Warsaw Pact arms and supplies. Cuban FAR pilots were training in Eastern Europe on Soviet-made jet aircraft, so presumably as soon as they were qualified the Cuban government would have frontline MiG fighters and fighter-bombers. And the Cuban rainy season began in April, which would make everything, especially air cover, more difficult.

This was all presented to the new President Kennedy in a meeting on 28 JAN. Dulles made the case for the CIA invasion plan creating a "free Cuba" that the U.S. - with any luck including US-friendly Latin and South American countries from the Organization of American States - could then officially recognize and "support", presumably by force.

Kennedy asked for a Department of Defense evaluation of the plan.

It's worth noting here that the "plan" at the time was something called "Operation Trinidad", named for the location in southern Cuba where the exile force was supposed to go ashore. Here's the operational map:

Military operations, like real estate, depend on "location, location, location". The Trinidad location made a huge difference in the plan, both for the invasion itself and the supposed subsequent hold-a-piece-of-Cuba-as-"free-Cuba" post-invasion part.

For one, the little city was hard to reach from the main FAR bases and FAR/MNR assembly areas. As you can see, only two roads ran into town, both from the less-inhabited eastern parts of Cuba.

The city was also largely cut off by high ground to the north and west; this made defending it simpler, and provided an escape into the Escambray Mountains - where Fidel and his boys had hid out, and emerged to take the island in 1958 - if things went sideways.

The JCS report was...problematic. Afterwards, MG Gray (who headed the analysis team) said that when his group wrote "...timely execution of this plan has a fair chance of ultimate success..." that by "fair chance" he actually meant "fair" on the scale of great-good-decent-fair-poor...meaning that "fair" meant only about 30 percent.

That never made its way into the group's heads; the report was read as positive and optimistic about success.

This meant that the operation pushed forward, and that the CIA needed as many Cuban fighters as possible. Of the some 1,500 guys who would go ashore in April about 900 were recruited between January and D-Day.

Who were these guys?

Obviously, Cuban. Lots of young guys, originally, former soldiers or students - the kind of young man who historically has always gone for a soldier. The 1961 crop tended to be older, though; family men, including professional types like lawyers or accountants.

Obviously some were batistianos; nothing succeeds in making political enemies like getting your caudillo overthrown. But many of the brigadadistas had left Cuba after the revolution; some because they were former elites or scions of elites who had their wealth expropriated or otherwise knocked down a peg by the revolutionaries. Some had been true liberals or democrats who were appalled by the increasingly soviet turn of the Castro bunch.

All of them had some sort of axe to grind against Castro, and saw the Brigade as the best way to swing it. Many, probably most of them, seem to have known they were being used by the Yanquis. It was hard to imagine anyone with two brain cells not recognizing that.

But they had the same goal as their CIA masterminds, so why not let the rich Americanos help them get what both of them wanted?

Red Hot and Rolling

By February everyone involved in the operation was cruising along, especially in the incoming Kennedy administration. Rasenberger (2011) explains why the operation was so appealing to the New Frontiersmen:

"...the CIA's capabilities comported perfectly with the new president's strategy for waging the Cold War...the CIA got it: victory against Communism would be won not by threatening nuclear obliteration or by engaging in mealymouthed diplomacy, but by prevailing in far-flung regional conflicts where communism was gaining ground. The Congo. Laos. Vietnam. Cuba. Here the means of victory would have to be surgical, shrewd, and, very often, covert."(p. 123)

I presume I don't have to go into the fundamental error of seeing the post-colonial struggles of the Third (and parts of the "Second") World as "communism...gaining ground", but to understand they why and what not only of the Bay of Pigs but of all the stupid things the U.S. did in the Fifties and Sixties (and much of the rest of the 20th Century...) you need to see the world as these Cold Warriors saw it. These weren't locals pissed off at the British or French or Portuguese. They were commies, and their strings were being pulled by Moscow, or Beijing.

To make things more difficult for this particular operation, the Kennedy administration was beginning to have internal communications problems.

Rasenberger (2011) spotlights this particularly in a discussion of a February White House meeting about the project. After Dulles and Bissell briefed the group, which included Kennedy, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Secretary of Defense McNamara, and chairman of the Joint Chiefs GEN Lemnitzer.

After the plan briefing Rusk brought up what he saw as potential problems even if the operation ran on rails. The political fallout could be horrific; America the Bully of the Caribbean, anger and accusations of imperialism from the Eastern Bloc, horror and shame from the Nonaligneds, embarrassed silence from the allies. He didn't come down hard against it, though, or suggest alternatives, just a lot of "concern".

The surprising thing is that neither McNamara nor Lemnitzer said anything. McNamara knew he knew nothing military, so that's one thing.

But Lemnitzer talked afterwards about his reservations. Why didn't he speak up when he had the president's ear?

Rasenberger (2011) suggests several possibilities. Bureaucratic; this was a CIA operation, and perhaps Lemnitzer was constrained by not wanting to seem to try and be the boss of them.

Another was that Lemnitzer had been used to dealing with Ike, whose military experience was greater than his military chief's. Perhaps the CJCS thought that his new boss, like his old boss, could see the problems for himself.

But Kennedy's "military experience" was that of a junior officer running a speedboat, not the general officer in command of an entire theater of war. He needed Lemnitzer's experience...and didn't get it.

Instead, Kennedy seemed to have his own concept of operations. He suggested that this force be slipped in quietly and assemble in the Escambrays, instead of kicking in the door with an American-made boot - in other words, the original "guerrilla force" plan that was already deader'n shit. Kennedy seemed to return to this idea several times, suggesting either his own wishful thinking or the planner's failure to get their boss to understand what they were proposing.

And, remember, Kennedy was still not the actual "president"; he wouldn't be inaugurated until March.

And in March, as president, Kennedy was confronted with the same choices.

In a meeting 11 MAR Kennedy got the update on Operation Trinidad. Bissell provided the shiny upside, the JCS the muted downside (the JCS assessment advised that surprise was essential for success of the pre-invasion airstrikes, but that the odds against achieving surprise were 85% against). The CIA team made the push for how their big shock-and-awe invasion would topple the commies.

Kennedy said no.

"Too spectacular." he told Bissell. "It sounds like D-Day. You have to reduce the noise level of this thing." Bissell started to interject, but Kennedy cut him short. The bigger the invasion, the more American it would appear. Tone it down, he told Bissell, and come back in a few days with a new plan (Rasenberger, 2011, p.138)

This is where I hope that had I been his platoon sergeant I'd have told Kennedy to go pound sand.

The whole operation depended on "spectacular". Once the change had been made from the original guerrilla/maquis infiltration the invasion had to go big or go home. Kennedy made it clear in March that deniability was more important than military success if success depended on going big.

Bissell should have wrapped the entire operation before the end of the meeting.

Instead he and his team went back to the planning table.

The Plans change AGAIN

The bare minimum for success of the operation was a landable beach with an airstrip close enough to secure on D-Day. The airstrip was critical, because the idea was that the FAL B-26s would immediately start operating from there, to back up the story that this really was just a bunch of Cuban patriots, no Yanquis to see here, nope, not a one.

The CIA team found such a place to the west of Trinidad in Matanzas province. The main feature was a narrow deep bay, the Bahia de Cochinos. The beach immediately to the east, Playa Giron, was close to an airstrip long enough to handle a B-26.

The whole area was surrounded by a nasty swamp, the Cienaga de Zapata, that would hopefully provide the same sort of barrier to Castro's forces that the Escambrays had for Trinidad.

The only problem was the name: Bay of Pigs.

The CIA chief of propaganda wasn't happy: "How can we have a victorious landing force wading ashore at a place with that name?"

On 15 MAR Bissell and his team returned to the White House, presented the new Operation Zapata, and were told that a dawn landing was still too much like D-Day. It had to look guerrilla-y, so the ships had to be gone by daylight.

Back to the plans.

On the following day Bissell presented the new night landing plan, only to now hear Kennedy wondering whether the airstrikes that were part of the operation were really needed. Yes, absolutely, Bissell and his team repeated, but Kennedy, according to Bissell, "wouldn't take yes for an answer." (Rasenberger, 2011). The new president seemed fixated on the "guerrilla" idea, but nobody could get it into his head that moving the beachhead 100 miles from the mountains made that utterly impractical.

It's worth reading the Rasenerger (2011) account to get the flavor of the mess of counter-crossing ideas and half-ideas that filled the Kennedy White House, the Pentagon, and the Agency between mid-March and mid-April of 1961. The CIA project team was unwilling to let go of it's baby, the Joint Chiefs were unwilling to be forceful about their reservations, Rusk at State - who Rasenberger quotes as having "admitted that he knew the plan to invade Cuba would not work." - wouldn't go beyond cryptic veiled criticisms.

The official explanation is "groupthink" as it's described in the 1972 book of the same name. According to the author what happened was "concurrence seeking". Everyone involved in the project wanted it to succeed. Nobody wanted to be the Gloomy Gus.

The only person who spoke up strongly against Operation Zapata was Senator J. William Fulbright, chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, who Kennedy told of the plans on a 30 MAR flight to Palm Beach purely by happenstance.

And Fulbright made the tactical error of couching his objections in ethical and legal terms. These were the cowboys of the New Frontier; they were Men of Action, the guys with brains AND balls - they weren't going to be stopped by handwaving about morality and law.

So the operation rolled on through into April.

By the first week of April the revised plan was getting some flourishes. A maskirovka bit where "defecting" Cuban pilots landed in Florida on the day of the first airstrikes to prove the strikes were an inside job. A diversionary landing at another south coast beach to confuse the defenders and draw strength away from Playa Giron.

In Cuba, Castro fulminated constantly about the immanent arrival of the American-paid "mercenaries" through the first weeks of the month. The Policía Nacional Revolucionaria were busy rounding up anyone suspected of not loving the revolution. Many were jailed. Some were executed. The internal resistance - which was supposed to rise when the brigadistas swarmed ashore - was hammered down hard.

The final White House meeting took place 12 APR.

Earlier in the day President Kennedy had answered a press briefing question about how far the U.S. would go to help an anti-Castro rebellion or exile invasion with the following:

"I want to say that there will not be, under any conditions, an intervention in Cuba by the United States armed forces. The government will do everything it can...to make sure that there are no Americans involved in any actions inside Cuba." (Rasenberger, 2011, p.181)The meeting that evening touched again on the importance of airstrikes; two sets, the first on D-2, and again on D-Day. Apparently this had something to do with Bissell's hearing from his military people that some of the Joint Chiefs were lukewarm on the subject.

The discussion went back and forth but supposedly simply petered out. Kennedy never gave an official go order. He did ask what his deadline was to no-go, and was told the noon, 14 APR was the last chance to cancel the D-2 strikes and noon 16 APR to call off the invasion.

Two days later Kennedy met with Bissell for a last chat about the plan. The invasion "fleet" had finished loading and sailed from the port of embarkation, Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, that day, and Bissell was there to give Kennedy a final update on the operation now in progress.

During the discussion Kennedy - who apparently either didn't know or was unsure - asked Bissell how many B-26 aircraft were tasked for the airstrike the next day.

Sixteen, replied Bissell.

That seems like too many, said Kennedy. Cut numbers, make the strike more "minimal".

Bissell didn't ask what "minimal" meant and Kennedy didn't explain, so Bissell cut the number of aircraft in half.

So only eight light bombers took off from the airfield in Nicaragua in the dark of 15 APR to fly their bombs and missiles to Cuba.

The Engagement:

D-2: Air Attacks

The military actions that comprise the "Bay of Pigs Invasion" begin with the airstrikes on 15 APR, D-2. These included three groups of a toal of eight B-26 bombers.

"Gorilla Flight" included two aircraft and targeted Antonio Maceo airport in Santiago.

"Linda Flight" was composed of three aircraft and was directed towards San Antonio de los Baños military airfield south of Havana.

"Puma Flight" included three aircraft and targeted Campo Libertad military airbase.

A ninth aircraft had a special mission that we'll discuss after the bomb damage assessment.

The strikes went in around 6:00am Cuba time, and all eight aircraft unloaded their weaponry; each had been armed with ten 250-pound fragmentation bombs and 5-inch rockets. As we've noted, all eight had a battery of eight .50 caliber machineguns fixed in the nose which were designed for ground attack.

All the targets were "serviced", with Gorilla Flight's bomb-damage assessment (BDA) of 100% of the aircraft on the ground at Maceo airport leading the FAL groups. Linda Flight's 75% at San Antonio was next, while Puma Flight - the only group with lost an aircraft to ground fire - reporting only 50% at Campo Libertad.

Another of the surviving seven FAL attackers - Puma One - was damaged, however, and had to run north to make an emergency landing in Florida. The remainder of the strike group returned to their airfield in Nicaragua.

Interpretation of U-2 post-strike photos, however, reduced the BDA to no better than 50% overall, meaning that something like seven operational military aircraft were still available to the FAR on D-1, including, most dangerously, at least two Sea Furies and three or four of the armed T-33 jet "trainers".

Despite this, no additional strikes were authorized on 15 APR.

D-2: Sea Retreats

The other operation planned for D-2 was the diversionary landing by the Diaz group that targeted the far east of Cuba, about 30 miles east of Guantanamo.

This, in a sort of prescient warning of what would happen over the next week or so, turned out to be an utter bumblefuck. The insurgent group that was supposed to guide the invaders into shore managed to drop a live grenade at their own feet and blew themselves up, wounding several, and scattering the rest.

Then the Santa Ana freighter carrying Diaz and his gang wandered around looking for and not finding the beach, losing several of the small boats intended for the actual landing in the process. Finally the Santa Ana turned back out to sea before dawn.

D-2: A Not-So-Cunning Plan

Remember, the critical element in this whole operation was convincing the outside world that the invasion was 100% Cuban-vs-Cuban. To do this the ninth FAL B-26, #933, flew to Miami Airport and landed claiming to be a defector from the Castro FAR who had taken part in the attacks that morning.

To add a dab of realism one of the engine cowlings had been removed, shot full of holes, and replaced. The pilot, one CPT Zuniga, then killed that engine before landing. So dramatic! The press were invited to report the story of the brave Cubans who had risen up - literally, in their aircraft - against Castro. Zuniga had been tapped for the mission because he was a personable guy and quick on his feet, and he did a decent job of telling his tale.

But here's where the CIA's fuckups bit them and the operation on the ass.

Despite their now-typical failure to understand or report sensibly on military matters, many reporters in 1961 had seen something of the elephant between Korea and WW2. So the boys on the bus noticed that the nose guns were still taped over the way they'd be in the hangar to keep schmutz out of the barrels.

Another guy, who had bothered to learn about Castro's FAR, couldn't help but wonder where the rear turrets on this B-26 had gone, and why it was a "C" model with all the guns in the nose and not a "B" with a glassed-in nose and wing guns?

As any high school kid who's tried to lie his way out of trouble knows, the secret to a lie that will fly is keeping it simple and avoiding any obvious contradictions.

B-26 #933 was a huge metal contradiction, and it not only failed its mission but had long-term effects on U.S. diplomacy, as we'll see.

D-1: A Whole Lot of Nothing

There seems to be some confusion regarding what the Cuban FAR did after the strikes of 15 APR. In later speeches and statements about the events Castro claimed that he did what anyone other than Douglas Fucking MacArthur would have done knowing that an enemy air attack might happen at any time; dispersed his flyable aircraft all over the place so they couldn't be destroyed easily.

Rasenberger (2011) says, however, that the U-2 photos showed that the surviving FAR aircraft were "clumped together at San Antonio de los Baños, making them easy to destroy." He also says that "follow-up strikes...on the afternoon of April 15 had been scrapped...(t)hen came news that there would be no strikes on April 16...either."

Here's the thing about that.

If there had been afternoon strikes, or follow-on strikes planned for D-1, you'd think that 1) there would be some mention of them in documents of the time, and 2) there would also be a record of who "scrapped" them. Given that the U.S. military chain of command knew by 0900 Washington time of the corrected BDA you'd think that there would not have been a military reason for cancellation. Rasenberger (2011) doesn't record a political decision to scratch the strikes on either D-2 or D-1, and the National Security Archive "chronology" mentions only the 16 APR decision (which we'll discuss in a bit) to scratch the D-Day morning strikes.

So were there more strikes planned for D-2 and D-1? And, if so, who "scrapped" them?

I can't imagine that the CIA planning team would; Bissell was adamant about the importance of air superiority over the invasion beaches, and his team was solidly behind him on that.