Brandywine Date: 11 SEP 1777

This one is purely personal.

As a battle it's just another one in the series of "The British beat George Washington in a big stand-up engagement but it doesn't matter because his army isn't destroyed" fights that characterized the "middle colony" phase of the war between the summer of 1776 and the spring of 1778.

Yes, it was "big" - the combined forces engaged were the largest the two sides ever brought to battle outside the Battle of Monmouth the following year. But there's nothing "decisive" about it; indeed, it's probably as "indecisive" as you can get in a conventional fight where one side is comprehensively whipped.

The British beat the shit out of Washington's army and ran it off the field...and then spent the rest of 1777 and the first part of 1778 chasing the damn rebels around southeastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey and still got nowhere. The little bastards were harder to kill than roaches.

Nope, the entire reason you're reading this is because...

...that's where I lived in the Sixties, from just before preschool to about fifth grade.

It's a really spendy 'burb now, but in 1963 or so, when my father the Master Chief and The Busty Redhead his wife had a house built there it was just a road through an old farm field, as it had been for most of the preceding 186 years - during which time someone named Michael Gregg lived down at the eastern foot of the hill.

He (and, presumably, some sort of family along with him) had been there for the preceding twenty-four years or so, probably subsistence farming along with some sort of grazing, across the low "round hill" to the west.

That particular year?

Didn't go so well for him.

Gregg, who was a member of the Kennett Square Friends meeting, had 200 acres on Round Hill Road (his address is listed as what is now the first house to the west, off what is now Kaolin Road). He reported that his crib was looted by the goddamn Brits and their Hessian flunkies some time around the big fight on the 11th.

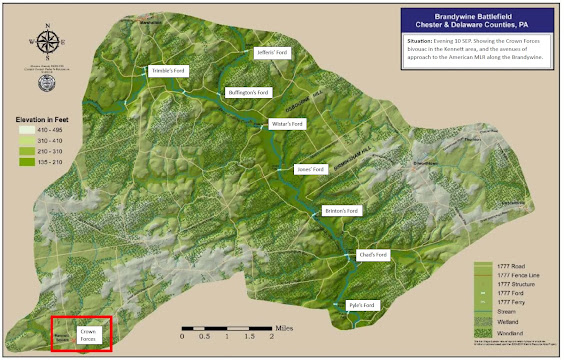

That makes sense; Kaolin is one of the north-south roads between the area around Newark, Delaware and the Kennett area where we know the Crown forces bivouacked on 10 SEP. We know that Howe's force skipped left - north - -between 9 SEP and the following day, and we can track roughly how they traveled by doing the spade work in the tax records of the area as well as the Quaker - "Friends" - meetings.

Quakers weren't supposed to be involved in wars and rumors of wars, and they were encouraged to be above and ignore the activities of those vulgar heathens running around with guns.

But in some cases - where the ammosexuals did them the dirty - Quakers would report the loss to their meeting.

Here's how the day's events are described by Planning Commission (2020):

"In the dark of night on September 10, Gen’l Cornwallis’ Division struggled to make its way through the difficult Red Clay Creek valley terrain. There were no established roads in the area by 1777, so their route was likely via farm lanes and by-roads.

Their route seems to have closely followed modern Chandler’s Mill Rd., which may have once been a farm lane. They descended to the likely fording site from modern Chandler’s Mill Rd/Kaolin Rd juncture. After fording, they directly ascended uphill past the Michael Gregg House to the 1720 Road (modern Kaolin Rd) on a trace. As such farms lanes or by-roads were never dedicated as official roads, they are termed ‘traces’."

We'll never know exactly what happened.

But at some point it seems likely that Crown troops - perhaps a foraging party, perhaps one or more of the left flank security teams - crossed over the field behind my old house where I used to chase the dog or play hide-and-seek in the tall summer grass.

Long before I ever dreamt of soldiers or soldiering, the soldiers came, and passed by my childhood home. Probably in the way soldiers have since Sumer; heavily laden with the impedementia of the column of march, probably sweating and grumbling in the sultry early autumn night while tripping over unseen obstacles in the uneven fields and cursing the genius who thought it would a good idea to climb this fucking hill on the way to and from the middle of fucking nowhere.

So.

This is your battle for April.

Forces Engaged: Kingdom of Great Britain, Scotland, and Ireland (Crown Forces)

The outfit that headed north towards Kennett that night included a varied mix of British Imperial troops - which is to say a mixture of English and Scottish units (containing a lot of Irish troopers) - colonial recruits ("Loyalist" Americans), and contract soldiers from various German states.

The Crown force was divided into two wings, an all-arms grouping that fifty-odd years later would be called a "Division" or, if larger, a corps.

The Division that would become the British "left" wing or maneuver element on 11 SEP consisted of the following:

Cornwallis Division (Left Wing) - five infantry brigades plus a small cavalry and artillery element.

Divisional Troops:

16th Light Dragoons (2 squadrons x 100, 200 all ranks)

(The 16th - and 17th, who were with Knyphausen's Division - Light Dragoons were all the cavalry Howe could scrape up. That was a problem, as we'll discuss later on.)

Hessian and Anspach Jäger Battalion (500 all ranks)

Mounted Jägers (1 company) (100 all ranks)

(Note: these troops were German light infantry, "jägers" in the original German. We discussed this terminology before; the term literally means "hunter" but by the 18th Century effectively had become the military term for light infantry.

In his report of 10 OCT 1777 MG Howe calls them "chasseurs", the French equivalent term. This has been transmitted in some accounts, but given the provenance of the units I suspect this is a linguistic peculiarity of Howe's and that the troops would have called themselves the former.

The other possibility is that the mounted unit alone was informally called "Chasseurs" - the breakdown in Fyers (1930), while otherwise unsatisfactory regarding the Hessian organizational breakdown, lists "Hessian" and "Anspach" Jägers but "Hessian Chasseurs" - which might explain the confusion. I'm honestly not sure.)

A general note on "Hessians": The American rebels liked to call the German troops serving the British Crown in America...

1) "Hessians", despite the fact that the German states that contributed the some 40,000 troops to the colonial rebellion-suppression campaigns included Hesse-Kassel, Hesse-Hanau, Brunswick (including two Hanoverian family dukedoms, Brunswick-Lüneburg and Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel), Aspach-Bayreuth, Hanover (original seat of the Georges, remember?), Waldeck, and Anhalt-Zerbst...and,

2) "mercenaries", despite the fact that the German soldiers were not recruited as paid-to-fight individuals in the sense we think of (or the people in the 1770s thought of) as "mercenaries". Many of them probably enlisted due to the paycheck (sad as it would have been for a private...) but they enlisted not as a paid soldier of Great Britain but as a sworn soldier of Hanover or Waldeck whose prince (who might be the British king, mind...) commanded him to fight in the Americas and whose orders he was following.

Artillery (4 x 12-pound cannon, 6 x 6-pound cannon, roughly 150-200 all ranks)

(I'm having trouble breaking these units down. I believe that the 6-pound cannon might be crewed by a German unit, either from Anspach or Hesse-Hanau, but I can't find anything to support that. McGuire (2006) says this entire unit was Royal Artillery.

So I'll buy that the heavy artillery were British regulars. The Royal Regiment of Artillery raised a "4th Battalion" for service in America. There appear to have been ten "companies" - what as a modern redleg I'd call "batteries" - total, of which Companies 1 through 4 are listed as serving at the Brandywine. Four 12-pound cannon is effectively a battery, albeit a small one, but which battery this was I'm not sure.

Also note that each infantry brigade would typically have had several - 2 to 4 - light - 3-pound or so - cannon "infantry guns" that wouldn't have had Artillery crews; we'll discuss them below.)

Guards Brigade: (This outfit appears to have been raised in 1776 for foreign service from the Household troops in London based on a small group from each of the three foot guard regiments - Schenawolf (2013) says "fifteen privates from each of the sixty-four companies of Foot Guards" and that the assigned strength at the time of embarkation was 1,092; 30 officers and 1,062 other ranks.

Schenawolf (2013) reports that the unit was reorganized when it arrived in North America prior to the Battle of Long Island in August 1776:

"General William Howe ordered they be formed into two battalions of five companies each. First Battalion: 1st, 2nd, 3rd, infantry companies, (men and officers from First Guards regiment), 4th company, (men from all three regiments, officers First Guards regiment), and the grenadier company, (men from all three guard regiments). Second Battalion: Companies 5 & 6, (men and officers from Third Guards regiment), companies 7 and 8, (men and officers from the Coldstream Guards), and the light infantry company, (men and officers from all three regiments)."

Unfortunately I cannot find an order of battle that mimics this detail. The overall reorganization appears similar, but the companies are named for their captains rather than numbered. The assigned strength - unsurprising for a force on active service after more than a year's campaigning - had been reduced to 939 all ranks:

1st Battalion (488 all ranks)

Grenadier company (124)

Hyde's company (93)

Wrottesley's company (91)

Cox's company (90)

Garth's company (90)

2nd Battalion (451)

Light company (96)

Stephen's company (88)

Murray's company (89)

O'Hara's company (87)

Martin's company (91)

(Note the size of the "companies"!

A typical British foot regiment of the 1770s - and keep in mind that a British "regiment" was usually one battalion - was (I believe) authorized up to 1000 all ranks in ten companies (eight "center" or line companies, plus one each light and grenadier company). You'll remember our discussions of Lexington and Concord and Bunker Hill that the typical assigned strength, however, was seldom even half that; companies were more often the size of a modern infantry platoon, around 30 to 40 troopers. But these guys? Nobody below the high 80s and the grenadier company over 100!

But that's "Guards" for you. The Foot Guards got the goodies in more ways than one, and more soldiers was just one of many...)

Light Infantry Brigade: (1,300 all ranks)

1st Light Battalion (650?)

Light companies of (from left to right in formation in 11 SEP) 5th, 15th,

22nd, 27th, 33rd, 38th, 42nd, 35th, 28th, 23rd, 17th, 10th, and 4th

Regiments of Foot.

2nd Light Battalion (650?)

Light companies of (from left to right in formation) 37th, 43rd,

45th, 49th, 55th, 63rd, 71st, 64th, 57th, 52nd, 46th, 44th, and 40th

Regiments of Foot.

(So these "flank company" composite battalions were a Royal Army thing during the entire Revolutionary War - we saw them in Lexington and Concord, remember? They seem to have been the first step towards the eventual "light infantry" revolution completed by Sir John Moore in the late 1700s to provide the British with battalion-size units capable of more complex open-order tactical evolutions than the stolid "center"-company based regiments.

Note that if you divide the total strength (1,300) by the number of companies (26) you get exactly 50 troops per company. I doubt that was the case, but short of digging hard into the morning reports from each individual unit - assuming they still exist somewhere in the Horse Guards or the Imperial War Museum or some long-dead Georgian adjutant's personal papers FFS - breaking the unit strengths down more accurately isn't practical.

It's also interesting to note that these and the grenadier composite battalions included elite companies from regiments not present at Brandywine as a whole, such as the 37th and 43rd Foot. I assume this is because these elite battalions were effectively standing organizations and not thrown together for the Philadelphia Campaign, so their flank companies marched with their elite battalions while the rest of the regiment sat around pulling details in the motor pool, or buffing the billets floors or something.)

Grenadier Brigade: (1,400 all ranks)

1st Grenadier Battalion (755?)

Grenadier companies of (from left to right in formation on 11 SEP) 5th,

15th, 22nd, 27th, 33rd, 37th, 40th, 38th, 35th, 28th, 23rd, 17th, 10th,

and 4th Regiments

2nd Grenadier Battalion (645?)

Grenadier companies of (from left to right in formation) 43rd,

49th, 52nd, 57th, 64th, 71st, 63rd, 55th, Marines, 46th, 44th, and 42nd

Regiments

(Same problem here; we just have overall numbers for the brigade.)

Note that the grenadier companies - befitting their role as the shock unit of the line battalions - are a bit larger (about 53-54 guys per company) than the light infantry. Again, the exact division is 1,400/26 or 53.8 troops per company, kinda hard on the 0.8th of a guy, so the actual strengths varied from probably high to low fifties, but it takes more time and money than I have to find out.)

3rd Infantry Brigade (1,500 all ranks)

15th Regiment of Foot (350-400)

17th Regiment of Foot (350-400)

42nd Regiment of Foot (350-400)

44th Regiment of Foot. (350-400)

(Again, I don't have a breakdown of battalion strengths, but if the typical company strength ranged between 35 and 40 an average regimental strength of 375 comes out close to the reported brigade strength. Assume the usual minor variations between battalions, and remember that all of these units were missing their light and grenadier companies, so just the eight "center" companies. Same for the other three British infantry brigades, below.)

4th Infantry Brigade (1,500)

33rd Regiment of Foot (350-400)

38th Regiment of Foot (350-400)

46th Regiment of Foot (350-400)

64th Regiment of Foot (350-400)

(As above)

Hessian Grenadier Brigade (1,300 all ranks)

von Linsing Grenadier Battalion (400-450)

von Minningerode Grenadier Battalion (400-450)

Lengerke Grenadier Battalion (400-450)

(These units were, like the British Light and Grenadier battalions, formed by detaching the grenadier companies from the line ("fusilier") battalions. Just to give you and example, the Minningerode unit was made up in January 1776 by pulling the grenadiers from the Erbprinz, von

Ditfourth, von Lossberg, and von Knyphausen battalions. Linsing seems to have been similarly amalgamated but more elite; it included companies from the Hesse-Cassel Leib unit (the bodyguard) and the Garde units.

Knyphausen's Division (Right Wing) - three infantry brigades plus cavalry and artillery

Divisional Troops:

16th Light Dragoons (2 squadrons, 200 all ranks)

(As the 17th LD above. It's interesting that Howe split his cavalry despite his task order to his Right Wing largely precluded any useful role for cavalry.)

Queen's Rangers (300)

Rifle Corps (90)

Both of these infantry units were "loyalist", American colonists serving the Crown. The "Rifle Corps" was the famous (or infamous, if you were a rebel) "Ferguson's Rifles")

71st Foot (1,200 in three battalions)

(Known as "Fraser's Highlanders", this oversize unit is not the same as the 71st Foot that eventually became the "Highland Light Infantry" of the Peninsular War.)

Artillery: (6 x 12-pound cannons, 4 x ?? howitzers, probably about 150-200 artillerymen)

(The artillery for Knyphausen's Division is specified as coming from the batteries attached to 1st and 2nd Brigades, so Royal Artillery and as such see the divisional artillery above. Difficult to guess how the guns were divided; 3 cannon, 2 howitzers per battery? Seems too tidy, but hard to say anything else...)

Hessian Brigade: (2,000 all ranks in three battalion-sized regiments)

Erbprinz Infantry Regiment

Donop Infantry Regiment

Mirbach Infantry Regiment

(The Erbprinz unit was raised in Hesse-Hanau; the other two in Hesse-Kassel.

The information I can find on the web suggests that the Erbprinz Regiment consisted of a single battalion of five line (musketeer or fusilier) companies and a grenadier company with an authorized strength of about 100 all ranks, so 600 or so for the regiment. Remember that the grenadiers had been detached, so that leaves the five line companies that were presumably below authorized strengths...but if the three units were similar that leaves us with about 500 German soldiers unaccounted for.

So my guess is that the Hesse-Kassel units were larger; figure about 500 for Erbprinz and that leaves 750-odd for each of the other two, which isn't unrealistic for an 18th Century infantry battalion.

1st Infantry Brigade: (1,400 all ranks in four battalions)

4th Foot (~350?)

23rd Foot (~350?)

28th Foot (~350?)

49th Foot (~350?)

(These numbers seem on the small side, but it's possible that the reason these two brigades were assigned to the fixing force was just for that reason. Worth noting here that the 4th of Foot ("King's Own") had been fighting rebel Americans since April 1775 alongside another of the units in this brigade, the 23rd of Foot.)

2nd Infantry Brigade: (1,300 all ranks in five battalions)

5th Foot (~250?)

10th Foot (~250?)

27th Foot (~250?)

40th Foot (~250?)

55th Foot (~250?)

(Same as above.)

So approximately 14,800 infantry, 400 cavalry, 400 artillery (10 x 12-pound cannon, 6 x 6-pound cannon, 4 x field howitzers of some type) under General Sir William Howe.

Forces of the Continental Congress (in rebellion against the Crown):

Let's call them "American" or "Continental" troops just to save time, although I suspect that there was some considerable disparity over what to call them and what they called themselves.

Unlike the two earlier engagements we talked about, this was clearly not just a bunch of angry civilian rebels or armed native militiamen, an 18th Century gaggle of Proud Boys. These were "rebels in arms", closer to the Parliamentary armies of the 17th Century civil war. Many of them surely thought of themselves as "Englishmen" who were there to fight "royal tyranny" much as their Roundhead ancestors had.

The "American" forces were largely organized by Divisions, although unlike the Crown's "grand divisions" the rebel army "divisions" are closer to the purely-infantry divisions of the American Civil War.

Army troops:

4th Continental Artillery Regiment: 1 x 6-pound gun, 2 x 4-pound guns, 1 x 8-inch howitzer plus another 10 pieces of unknown caliber and type, and probably 400-500 artillerymen.

(So "Proctor's Battery" is the only artillery organization I can find detail for; those are the three cannon and the howitzer listed first that were posted at Chad's Ford.

The Wiki entry for "4th Continental Artillery", however, says that an additional four-gun battery was dug in at the ferry south of Chad's, and a two-gun redoubt dug in east of Brinton's Ford to the north.

In addition to these ten pieces GEN Howe's after-action report says that his force captured 11 of the 14 guns that started the day in American hands...so there's that. Where the other four guns were, what they did, and whether they were part of the guns lost that day, I have no idea.)

Light Infantry (~700 all ranks?)

(This truly was an ad-hoc organization, formed at the beginning of the campaign by culling a mixture of regular grunts armed with muskets and hunters and frontier riflemen.

This role had until the summer of 1777 been filled by the Daniel Morgan battalion of riflemen, but this unit had been sent north to deal (and did deal) with Burgoyne's force. When Howe moved out Washington directed his seven brigadiers to send about 100 guys to make up a replacement unit. Neville (2018) says that Montresor reports that not "...all of the brigades actually provided troops,

however, and the new corps was evidently dominated by Virginians." The returns from 3 SEP list the light battalion at 800 assigned, up to 900 including officers (Harris and Ecelbarger, 2021)

This unit had seen hard fighting at Cooch's Bridge on 3 SEP, however, and may have lost something close to 50-100 killed, wounded, or captured, so my guess is that the actual present for duty on the morning of 11 SEP was well below 800 and might even have been below 700...)

Chester County Militia (~100-300? in small units)

(A highly amorphous group of odds and sods from the local rebels-in-arms were very loosely attached to Continental Army but spent most of the day spread out to the west of the Brandywine poking around scouting and making themselves obnoxious; this includes outfits like "Dunlop's Partizan Rangers" of which we'll hear quite a bit more in a moment. I can't even find a reference to who and where these guys were, but they were out there skulking about all morning...)

Continental Light Dragoons (500 all ranks?)

(I'm really in the dark on this unit.

The first American cavalry unit was raised in Virginia in June 1776 as the "Light Horse" of six troops of roughly 35 all ranks each, so 210 in the regiment. The unit was accepted into the national army as the "1st Continental Light Dragoon" regiment. A "2nd Continental Light Dragoon" unit was organized in Connecticut in December 1776, a 3rd Light Dragoons were raised in the Jerseys, and a 4th Light Dragoons in Philadelphia, both in January 1777.

All four of these units are recorded as having been present at the Brandywine.

A cavalry reorganization in March of 1777 authorized a strength of 280 for each regiment plus a headquarters troop of a dozen or so, suggesting that at full strength four dragoon regiments should have fielded something like 1,100 to 1,200 troopers.

But the Continental Army strength returns analyzed by Harris and Excelbarger (2021) report a total of 497 dragoons present for duty in December 1777 and the numbers never rise substantially above 500 for any of the returns between August 1777 and that time.

The correspondence we have during the day of 11 SEP usually refers to COL Bland, the CO of 1st CLD; this makes me suspect that the bulk of the American cavalry was pulled from that unit. But it's entirely possible that there was a hash of five hundred-odds-and-sods from all four regiments, which - as we'll discuss - might explain a lot about the events of the day.)

Nash's (North Carolina) Brigade (1,094 all ranks)

Nine (1st through 9th) NC regiments (~120 each?)

(These dinky little outfits look more like big companies than "regiments", which might explain why they were kept about Army HQ rather than assigned to a division.)

A general note on Continental line units: So one of the most difficult things the pre-Constitution United States had to deal with was that the states weren't very, y'know...united. And that extended to the Army, as well.

Since the Continental Congress had little or no fundraising power, or much actual political authority altogether, the early "Continental Army" was, in fact, a hodgepodge of military organizations authorized, funded (to the extent anything in the revolutionary states were "funded"...), raised, trained, and sent to the active forces by the states.

Initially (and we'll discuss this in depth during the "Campaign" section) the idea was to use short-term enlistments, but events proved that prolematic, so on 16 SEP 1776 Congress changed the terms of enlistment to "for the duration" and established a larger notional force. But the infantry units were still raised through the states, just as "Continental line" units. So there was a "Delaware line" and "New Jersey line" and so on.

And every state did it their own way, from table of organization and equipment to uniforms (assuming they actually provided uniforms...) to how the units drilled. Dunkerly (2021) makes much of this, noting that even the word of command differed, with some states preferring the British manual drill regulations of 1764 (the "Manual Exercise of 1764"), some the French Ordonnance du Roi de 6 Mai 1755, some the Prussian drill manual of 1750. This turned out to be a problem, as we'll see.

A specific note on Continental line units - organization and strengths: So all this confusion and delay caused by having each state come up with it's own version of "infantry regiment" extended to how the regiments broke down.Typically the Continental units mimicked the British in a "regiment" being a battalion, and the battalion formed from companies.

Once you get down to companies, though? Things get pretty random.

A British regiment/battalion was always divided into tenths; ten companies, eight "center" or regular line companies, one light company, one grenadier (heavy) company.

But Continental units didn't want to be all boring and decimal. The 1776 units were supposed to have eight line companies. In 1781 Congress added a ninth, light, company. But everything I've read suggests that the company numbers could range from five or six to ten. And the strengths - authorized 90 all ranks per company, so (with the headquarters element) about 730 per regiment/battalion - were fictional and all over the place, as we'll see below...

Armstrong's (Militia) Division: (~2,000 all ranks)

1st Pennsylvania Militia Brigade: (~1,100-1,200?)

Philadelphia County Regiment (Moor's) (~160-170?)

Philadelphia County Regiment (McVaugh's) (~160-170?)

Bucks County Regiment (Folwell's)(~160-170?)

Lancaster County Regiment (Watson's) (~160-170?)

Berks County Regiment (Hunter's) (~160-170?)

York County Regiment (Thompson's) (~160-170?)

Cumberland County Regiment (Dunlap's)(~160-170?)

2nd Pennsylvania Militia Brigade: (~800-900?)

Philadelphia County Regiment (Smith's) (~160-170?)

Chester County Regiment (Evans') (~160-170?)

Lancaster County Regiment (Greenwalt's) (~160-170?)

Lancaster County Regiment (Lowry's) (~160-170?)

Northampton County Regiment (Udree's) (~160-170?)

(There's a nice little summary of these guys here, but the tl:dr is that these were the real no-kidding "well-regulated militia" of Joe Doakes and his pals from the neighborhood tavern. They were utterly incapable of going muzzle-to-muzzle with Crown regulars, and while Nathaniel Greene figured out how to use them effectively George Washington never considered them more than a sort of nuisance and at Brandywine parked them as far out of the line of fire as he could.)

Greene's (1st) Division: (~2,500 all ranks)

1st Virginia Brigade: (~1,250)

1st Virginia Regiment (~250?)

5th Virginia Regiment (~250?)

9th Virginia Regiment (~250?)

13th Virginia Regiment (~250?)

German Battalion (~250?)

2nd Virginia Brigade: (~1,250)

2nd Virginia Regiment (~250?)

6th Virginia Regiment (~250?)

10th Virginia Regiment (~250?)

14th Virginia Regiment (~250?)

Pennsylvania State Regiment (~250?)

(We'll see this again and again, so it's worth noting here the small size of these "regiments" and brigades. The brigades are more like European "regiments" and the "regiments" closer to large companies. This is, I suspect, an artifact of the way the colonials raised their units. Everyone wanted to be an officer, and (later on) nobody wanted to be there at all, so these units - small to begin with and over-officered - shrank as attrition (illness, injury, death, desertion) wore them down and they couldn't be amalgamated or rebuilt.

So they just got smaller and smaller, and had to be lumped together to be effective. I read that by Yorktown all these Virginia "regiments" together came to something like 700 guys. Fucked up? Sure! But that was the way we Yanks did things back in the day...)

Wayne's (4th) Division: (~2,000 all ranks)

1st Pennsylvania Brigade: (~1,000)

1st Pennsylvania Regiment (~180-200?)

2nd Pennsylvania Regiment (~180-200?)

7th Pennsylvania Regiment (~180-200?)

10th Pennsylvania Regiment (~180-200?)

Hartley's Additional Continental Regiment (~180-200?)

2nd Pennsylvania Brigade: (~1,000)

4th Pennsylvania Regiment (~180-200?)

5th Pennsylvania Regiment (~180-200?)

8th Pennsylvania Regiment (~180-200?)

11th Pennsylvania Regiment (~180-200?)

A note on unit strengths: While I had to rely largely on the internet as well as the army returns listed in

Sullivan's (3rd) Division (~1,700 all ranks)

1st Maryland Brigade:

1st Maryland Regiment (200*)

3rd Maryland Regiment (114*)

5th Maryland Regiment (-) (~40-60? Dunkerly (2021) says "two companies, strength unknown")

6th Maryland Regiment (~180-200)

1st Delaware Regiment (79*) (detached)

2nd Maryland Brigade:

2nd Maryland Regiment (~180-200)

4th Maryland Regiment (~180-200)

7th Maryland Regiment (~180-200)

8th Maryland Regiment (Dunkerly (2021) says "just over 300", so ~310?)

2nd Canadian Regiment (400) (detached)

(Two infantry units - 1st Delaware and 2nd Canadian - were initially pulled out of Sullivan's Division to secure several of the northern fords (the Delaware line at Jones's, the Canadians between Wistar's and Buffingtons. Oh, trust me, we'll talk about that a LOT in a bit...)

Stephen's (2nd) Division (~2,000 all ranks)

3rd Virginia Brigade: (~1,200)

3rd Virginia Regiment (170*)

7th Virginia Regiment (472*)

11th Virginia Regiment (377*)

15th Virginia Regiment (~160-170?)

4th Virginia Brigade: (~750-850?)

4th Virginia Regiment (~160-170?)

8th Virginia Regiment (~160-170?)

12th Virginia Regiment (~160-170?)

Grayson's Additional Continental Regiment (~160-170?)

Patton's Additional Continental Regiment (~160-170?)

Stirling's (5th) Division (~2,000 all ranks)

New Jersey Brigade: (1,060*)

1st New Jersey Regiment (184*)

2nd New Jersey Regiment (310*)

3rd New Jersey Regiment (300*)

4th New Jersey Regiment (266*)

3rd Pennsylvania Brigade: (~970?)

3rd Pennsylvania Regiment (150*)

6th Pennsylvania Regiment (~160-170?)

9th Pennsylvania Regiment (239*)

12th Pennsylvania Regiment (231*)

Spencer's Additional Continental Regiment (186*)

So about 15,000 to 16,000 total, including roughly 14,000-15,000 infantry, 500 cavalry, and about 500 redlegs with 10-14 guns of various calibers under GEN George Washington.

The Sources: The fight along the banks of the Brandywine has all the ingredients for modern reportage outside daily newspapers. The newspapers of the day had yet to discover the "war correspondant".

Both combatant sides were largely literate - at least at the officer levels - and both were the combat arms of bureaucratic states whose governing bodies expected (and demanded) regular reports as well as all the sorts of military bumf - morning reports, casualty lists, expense vouchers, details of combat losses and writeoffs - we rely on to reconstruct military history.

Mind you, the sort of minutiae we expect from modern military recordkeeping was far from fully developed.

There's a terrific example of this in an article from the Journal of the American Revolution from October 2021 by The Numerical Strength of George Washington’s Army During the 1777 Philadelphia Campaign". In this the authors note that

"The multitude of books and monographs dedicated to the 1777 Philadelphia campaign, whether in part or in entirety, estimate American troop strength because no army returns between September 1 and October 4 (the primary period of battles) were known to exist."

Their reporting updates the historical record by including two returns (dated 3 SEP and 24 SEP, so bracketing our engagement...) but note that no modern armed force would consider a three-week lacuna in strength reports to be acceptable by any means. Lacking the sort of instantaneous communications provided by radio, telephone, and now the internet, the 18th Century was not nearly so picky.

Still, numerous primary sources, ranging from hastily scribbled action orders and reports through letter-form accounts to memoirs and personal papers are extant and researchable, and from these a thick hedge of secondary sources has emerged, including official American and British government histories.

For the purposes of this piece, as usual, I'll try and provide largely the sources available on-line.

Internet sources:

Perhaps the first place to hunt for primary sources is the Brandywine page at the "Founders Online" section of the National Archives. This site includes several useful sources, including transcriptions of battlefield communications - and we'll talk about some critical ones, like the Ross, Sullivan, and Bland notes - as well as GEN Washington's sheepish report of the defeat.

The Founders site also has a nice "Editorial Note" that summarizes the primary source information, and includes directions to published primary sources such as the personal papers of Continental commanders such as Greene and Sullivan or Crown officers such as

The "ExplorePAHistory" site has a scan of Washington's original 11-12 SEP after-action report to Congress.

The JSTOR site has a compilation (Fyers, 1930) of GEN Howe's reports to Lord Germain, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, sort of the Georgian equivalent of a cross between a modern US MACOM CINC and a State Department official charged with government policy in a combat zone.

The Mount Vernon site has a summary of Washington's papers concerning the engagement.

Numerous participants published accounts (or left memoirs or journals that were published by others) after the war, including one we've already mentioned,

Chester County Planning Commission & Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc. that I've cited here as CCPC (2020).

I can't recommend this exhaustive study highly enough. The authors' intent is to support a county-level acquisition and preservation of the battlefield and related sites, but in the process they have, for instance, searched the archives of the southeastern Pennsylvania and northern Delaware tax assessors and Friends meetings for reports of things like "depredation" and "suffering" that indicated the passage - and pillage - of the Crown forces.

It's a terrific source for not just the fight itself but the history of the land and people in and around which the fight took place.

The Brandywine Battlefield Park site has a nice straightforward account of the events of the day.

The British Battlefields Brandywine site gives you much the same from the Imperial perspective.

There's a private website run by some outfit called the Independence Hall Association called Virtual Marching Tour of the American Revolution; the introduction to their section on the Philadelphia Campaign is here. I'm cautious; there's no citation links, and when we get to the section on pre-battle intelligence we'll see, there's some odd things going on. Use with care.

For a view from the dinky little state next door there's "The British Invasion of Delaware" (Kauffman and Gallagher, 2013), dedicated to "American courage and optimism", which is pretty cute for the state whose only addition was desultory whipping (Cooch's Bridge) and the current hosting of about a gajillion predatory credit card companies.

Secondary sources include:

McGuire, T. 2006 The Philadelphia Campaign, Stackpole Books, Mechanisburg, PA. You want volume 1, Brandywine and the Fall of Philadelphia.

Smith, S. 1976. The Battle of Brandywine. Philip Freneau PRess, Monmouth Beach, NJ.

These two appear to be the most commonly accepted modern studies. I've got McGuire in digital form; Smith is long out of print, difficult to find (none of the Portland-area libraries hold a copy) and expensive to purchase, which is unfortunate since he appears to be the standard modern reference.

I like McGuire (2006) as a general history. He uses source judiciously but also writes well enough to make the story cohere and flow, and there's some genuine artistry; his description of the advance of the British grenadier regiment is damn near poetic. A good read, and solid history.

I've already discussed this work already a bit, but Dunkerly, R. 2021 Decision at Brandywine, Westholme Publishing, Yardley, PA. is a real bagatelle.

On the one hand Dunkerly has done 1) an amazing, as in "how the hell do you do this?" kind of scholarly work pursuing primary sources for 2) the seminal study of the main encounter of the fight around Birmingham Hill.

As much as we can now know about this moment and this place, he tells us.

That said...ohmifuckinggod is he an fucking awful writer.

Worse, he's got no editor to save him from himself. He repeats himself over and over (and over). His organization, well, isn't - he constantly gets bogged down in criss-crossing quotations and loses the narrative (and since his account is nearly all quotes from participants that makes it ridiculously difficult for the reader to follow what's happening - to the participants a battle is always going to be confusing, noisy, frightening, and seemingly random - it's the historian's job to try and put all those experiences in context for the reader of that history, and Dunkerly is terrible at that).

He also has some big ideas that he introduces with much thunder then wanders away from and fails to support. One of Dunkerly's main theses is that the lack of uniform drill among the Continental units was one of the main causes of the defeat on Birmingham Hill.

That's not entirely incredible; the sort of "military commonsense point-of-view" suggests that should be the case; units that don't train together don't usually fight well together.

But amid all the first-person accounts Dunkerly fails to find so much as a single instance of anyone at the time upset or complaining about or blaming this as the problem or even A problem.

His soldiers stories don't mention anything, commanders' stories don't blame it, not even Sullivan's, who took a shitload of stick for Brandywine and spent a shitload of ink defending himself. Nowhere in his litany of excuses and rationales does Sullivan ever say anything like "well, if it wasn't for those damn Jersey boys and their stupid slow French drill..."

It's a tremendously valuable little book. But for all the good inside the mess makes it kind of a slog to read, and it makes me wish I could have been the guy's editor to make it better. So YMMV.

As the bodices heave and rip...

As far as I know there is no fictional version of the events of September 1777, but for the connoisseur of High Victorian literature that at least takes place nearby I can only refer you to Bayard Taylor's The Story of Kennett.

Stern Quaker daddies, loyal and true young lovers, spiced with the antics of that dashing desperado Sandy Flash (who was, in fact, a real Revolutionary loyalist and robber hanged for being a loyalist, a robber, and a fucking pest), TSoK has got it all. Well, except for heaving bosoms and ripped bodices; I'm not sure where THIS cover version comes from...

...but I guarandamntee you that our boy Bayard would have fainted dead away if he'd seen his daintily modest little Quaker heroine scampering around in that outfit.

So, sorry, that's the closest you're gonna get to bodices, heaving or ripping or any sort of other lascivious writhing in TSoK.

I can't describe it any better than the author:

"In these days, when Fiction prefers to deal with abnormal characters and psychological problems more or less exceptional or morbid, the attempt to represent the elements of life in a simple, healthy, pastoral community, has been to me a source of uninterrupted enjoyment. May you read it with half the interest I have felt in writing it"

The Campaign: So the last time we saw our opponents it was over two years earlier and they were squaring off outside Boston and the colonists were handing their hoped-to-be-former colonial masters a hell of a bloody nose.

That was kind of the rebellion high-water-mark for the next couple of years, though.

The British (and as many of their loyal Bostonian pals that could clamber aboard the 1776-equivalent of "the last helicopter off the embassy roof") sailed out of Boston Harbor in March, never to return. The rebels officially declared that they weren't just regular old British "rebels" - that is, they didn't want to just swap kings or parliaments - but a whole different country in July.

Then that summer the strategic focus of the "northern campaign" moved to the next big port city to the south, New York.

It's a Hell of a Town -

The rebel plan was - since the new American nation lacked any sort of real navy and so couldn't really stop the Royal Navy from moving the Crown forces anywhere with a coastline - to fortify the New York City and vicinity and beat back a British attack after a landing, which happened in July on Staten Island and then in August in Brooklyn.

The two armies met on Long Island on 26 AUG 1776.

There a diversionary element of Howe's force held Washington's army by the nose - attacking up the Gowanus Road in what is today Brooklyn - while the main maneuver element looped wide to the east through Jamaica Pass out on Long Island and fell on the American left.

The Continental Army collapsed to the Brooklyn Heights, from which they had to be Dunkirked across the East River. The Crown forces followed, took Manhattan, and chased the Americans up the Hudson and eventually across the river into New Jersey.

Part of the Americans' problem was getting their ass thoroughly whipped, but another was that, much as their grandkids thought in 1861, many of the rebels thought that the war would be "over by Christmas", so the term of enlistment of many of the units that had been raised for the siege of Boston and then fought in New York were running out.

So along with losses to KIAs and sickness and despair and desertion, lots of perfectly healthy soldiers got to the end of their term, thanked the Continental Congress for their service, and went the hell home.

The Continental Army that went into winter quarters in Pennsylvania was in rough shape.

Back from the brink: Trenton and Princeton -

During the "Ten Crucial Days" - 25 DEC 1776 to 3 JAN 1777 - the American forces first raided the German cantonment in Trenton, largely destroying (mostly though capture or rout rather than killing) a detachment from three regiments (von Knyphausen, von Lossberg and von Rall) and then pushed north against a British brigade (three regiments - 17th, 40th , and 55th of Foot) with cavalry support (16th Light Dragoons) near Princeton. The 1,500-man British force was outnumbered 2-1 and driven off the field.

GEN Howe concluded that fucking with these rebels in the cold Jersey barrens was a mug's game and pulled the bulk of his forces back to around New York City and the north Jersey suburbs for the rest of the winter.

The little victories of Trenton and Princeton might not have been much militarily. But emotionally and politically? They were a straight shot of pure jungle juice; the raggedy rebel soldiers had gone toe-to-toe with German and British professionals and had kicked their ass.

Certainly things didn't look much better from a fiscal or economic viewpoint - the colonies were still fucking broke and facing off against one of the biggest, baddest Empires that ever struck back - but at least there was the hope that the military of the Crown, despite all those redcoats and Hessians and battleships and God knew what else, couldn't just steamroller the rebel armies and start hanging traitors.

Cunning plans: Burgoyne and Howe and Germain, oh, my -

Here's how the Wikipedia entry for "Philadelphia Campaign" describes what the British higher decided to do next:

"...(GEN) Howe proposed to Germain...that (a) British expedition be launched with the goal of capturing Philadelphia, the seat of the rebellious Second Continental Congress. Germain approved Howe's plan, although with fewer troops than Howe requested. He also approved plans by (GEN) John Burgoyne for an expedition (south down the Hudson Valley). Germain's approval of Howe's expedition included the expectation that Howe would be able to assist Burgoyne, effecting a junction at Albany between the forces of Burgoyne and troops that Howe would send north..."

Why the hell Germain expected this I have absolutely no fucking idea.

Burgoyne's force would be pushing south from Canada, Howe's also pushing south through the Jerseys to Philadelphia (at least that was Howe's original proposal). For Howe to turn his forces around and hump up the Hudson, with Washington right behind him ready to slap him a good one? To somehow bail out Burgoyne, way the devil up the river? How the hell could that work?

Germain had a lot of issues - not picking an overall CINC for his North American expeditionary forces was one of the worst - but his spatial and geographic understanding of his colonial area of operations seems to have been another. There's no way any commander who understood the geography of the upper North American colonies and military logistical and operational realities and thought about this "plan" for a moment should have approved it.That's him on the left, BTW, looking appropriately po-faced and cynical.

Then the whole "plan" thing got worse.

Wiki again:

"Howe decided in early April 1777 against taking the British Army over land to Philadelphia through New Jersey since this route would entail having to cross of the broad Delaware River under hostile conditions and likely require the transportation or construction of necessary watercraft. Howe's (revised) plan, sent to Germain on April 2, isolated Burgoyne from any possibility of significant support, since Howe instead would take the British Army to Philadelphia by sea, and the New York garrison would be too small for any significant offensive operations up the Hudson River to assist Burgoyne."

No shit, Sherlock. If the original plan was bold but difficult, the revision was flat-out impossible.

No matter; Germain let his field commanders go do their things. Burgoyne left St. John's, Quebec on 14 June 1777, and Howe sailed from New York City in July.

We talked about what happened to Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne way back in 2008 (Christ, was it really fifteen years ago? God, I'm old.) and we can look back over that if you please.

For now we'll look at what happened to his rival Howe and the chief of his foes, Washington, and the many people in their charge.

Jolly boating weather and a hay harvest breeze -

The British fleet sailed south for nearly a month, first to the mouth of the Schuylkill River in Delaware Bay, where they farkled about noisily for a bit to draw rebel attention, then slipped out again and looped a bit south into Chesapeake Bay. Once in the bay the attackers sailed north into the Elk River at the very head of the estuary where the advance party went ashore on 25 AUG 1777 at a place called "Elk Ferry", pretty much the middle of buttfuck nowhere, Maryland.

The countryside in August was lush and wild; "...a real wilderness..." according to CPT Ewald.

LT Feilitzsch of the Anspach Jagers said it was "A bare woods, here and there a small place with a house and a field, but where not a soul is to be seen." The troops hootched up once ashore but that didn't help much; a series typical late summer storms doused them.

This was trouble. The transport horses had done poorly at sea, and the already-bad roads were mired with the downpours and murder on the horse teams. Montresor reported that the Guards lost a quarter of their basic load of ammunition to the rain, and that the "...road were heavy and the horses mere carrion..."

After three days of foraging and organization the Crown forces were ready to move north, though, first to the little town of "Head of Elk", where they spent some more time foraging and scouting the nearby portions of eastern Maryland and northwest Delaware.

On the way it's worth noting that the behavior of the Crown troops during this time was particularly vicious. Cattle rustling and horse thievery were an accepted part of 18th Century warfare, but "plundering" - looting valuables - wasn't, and there was a lot of that, particularly by the German soldiers. But not only the Germans; one British officer wrote that "A soldier of ours was yesterday taken by the enemy...who had chopped off an unfortunate woman's fingers to plunder her of her rings."

Not that the American troops were idle; Washington sent a nastygram to some of his cavalry (largely foreign volunteers led by one COL Tuffin) about plundering. War usually sucks worst for the unarmed people around it, and the Brandywine campaign was no exception.

Shots fired! Shots fired!: Cooch's Bridge and the Armies Face Off -

Discounting a somewhat comical encounter with some rando Maryland militia outside Head of Elk, the first real notion the Crown forces had that the Americans were nearby in force was just over the Maryland-Delaware border at a place called Cooch's Bridge.

Here, on 3 SEP, elements of the newly-formed Continental Light Infantry Regiment ambushed Howe's advance party, largely Hessian and Anspach Jagers. In a brief fight the Crown light infantry (both the British 2nd Light Battalion as well as the Germans) drove the American light infantry off the ground with loss.

The losses were fairly small - single figures from the Crown lights, possibly 20 to 40 or so Americans - but the defeat caused a fair bit of muttering about COL Maxwell, the Light Regiment commander. For the time being he remained in charge, but many of his contemporaries started giving him the military side-eye.

For the next five days the two sides stood off; the Crown troops near the Cooch's Bridge area and the Americans around the Delaware town of Newport. The Crown forces needed to get around them, the east and southeast was a river, so in the predawn hours of 8 SEP Howe march ordered his force and moved about ten miles north out of Delaware.

The Armies Move: Delaware to Pennsylvania -

Washington's army stood to their arms all day as their commander began receiving reports of the Crown troops moving north and northwest.

The Crown movement was complicated by the steep hills, narrow valleys, and bad roads, as well as Howe's direction to move in separate wings. This movement is described in detail in CCPC (2020):

"Each column was to take a separate route to rendezvous at the initial location of Welch’s Tavern along the...Great Nottingham Road (near modern Longwood Gardens’ entrance on Baltimore Pike). One column, commanded by GEN Knyphausen, which contained the baggage and supply provisions of the army...was to embark on a safer and longer route while the rest of the Crown Force army acted as a screen taking a shorter route."

Primary sources state that GEN Knyphausen’s column commenced their march in the early afternoon. They also indicate that the column’s departure was very slow and drawn out (the rear detachment didn't move out until 1800hrs 9 SEP)

After a few hours of GEN Knyphausen receiving his orders, GEN Cornwallis and GEN Howe, with the main body of the Crown Forces (left) camp on Limestone Rd...turned east on approximately today’s Valley Rd. toward Hockessin.

The march, however, was on “undefined,” “indefinite”, and “bad” roads that proved too difficult for (the) larger Crown Force column. By midnight (9/10 SEP) GEN Howe issued a universal halt and made camp at Hockessin Meeting House. After realizing that it would be impossible for his forces to make it to Welch’s Tavern given the strenuous march, GEN Howe set a plan into motion to rendezvous with GEN Knyphausen in the village of Kennett Square instead.”

But to do that Howe needed to be sure that Knyphausen - and most importantly, the vulnerable baggage and artillery trains - didn't get there first.

GEN Howe then came up with one of those sorts of cunning plans that general officers do; he whistled up his aide CPT Muenchhausen, gave him a force of one LT Knight and a dozen light dragoons, and told them to go out into the rainy night, find Knyphausen, and let him know to hold up at New Garden Friends Meeting, well west of Kennett.

The captain had little choice but to salute and move out smartly. But I'm sure he was thrilled about poking around enemy territory in the dark, and, sure enough, the trip sounds hairy as hell: they rode ten miles - running into rebel cavalry twice but evading their fire and escaping - before finally stumbling across Knyphausen's outfit that was already way down the post road and just west of Kennett.

Well, sod that for a game of soldiers; Knyphausen couldn't turn back in the rain and dark. Muenchhausen recommended he hold where he was and he'd try and find some assistance.

This came in the form of the British 3rd and 4th Brigades. GEN Howe had detached them from Cornwallis' force and sent them to find the Right Wing. First north - where the roads were impassable, then northwest down the road Knyphausen had followed to New Garden, but taking a right at Limestone Road to cut north to the post road. The brigades had a miserable death-march that took them all night and well into 10 SEP.

Here's the best guess that the CCPC mapmakers can come up with:

Meanwhile the rest of Cornwallis' corps was pounding their ears in Hockessin. They had a leisurely wake-up, were on the road about 0500 and pulled up in Kennett at 0900. There everyone fell out and started reorganizing and preparing for what was sure to be a fight the next day.The threat of Howe's force reaching the main Post Road - the modern Baltimore Pike/US-1 - and gaining what we'd call a "high-speed avenue of approach" to Philadelphia had been to dangerous for the American forces to ignore.

In the early morning of 9 SEP Washington's army marched out of Newport and up the east bank of the Brandywine Creek to around Chad's Ford where the post road crossed the Brandywine.

The Continental Army settled in along the east bank, posting pickets at the known fords and beginning some field fortifications at Chad's, about seven miles east-northeast of Kennett.

Both sides knew as the sun set on 10 SEP that the next day would be a busy one.

The Engagement: The U.S. Army's Training Publication ATP 3.21 (The Infantry Platoon and Squad) says this about the "Defense of a Linear Obstacle":

"Linear obstacles such as mountain ranges or river lines generally favor a forward defense. It is extremely difficult to deploy in strength along the entire length of a linear obstacle. The defending leader must conduct economy of force measures in some areas.

The counter-reconnaissance effort is critical when fighting to deny the enemy the locations of the platoon's forward positions. If the enemy locates the forward positions, he will concentrate combat power where he desires while fixing the rest of the platoon to prevent their maneuver to disrupt his attack. This tactic enhances the security mission and deceives the enemy reconnaissance that may get through the security force."

The Continental force drawn up behind the Brandywine Creek didn't have a field manual to consult, but Washington and his officers had been doing this for a while, and they had some sense of what they needed to do.

The Crown forces needed to cross the creek to do them a disservice.

Which meant a bridge - of which there were none extant and Howe's force had neither a pontoon bridge at hand nor the time or inclination to build one - or a ford, of which there were a shitload. Here they are as they looked on the evening of 10 SEP:

From south to north, the six that lay on the main stem were Pyle's, Chad's, Brinton's, Jones', Wistar's, Buffington's.

Above Buffington's the creek forked. Trimble's Ford crossed the west branch, Jefferis' Ford the east.

The thing about this ground is that there's a "strong" side and a "weak" one.

To the south - Pyle's Ford and downstream - the Brandywine flows into what can be legitimately called a "gorge"; steep walls, deep, fast creek, nasty brushy woods...bad country for formed troops. By the time the Crown troops either hacked through a lower ford or marched far enough to go around this tangle the rebels would have time to head them off.

To the north - above Brinton's or Jones' - the country was much, much different. Hilly, yes, but much gentler, more open. Lots of farms, so lots of farm roads. The Brandywine itself was closer to it's headwaters, so shallower and narrower, the banks less incised.

In other words, Washington had a strong left flank, but the right? Was kind of in the air...a lot like it had been on Long Island. The thing that Washington needed to know was; did Howe know that?

Intelligence and Reconnaissance: Who knew what when?

There are two "stories" to tell about this engagement. One is just bloodyhanded fighting, and we'll get to that in a bit.

But the other is about intelligence (in the military sense) and reconnaissance.

As the modern U.S. platoon leader above is advised; there's no way to be strong everywhere. A smart commander wants to know as much as possible; about their own force, about the enemy's, about the local conditions and especially about the ground, so they can pick where they need to be strongest and where they can go light.

Between 9 and 11 SEP both commanders gathered what information they could about all those factors. How well they did went a long way to determining how the fight would play out.

Howe's intelligence - It's good to have Friends:

The doctrinal position of the politically influential Religious Society of Friends - the Quakers - in Pennsylvania was that a "friend" in good standing would have nothing to do with war and the men who made it.

The political position of many of the southeastern Pennsylvania friends was "fuck these rebels, gimme some King!" So GEN Howe had a valuable source of local intelligence about everything from road conditions to the whereabouts of his opponent.

Supposedly one Chester County Quaker - a joker named Parks - helped the British CG with details about the crossings of the Brandywine. Other locals listed as guides or intel sources are "...John Jackson, a clockmaker from East MArlborough, and Curtis Lewis, a blacksmith and large landowner...both of whom had scouted the fords of the Brandywine the night before." (McGuire, 2006)

Another loyalist - a Philadelphia lawyer named Joseph Galloway - is also credited with providing intelligence, although what level of detail an urban attorney would have had about a minor watercourse in the deeps of rural Chester County I can't imagine. From what I gather Galloway was effectively Howe's Philadelphia spymaster, and so his role might have been procured the people mentioned above

Whoever and whatever the sources, though, by the morning of 11 SEP GEN Howe had a pretty damn good picture of where the Americans were and where they weren't and how to get at them.

Washington's intelligence - Under the lights but still in the dark:

On the other side of the creek GEN Washington was struggling to get good local information.

The damn king-loving Quakers were no help, but Washington and his staff must have been trying to scrounge up as much intel as possible, and the Independence Hall website gives a curiously specific account of how this is supposed to have happened:

"In a War Council meeting held on the 9th of September, several of Washington's generals voiced concern that Howe would try a flanking movement similar to the one he used successfully in the Battle of Long Island in 1776.

Washington called in several Brandywine Valley farmers and probed them. They assured him that the Brandywine was basically impassable above Buffington's Ford on the north." (emphasis mine). "One farmer did tell the Council of a Trimble's Ford, located several miles north of Buffington's, but to get to that ford, the British would have to take a "long circuit through a very Bad Road.

The farmers' testimony convinced Washington that he could protect his position by placing his troops for about five miles along the Creek, stretching from Pyle's Ford in the south to Buffington's Ford to the northwest. By covering the fordable points, Washington expected to thwart any British advance."

I have a shit-ton of questions about this.

For one, the Continental Army was moving most of 9 SEP. It's not impossible that this S-2 briefing might have happened when Washington's headquarters arrived at Chad's Ford, but that seems like an improbably short time to 1) ride from Newport to Chad's, 2) round up a bunch of local farmers (who would be spread out all over hell's half acre because, farming...), and 3) and get through a series of interviews about the conditions along the creek and all the fords.

For another, I can't find anything anywhere like this detailed account - or any account at all - of this "War Council" in any other secondary source, or in any of the primary sources I can track down.

Instead McGuire (2006) provides a source that flatly contradicts the whole "War Council" tale, citing COL Pickering (Washington's adjutant general) as complaining that in occupying the defensive position the Continental staff made the following errors; "...we had time to have viewed all the ground several miles to our right, but did not do it...(did not have) correct maps of the country...(or) guides perfectly acquainted with every road."

This doesn't sound like someone who'd been at a council where the command and staff were fully briefed about the local fords.

|

| I can't find a picture of Chad's before the Route 1 (the old post road) bridge. This is a 1925 aerial, gives you the idea of what the countryside probably looked like in 1777 |

My guess?

Washington and his Division commanders did what they could to try and figure out what was going on to the north. Based on whatever information they were able to gather, the commander and staff made a decision to post formed troops at the four "lower" fords above the main line of resistance at Chad's - Brinton's, Jones' , Wistar's, and Buffington's.

The upper fords - Trimble's and Jefferis' among them - were five miles or more to the north. Too far for a soldier on foot to run all the way back to Chad's to report an enemy movement.

Washington had an app for that, though; COL Bland's Continental Light Dragoons. That should have been the American cavalry's primary mission; securing the northern fords, providing security for the right flank, and performing reconnaissance to the right and front to provide intel on the Crown activities.

None of that happened, and my guess is that three things played into that;

1) Washington laid out his ops order when the army came off the line of march behind the Brandywine specifying the responsibilities for covering all the ford's below Buffington's.

2) He didn't specify anything north of that, vaguely waving his arm at the open country beyond the creek to the north and west. That's what cavalry is for, right? Patrolling out beyond the front and flanks to keep an eye open for armed and irascible strangers?

3) COL Bland, who doesn't seem like the sharpest saber on the saddle, was fixed looking at the pile of enemies around Kennett and proceeded to forget about the north, sending his people out to the west and northwest, where we'll hear from them again, but that's another story...

So here's what I think was going on in the immediate pre-dawn and early morning hours of 11 SEP 1777:

The rebel army had all the fords covered up to the forks of the Brandywine, while out to the west were a sort of random assortment of scouts, horsemen, armed locals, and other troublemakers.

Maxwell's main Light Regiment force had prepared a series of engagement areas along the post road between Kennett and Chad's, while to the north the countryside was dotted with groups of armed Americans ranging from individuals and squads to company-sized elements of militia as well as random Continental light dragoon patrols.

Maxwell's guys were well-organized. But north of the post road there was nobody in charge.

There was no overall coordination, command or control of these recon and security parties, if that's appropriate to call them. Each of the small-unit leaders reported to someone, but that someone wasn't the same someone. So as we'll see, the contact reports they sent filtered in all jumbled up and confusing.

The Intel Brief: Do you know what you don't know? -

So the tl:dr version of the above is kind of simple-but-ugly:

1) GEN Howe's tactical plan called for a fixing force and a maneuver force turning the American right, and what a modern U.S. Army officer would call his "intelligence preparation of the battlefield" or IPB provided him local sources that laid out an axis of advance to give him an excellent chance of executing that turning maneuver and the intel that his opponent seemed ignorant that said axis existed.

2) GEN Washington - like any defender - couldn't be sure whether his enemy would try and smash through his MLR, or sidestep him, or even wait him out while preparing some other sort of trick, like a second landing behind Brandywine along the Delaware River. So he needed to have as much information about the local conditions and enemy actions as he could get...and he didn't get it.

Either through active misinformation or simply lack of information about the northern fords those were unguarded and, worse, the American command didn't know that was an important omission. Through some mix of the same breakdowns the American higher didn't get good tactical intel on the Crown force locations and movements.

The American army still had a lot to learn about war.

Well, GEN Howe was going to teach them.

0500-0645: First Blood

First call in the Crown bivouac must have been sometime in the deep pre-dawn, since the march order was for 0500, 5:00am. So sometime in the darkness between midnight and probably about 0300 or so the officers and sergeants of the night guard began booting guys out of their bedrolls and from under cannons and wagon beds.

The troopers went through all the usual pre-battle routines; stuffed their blankets (underwear, naughty parchments, and all their other ash-and-trash) back in their knapsacks and haversacks, drew their combat rations - probably just biscuit - and filled canteens, checked the sixty rounds in their cartridge boxes, swapped out flints for newly-knapped and sharp ones.

The sergeants made their precombat checks and fell the privates in, checking the company troublemakers and sniffing faces to see who'd been sneaking a gill from the rum barrel.

At 0500 the drums began to beat and the first advance party troops stepped off; light dragoons, riflemen, and rangers northeast down the post road for Knyphausen's Right Wing, jagers and light infantrymen up Unionville Road to the north for Cornwallis' Left.

The gunfire started with a Continental ambush party near "Welch's Tavern" along the post road - the furthest west blue dot above - just after daybreak, and from there a running fight - four separate small engagements - between the Right Wing advon and Maxwell's Lights.

They're all very dramatic and exciting, especially for the Loyalist units - they got pretty badly shot up that day, including MAJ Ferguson who took a bullet in the arm that shattered his elbow - and the American Lights who were left along the post road. Any day you die is a bad day, and you can have a bad day in some shitty meaningless roadside shootout just as much as in the Valley of Decision.

If you want the full details the CCPC site has them; worth a read for the thud and blunder...

(One interesting little note is that some the Crown lead elements - specifically the Rifles - had figured out the whole "find cover" idea; when the American lights would volley Ferguson's guys would go to the prone and let the bullets go overhead. We'll see this again at Birmingham Hill, but in general this was not cool in 18th Century infantry drill, so the Continental Lights saw Tories go down and just figured they'd killed a whole bunch of bad guys, and the enemy KIA numbers reported in Washington's account are ridiculous. But that's war for you...)

...but all very much black-powder-battle-business-as-usual.

No, the thing that interests me is what was happening north of Kennett.

|

| Trimble's Ford |

Cornwallis' Movements and the Recon Failure - 0500-0645

As you can see from the map above, the Crown Left Wing marched out of Kennett directly north along what is today Unionville Road, across Street Road (the thin straight line about 2/3rds the way to where the red column makes a right turn, and turned east along what is today's Doe Run Road.

The day was warm and sultry, and a combination of woodfire smoke and fog made visibility poor. But within a short distance the Crown forward element - Hessian jagers led by our old pal CPT Ewald - ran into American recon parties.

"I hardly marched half an hour when I met with a warning post of the enemy, five to six hundred men strong, who withdrew from one favorable position to another under constant skirmishing until around noontime." Ewald wrote.

So.

Someone - one of the Light Regiment scouting parties, a Chester County Militia outfit, possibly some of the Continental Light Dragoons, or some combination of all three - saw Cornwallis' wing on the road north early in the morning.

Why the fuck didn't the officer in charge of this American outfit send a galloper going balls-out to Washington's headquarters to report this?

I mean...if ever there was an "essential element of information" it was this. Washington's tactical plan was predicated on a frontal assault across Chad's Ford. If there were Crown forces moving north, the only reason for such a move was to try and turn the American right. Didn't matter where; Jones' Ford, Buffington's, an enemy column not moving directly east was a potential threat to Washington's right, and a well-briefed recon team leader should have known that and had his hair on fire as soon as he heard the first tootle of a fife.

But as we've discussed; these "recon teams" weren't well-briefed and they weren't well led. The whole grab-ass "recon" operation was twelve monkeys fucking a football, and this was no exception.

Operations, 0645-0930: The intelligence plot thickens -

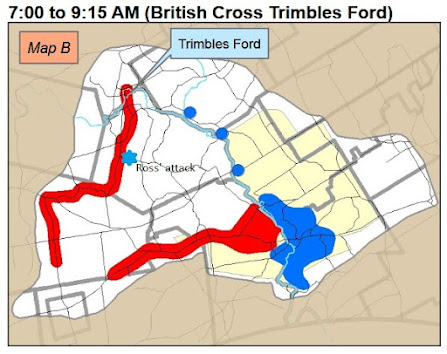

By about 9 or 10 am the Crown Right Wing had reached Chad's Ford, and the Left Wing had made it's first crossing point at Trimble's Ford along the West Branch.

At Chad's GEN Knyphausen was following his instructions, making noise - mostly with his small artillery battery - but holding in place.

GEN Cornwallis' element was moving steadily, lightly harassed by American recon elements, but without significant delay. The real question is, as discussed, why this movement hadn't drawn the attention of the American command and staff.

|

| Anvil Tavern along the post road. Maxwell's lights and the Tory units had a firefight here. |

Certainly there had been some disturbing reports. To try and simplify what is a very confusing chronology I'm going to try and summarize what I think that Washington knew up until about 1300:

American Intelligence, 0645-1200

0700: The Independence Hall site claims that the initial report of the Crown Left Wing's northward movement reached Washington early in the morning. I'm not sure about this; I can't find a specific mention of such an early report in any of the primary sources, although it might have been what MG Sullivan was referring to when he wrote later: "It was ever my opinion that would come round on our right flank...I sent him two messages...& the first intelligence I received, that they were actually coming that way." This could have been that the first American recon team actually did what they were supposed to, tho why this wasn't considered definitive, well...we'll see.

0900-0930(?): MG Sullivan - who as we've seen was nervous in the service about these damn redcoats sneaking around the right side - passed on a message from COL Hazen of the 2nd Canadian Regiment saying some of his guys had seen British troops moving north past Wistar's Ford.

0900-0930(?): According to the Mt. Vernon site one COL John Jamison of the 3rd Continental Light Dragoons reported to MG Sullivan who passed on this version of Jamison's report: "...he came from the Right of the Army & I might Depend there was no enemy there". The Mt. Vernon site account continues Sullivan writing: "...another officer sent in the same direction returned to say that "no Enemy had passd that way."

0930-1100(?): Another American recon officer, a MAJ Spear of the Chester County Militia, reported no Crown movement to Washington's right. The timing of the delivery is difficult to be sure; the message preserved after the battle has no time stamp (and note that this might be the "other officer" mentioned by the Mt. Vernon site).

Sullivan's message, supposed received at Army HQ about 0930 stated: "This morning from a Tavern Called Martins on the Forks of Brandywine he (Spear) Came from thence to Welches Tavern & heard nothing of the Enemy about the Forks of the Brandywine & is Confident they are not in that Quarter."

1115-1130: GEN Washington, peeved at all this clusterfuck, sent a nastygram to COL Bland:

Chad's ford 11th Septr 1777

20 mints after (??) O'clock

Sir:

I earnestly entreat continuance of your vigilant attention to the movements of the Enemy and the earliest report, not only of their movements, but of their number & the course they are pursuing. In a particular manner, I wish you to gain satisfactory information of a body confidently reported to have gone up to a Ford Seven or Eight miles above this. I is said the fact is certain. You will send up an intelligent - sensible Officer immediately with a party to find out the truth - what number It consists of and the Road they are on, be particular in these matters. I am Sir your Hble Servant."

1200: COL James Ross - of "Dunlop's Partizan Regiment" - message is delivered to GEN Washington:

Sept. 11 '77 Great Valley Road

Eleven O'clock

Dear General.

A large body of the enemy - from every account 5000, with 16 or 18 field pieces, marched along this Road just now. This Road leads to Taylor's & Jeffries ferries on the Brandy wine.

Here's an interesting bit of historical disagreement, though.

McGuire (2006) is pretty definitive that the Ross unit engaged Cornwallis' Left Wing near Trimble's Ford. That would put the timing of the encounter near 0900, and make the message a couple of hours late.

The CCPC (2020) account disagrees; it puts the encounter further south, near what is today the intersection of Red Lion Road and Corinne Road. That would make the time somewhat earlier, around 0800, and the message very late.

So there's two issues here: the location, and the timing.

Normally I'd suspect that a sharp officer would have fired off the message ASAP, making a case for the encounter being near Trimble's.

On the other hand. in 1777 Red Lion Road was part of the main route to the "Great Valley", whereas the road from Trimble's to Jefferis Fords was a local road. You'd also think if Ross WAS between Trimble's and Jefferis he'd have mentioned that. And nobody else in the American recon element seemed like they were in a hurry,so I'm not sure that the time gap is critical.

Based on the above I tend to agree with the 2020 work, and I've added the blue star to the map above to show where the CCPC (2020) and I think the encounter took place.

You'd think that Ross's message would have settled any uncertainty about whether the British were coming. But McGuire (2006) says that the Sullivan report of Spear's all-clear is delivered just afterwards, muddying the waters (The Independence Hall site places the Spear message as arriving even later, at about 1300).You get the idea. The American higher had no surety what the Crown left wing was doing.

Now.

You'd think this was pretty crucial, and you'd think that GEN Washington would have a) made that clear to all his subordinate commanders, and especially pointed to his recon-and-security guys, and b) a cavalry officer like COL Bland would have made it his business to have had eyes and ears out, particularly to the spookily-wide-open American right.

Well.

That didn't happen.

What happened instead was, frankly, kind of weird.

Operations, 0930-1200: The Americans move

MG Greene's Division and the Light Infantry would cross the ford at Chad's to fix the Crown center, while Sullivan's Division would bull across at Brinton's and hit Knyphausen's left. Both sides geared up for this encounter. Sullivan pushed part of the Maryland Brigade against the Queen Rangers across Brinton's, while Greene's troops and the Lights exchanged fire with the Rifle Corps and the 4th and 5th of Foot. Both sides' artillery hammered at the infantry lines.

This is the point where McGuire (2006) says the Spear message arrived; if so, says McGuire, it made Washington hesitate. Maybe all this supposed flank marching was a trick; maybe Cornwallis was lurking somewhere back out of sight, waiting for a portion of the American infantry to cross the creek so they could fall on it and do the defeating in detail.

Washington wouldn't risk that.

A Napoleon might have, but a Napoleon would have had a couple of corps of the Grande Armee capable of executing the sort of smashing attack that would have shattered Knyphausen's force before Cornwallis could effect the fight.

Washington didn't have that; as we'll see, he had an army that had trouble organizing itself for a simple linear defensive fight.

So instead he called Sullivan's troops and the Lights back, and kept Greene's Division from crossing, and the lower Brandywine settled back into an uneasy standoff.

Operations 1200-1300: The Crown Left Wing takes Osbourne Hill