"It is the hardest thing in the world to frighten a mongoose, because he is eaten up from nose to tail with curiosity. The motto of all the mongoose family is "Run and find out''; and Rikki-tikki was a true mongoose."

~ Rudyard Kipling, "Rikki-tikki-tavi"

We've come to Part Four of our look at the opening campaign of what would become known as the "Western Front" of World War One; the so-called "Battle of the Frontiers" that officially includes everything from the first shots fired on 1 AUG 1914 to the first day of the First Battle of the Marne, 5 SEP.

Part One - the geopolitical and diplomatic run-up to war - is here, Part Two (German war planning) is here, and Part Three (French war planning) is here.

Remember that the hypothesis of our study is that among the, or possibly the - most critical elements of how the battles in August turned out was that either:

1) The two sides' plans - from tactical to operational and possibly even to the level of strategy - made some assumptions about their ability to gather intelligence once the shooting started that were wrong, and which meant that those plans miscarried because they were formed on incorrect assumptions.

Or?

2) That the tactical conditions had changed, far beyond the ability of even the cleverest plans to account for them. Was the problem that the older means and methods of reconnaissance - horse cavalry and light infantry - and security were just no longer effective in the tactical environment of 1914, and the new techniques - air reconnaissance - un- or under-developed to the point where the commanders didn't receive (or were unable to process) the intelligence.

But to talk about this sensibly we need to first explore those people (and their organizations, equipment, and training) whose job it was to "run and find out", the eyes of the armies; the reconnaissance (and counter-reconnaissance) units.

We're going to take them in order of seniority; first the infantry, then the cavalry, then the fliers also in order of lighter-than-air (airships and zeppelins) to heavier-than-air craft.

Because of the size of this topic we're going to split them out even further.

This post we'll look on the ground, at infantry and cavalry scouts. The next post - 4b - will cover things that fly.

With that, let's begin with the

Infantry

The first group - the "light" infantry scouts - we can dispense with briefly, because by 1914 their days as a collector of intelligence and reconnaissance beyond their immediate vicinity had long since gone.

There had been "light infantry" units going back to Alexander's peltasts and Scipio's velites.

But gunpowder, and more specifically the inaccuracy of the smoothbore musket that took over from edged weapons in the late 1400s, meant packing the joes into dense masses so they could actually hit anything.

For about the next two hundred years or so infantrymen fought mostly as close-ordered groups. The relative handful of specialized "light" units were guys like these guys...

...chasseurs alpins, trained to fight only in specialized terrain like mountains or forests.

Then, at the end of the 18th Century:

1) The British Army encountered the topographic and tactical conditions of North America, and

2) The French Army was torn apart by revolution and reassembled in a scrambling fashion.

Both experiences resulted in the creation of large, organized units of light infantrymen; the British Army largely through the efforts of Sir John Moore at his Shorncliffe training camp in the early 1800s, the French Army as a result of the mob of "sans-culottes" whose random lack of old school linear discipline fastened onto the light infantry experiments that the royal army had begun in the mid-18th Century to create swarms of light infantry.

It was these French lights - chasseurs (literally "hunters"), voltigeurs, and tirailleurs - who made the strongest impression on other European armies.

The French revolutionary infantry tactics and the imperial light infantry that evolved from them were characterized by a mass of light troops preceding the heavy infantry blocks. These included the full battalion-sized units of infantrie legere as well as the light companies (usually called voltageurs instead of chasseurs) of the line units.

These guys fought alone, in pairs, or in small groups, using what cover and concealment they could to harass and disrupt (meaning wound and kill people in) enemy infantry formations, breaking cohesion and morale to open opportunities for the French line battalions coming up behind them.

By 1815 all the European armies had some version of this; British Light and Rifle battalions, Prussian jägers and schutzen, Russian jager, and Austrian Grenz and jäger units.

But.

All these guys were purely short-range and tactical. They couldn't move faster than a fast man could run, and had all the other limitations of infantry; the heavy load of weapons and equipment that had to be carried by each individual, their observation range that of the Mark I eyeball at the tallest man's height.

Through the 19th Century improvement in rifle and artillery range and accuracy meant that soon all infantrymen needed to move as individuals or small groups, not just the lights.

So by 1914, the distinction between "light" and "line" infantrymen had become largely notional, expressed in the blue trousers of the chasseurs in place of the line dogs' red...

...or the leather caps of the jäger in place of the spiked helmet of the line infantry landser;

Infantry formations still typically sent out a screen of patrols to the front and flanks, but their role in even tactical reconnaissance was pretty minimal.

So on the ground that left the...

Cavalry

About the same 19th Century time as the line and light infantry organizations were formalized in European armies the horsemen were being sorted out, too.

On the one hand were the "heavy" cavalry, the big men on big horses whose job was to ride into - and over - enemy infantry, cavalry, and artillery units. These "shock" cavalry units included the last armored horsemen in Europe, called cuirassiers from their metal armored vest.

All the continental armies had some version of these guys, called kurassier in Germany (and Austria) though only the French - as the photo shows - wore the cuirass into the field in 1914.

Other "heavy" cavalry included for formerly-not-quite-cavalry (we talked about this back in 2017 when we looked at the 1683 Siege of Vienna) called some kind of "dragoon", as well as mounted carabaniers, which by the 19th Century were practically indistinguishable from cuirassiers.

Other names for heavy cavalry were "Garde du Corps" (that is, "bodyguard" or household cavalry - the British did, in fact, have a "Life Guard" heavy cavalry) and "Schwere-Reiter" literally "Heavy Rider" but effectively "Heavy Cavalry".

At least in theory these guys were supposed to charge, sword in hand, in 1914 just as they had in 1814.

The other hand were the "light" cavalry. These guys were the original cavalry scouts, whose job was out front of the army in advance, to find the enemy force (and to fight off the enemy light cavalry who were trying to do the same thing), to the flanks to detect the approach of enemies from that vulnerable direction, as well as behind the army in retreat to screen and delay pursuit.

This light horseman was probably most dashingly embodied in the hussar units:

These are French but every continental army had them. The British Army for some odd reason, refused to get into the hussar business until well into the Napoleonic Wars, preferring to call their light horsemen "light dragoons".

The German Army of 1914 also had something called a Jäger zu Pferde, technically by the meaning of the term a mounted light infantryman but supposedly pure light cavalry by August of that year.

The French Army also had "Chasseurs a Cheval", who were just what the name implies, as well as "Chevau-Légers" - "light horse" - and "Chevau-Légers Lanciers", light lance-armed horsemen.

The German and Austrian armies had their own versions of this lancer, called a uhlan (or ulan in Austria). And that's part of an interesting story about the opening of World War One.

Because for some reason - I can't find any explanation for it - the German Army issued all their horsemen a lance in 1889.

I'm not sure if the kurassier and dragoon units retained their swords; officers and some NCOs surely did, and enlisted troopers in all units were issued a carbine version of the standard infantry Gewehr 98 rifle, the Karabiner Model 1898 AZ.

But the result is that for British and French soldiers ALL German horsemen were "uhlans".

We'll go into this in detail in a bit, but by 1914 the distinction between "heavy" and "light" cavalry had eroded.

The cuirassiers and dragoons were expected to scout along with the hussars and lancers. And both were expected to charge home when the opportunity presented itself.

The two types sprang from very different histories and maintained very different traditions, though, and it's my suspicion that that affected their performance in 1914; we're going to talk about that further down the page.

The general idea, though, seems to be that the cavalry units would use their horses for grand tactical (at least!) mobility, ranging out in front of the infantry columns. When they made contact, well...I think the idea was to try and scout from horseback like these guys...

...but the reality of modern rifles kicked in quickly. To stay alive the cavalrymen would have to dismount and sneak forward on foot, leaving the noble steeds (hopefully) in some safe defilade somewhere.

Remember, the portable radio was decades away. Once the recon troopers had counted enemy heads and scribbled down equipment numbers and type the report would have to be galloped back to the nearest telephone relay or big radio transmitter being carted around by the corps-or-higher headquarters element, and we'll go into where these were in a bit.

And, don't forget, the idea was that the forward cavalry patrols would also fight off enemy cavalry which was trying to find their opposing infantry main force units.

It was a big ask, and we should talk about who it was being asked of.

Cavalry Organization

Let's look at the mounted arm of the four militaries that met in the frontiers of France, Germany, and Belgium in August, starting with the smallest:

Belgium

The small Belgian Army - about 200,000 all arms - had a total of ten, or eleven, "regiments" of cavalry.

I use the scare quotes because I'm having trouble finding a source that breaks down the regimental organization further, so I'm not sure exactly how these units would have been deployed.

For example, a typical German cavalry regiment - let's pick one, say the Königlich Bayerisches Ulanen-Regiment "Kaiser Wilhelm II., König von Preußen“ Nr. 1 a Bavarian Uhlan unit with an authorized strength of about 700 troops (all ranks) in August 1914 meaning that a German cavalry "regiment"...

...was the equivalent of an infantry battalion, rather than an infantry "regiment" which could, and often did, have two or more battalions.

This regiment would have been broken down into squadrons - the cavalry equivalent of an infantry company - of about 150 to 175; the uhlans had four of these eskadronen, but a regiment could have up to six,

(The cocky youngster to the left is one Franz von Grafenstein of the above-named outfit, looking like nothing but trouble.)

The squadron, in turn, broke down into four platoons (Zug in German) that had an even smaller sort of "squad" subunits divided by rank and file.

But the sources I DO have don't break the Belgians down, so I have to guess that their cavalry "regiments" were similar battalion-size units, between 500 to 700 strong with internal squadrons and platoons.

Given the reported condition of the Belgian Army I suspect that the Belgian horsemen were, at best, equipped with a rifle - the Belgian Army history site says that "The Guides and Lancers Regiments were armed with a short version of the Mauser 1889, a sabre and a lance." - but lacked anything heavier; no machineguns or attached artillery.

It's worth noting that the Belgians, at least, had quit kidding themselves about the whole "heavy" cavalry nonsense.

There were no Belgian cuirassiers. All Belgian cavalry were "light"; lancers, chasseurs, or "guides" (these were the "household cavalry" of the Belgian royals).

The one thing the Belgians did that the major combatants also did was divide their cavalry into "tactical" and "strategic" elements.

The "tactical" cavalry units were the individual regiments assigned to the infantry divisions. There were six, one per division, whose mission was scouting and screening for the infantry and artillery of their division. Here's an organizational chart for the first four divisions:

So the First Division commander depended on the 3rd Lancers to be his eyes and ears, as well as keeping the enemy cavalry off his guys' asses.Note that I've added the "(Infantry)" tag to the first two divisions because that's what they were. But the Belgians didn't actually work that way; these were just "divisions" - "First Division", "Second Division", and so on.

But.

There was a seventh division, only it wasn't a "division" like the other six.

It was the "strategic" cavalry outfit, the "Cavalry Division":

Note the other four cavalry regiments were assigned to the Cavalry Division, as well as a "mounted" version of the artillery regiment that all the other divisions had in "foot" form (meaning that the horse artillery gunners rode while the regular redlegs walked; the guns and the ammo limbers for both had horse teams for prime movers).

The idea was that the "Cavalry Division" would screen and scout for the whole Army while the divisional cavalry would do the same for their divisions, like this:

That was the idea, anyway, but when the Belgian Army mobilized in August 1914 it looked like this:

See the problem?

The supposed "strategic" recon and security guys are way the hell west and north of where they should be:

What can I say? That there's a reason there are few Belgians in the "Great Captains of History" stories?

You get the idea, though. The pre-August-1914 thinking was that the horse soldiers would do what they'd always done; find the enemy, figure out what they were up to, report back, while fighting off the enemy cavalry that were trying to do the same things.

So. Let's look at the cavalry forces of the three real players in this game, starting with...

Germany

We looked at the German cavalry regiment just above. But where did those cavalry regiments go?

Divisional Cavalry?

Yep. The lowest level of "tactical" cavalry showed up in the infantry divisions, which each had a cavalry regiment:

So, for example, the 8th Infantry Division (part of IV.Armeekorps in First Army) included: 15.Infanterie-Brigade:

Füsilier-Regiment General-Feldmarschall Graf Blumenthal (1. Magdeburgisches) Nr. 36

Anhaltisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 93

Magdeburgisches Jäger-Bataillon Nr. 4

16.Infanterie-Brigade:

4. Thüringisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 72

8. Thüringisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 153

"1/2" Magdeburgisches Husaren-Regiment Nr. 10

8. Feldartillerie-Brigade:

Torgauer Feldartillerie-Regiment Nr. 74

Mansfelder Feldartillerie-Regiment Nr. 75

2./Magdeburgisches Pionier-Bataillon Nr. 4

3./Magdeburgisches Pionier-Bataillon Nr. 4

The hussars were the last remnant of what had been a full brigade of cavalry; here's the the 8th ID MTO&E in 1913:

15.Infanterie-Brigade:

Füsilier-Regiment General-Feldmarschall Graf Blumenthal (1. Magdeburgisches) Nr. 36

Anhaltisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 93

16.Infanterie-Brigade:

4. Thüringisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 72

8. Thüringisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 153

8. Kavallerie-Brigade

Kürassier-Regiment von Seydlitz (Magdeburgisches) Nr. 7

Thüringisches Husaren-Regiment Nr. 12

8. Feldartillerie-Brigade

Torgauer Feldartillerie-Regiment Nr. 74

Mansfelder Feldartillerie-Regiment Nr. 75

Landwehr-Inspektion Haale an der Saale

As the division's Wiki entry notes: "On mobilization in August 1914...most divisional cavalry, including brigade headquarters, was withdrawn to form cavalry divisions or split up among divisions as reconnaissance units", so the Madgeburg Hussars were all that remained of the 8th ID's tactical recon and security element.

(As the photo above shows, the German hussars were the only Imperial cavalry to wear something other than some sort of helmet. The fuzzy hat - called a "busby" in English and typically a "kolpak" in German - was the traditional headgear of the original Hungarian hussars and spread from there across Europe.)

Army Corps Cavalry?

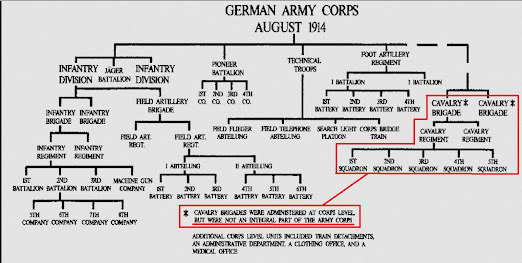

Interestingly enough, a German Armeekorps had no organic cavalry:

As the above diagram shows, the TO&E included cavalry brigades attached to the corps-level units, but that in practice the cavalry was either not present or, at best, what the US Army would describe as "opcon", giving the corps tactical direction of the cavalry unit(s) but not logistical or organizational support.

So tactical cavalry at the division level - a bit, one regiment per division - but normally nothing at corps.

How about...

Armee (Field Army) Cavalry?

Well...this is where things get interesting.

The Imperial Army in the West did have cavalry units at the Army level...sort of.

Imperial HQ - as described in the division comments above - broke up the cavalry brigades assigned to the divisions. A handful stayed. But what about these "cavalry divisions", and why weren't they assigned to a corps?

Because...they were grouped, instead, into their own corps; the HKK.

Note: There seems to be some disagreement about what this acronym stands for. The English translation is usually given as "Higher Cavalry Command", but I've seen it spelled in German as "Heereskavalleriekorps" - which doesn't mean the same thing. "Heeres" means "armies", so "Army - or, more correctly, Armies - Cavalry Corps"...except in German a "corps" is usually termed a "armeekorps". or "Höherer Kavallerie-Kommando" which gives the correct German for "higher" but which swaps out "corps" for "kommando" which can mean "unit" (as in a military unit) or "command" (as in "high command"; the German term for the overall military HQ in the Second World War was "Oberkommando der Wehrmacht", abbreviated "OKW".

The latter matches the English translation better, so makes more sense to me in terms of what the Imperial Army meant by these things.

Here's an organizational chart for the entire Imperial Army in the West. The HKK cavalry corps are outlined in red:

Each HKK contained two (or three for HKK 2 and HKK 3) cavalry divisions, which were full divisions; 12 cavalry regiments (HKK 1 had 14 because it included the 8-regiment Guard Cavalry) and "divisional troops" like horse artillery, engineers ('pioniere" in German), signal - including radio commo - and machinegun units.

Curiously the HKK itself had no "corps troops" directly under the flagpole; no corps artillery or engineer or signals units as was typical of the Imperial armeekorps (or the British corps and French corps d'armee).

What the HKK did have - for wartime, anyway - were attached light infantry units.

We've discussed these jäger infantry just above, but the cavalry jägers included bicycle and truck-transport mobility to keep up with the horses. HKK 2 had five battalions of light infantry, HKK 1 had three, the other two had two battalions each.

These light infantrymen added a serious punch to the German strategic cavalry corps.

These HKK cavalry corps were parceled out to several of the Imperial field armies, but not in the way you'd think given the 1914 operational plan.

Given the way the "big right hook" demanded a rapid swing through Belgium and envelopment of the French (and British, presumably) left that the logical way to divvy up the HKKs would look like this:

The right wing armies SHOULD have had the vast bulk of the "strategic" cavalry. The "big" reconnaissance work was out there on the German right, with First and, to a lesser degree, Second Armies. Give them operational control of the strongest cavalry corps, HKK 1 and HKK 2, and maybe even HKK 3.

Third Army might have call on HKK 3 - Third was part of the "hinge", after all - but the other left-center and left flank armies could all share one; their reconnaissance needs would be primarily tactical anyway.

Instead, here's how the Imperial General Staff allocated the cavalry corps:

You can see the problem.We'll talk a lot about this in the parts of this series yet to come.

So German Cavalry all tolled?

"Strategic reconnaissance" cavalry: 60 regiments in 10 cavalry divisions in 4 cavalry corps (with 12 attached jäger battalions) opconned to the field army commands..but not in a particularly sensible way.

"Tactical reconnaissance " cavalry: 44 regiments (including several split into 3-squadron half-regiments) in 50 infantry divisions.

The other "big" player along the frontiers was, of course,

FranceThe French cavalry included the traditional "heavy" cavalry; cuirassiers and dragoons - indeed, the French cuirassiers were the last horsemen in Europe to go to war wearing their antique armored breastplate (albeit covered with a cloth cover to dull the fatal shine) - and the "lights"; chasseurs and hussars.

French horsemen were armed and equipped similar to their European counterparts; typically a long straight-bladed sword and a rifle, in this case the Carabine de Cavalerie Modèle 1890, a five-round clip-loaded weapon similar to the German Kar98AZ.

Peculiarly, French dragoons carried a lance to war in 1914 despite having no tradition of such prior to the period. I'm not sure why, perhaps it was in response to the sort of goofy army order that issued every German horse soldier a pig-sticker in 1889.

Go figure.

Similar to the Belgian and German armies, the French cavalry was based on a "regiment" that was effectively battalion-size (about 500-800 all ranks) composed of four to five company-sized "squadrons" which had further platoon-sized internal subdivisions.

However, the French Army seems to have had a very different idea of dividing up their mounted troops. Unlike the Germans, where cavalry bypassed the armeekorps and jumped from division straight to field army, French maneuver units at almost every level above the infantry brigade had their own assigned organic cavalry element:

At least in theory, the French Army of 1914 was better set up for tactical reconnaissance above division level.

At corps the German armeekorps of two infantry divisions could throw one to two cavalry regiments - call it 1500 troopers or so - out in front, while a French corps d'armee could field between 2 regiments - assuming two divisions - up to 4 regiments, something like 2,000-2,500 horsemen.

Above corps, though, the Germans were better fixed for strategic reconnaissance assuming that the Imperial field army had a HKK out front - that added between 12 and 14 cavalry regiments plus light infantry and all the cavalry divisional troops like field horse artillery and radio commo guys.

The French had a single Cavalry Corps for the entire Western Front; 18 regiments in three divisions.

The actual performance of all these horsemen, though...well, we'll get there.

First, let's look at the last of the "big" combatants (though they were "big" only in relation to the Belgians),

Great Britain

The "British Expeditionary Force" wasn't quite an ad-hoc outfit thrown together for the outbreak of continental European war...but it was close.

The original British mobilization plan called for the infantry divisions - six, of three brigades each of four battalion-sized infantry regiments for a total of 72 battalions - and the single 12-regiment cavalry division to be run directly by the CG BEF.

That was hastily ruled impractical, and a corps structure was improvised for the infantry.

The result was a "corps" lacking reconnaissance assets, more similar to a German armeekorps than its French ally.

Each infantry division had a single squadron of light cavalry, corps had nothing, and the field army had a total of 15 cavalry regiments; 12 in the cavalry division and three in an independent brigade.

British cavalrymen came in similar flavors to the French and German varieties, with one significant exception: no cuirassiers/kurassier

Well, the British did sorta-kinda have this type of formerly-armored horsemen, in the form of the two "Household Cavalry" regiments, the Life Guard and Royal Horse Guard.

You've seen them, riding around London or pulling guard outside Buckingham Palace dressed up all pretty and shiny with the nose-poking helmets.The ones in red are the "Life Guards" and they're the ranking unit in the Royal Army, the folks who preceded everyone...

(except the Royal Horse Artillery when they parade with their cannon, he's reminded by the Military Pedant)

...and are followed directly by the similarly-outfitted-only-with-a-blue-jacket. These used to be the Horse Guards, known for their coats as "The Blues"...

(the Horse Guard was merged with a line cavalry regiment in 1969 to become the "Blues and Royals" today)

...whose attitude was probably just as snotty as the Life Guard towards the other not-guard-units.

But the numbers were tiny compared to the rest of the cavalry, so the whole "armored heavy cavalry" thing (as we'll discuss in just a bit) was much less of a thing in the BEF compared to France and Germany.

The other British cavalry included dragoons on the "heavy" side, and lancers and hussars as "lights".

This is probably a good time to break in and discuss these cavalry "weights" and what they might have meant in 1914

Heavies versus Lights - 1914

As we discussed earlier, by 1914 the two mounted unit groupings had been forced closer together in battlefield tactics and techniques by magazine-fed bolt-action rifles, machineguns, and quick-firing artillery.

But.

Although I can't find anything specific, my guess is that both unit type/tradition and national experience resulted in some differences in cavalry reconnaissance and screening effectiveness in August.

CuirassiersThe heaviest of the heavy cavalry were the cuirassiers of France, the kurassier of Germany, and the household cavalry of the BEF.

All were the tanks of the mounted arm, and all were probably the closest tactically and mentally to the "sword-in-hand-mounted-charge" standard of the 19th Century.

The war service of 1866 and 1870 hadn't entirely shaken the continental cavalry of the old ways; events like "von Bredow's Death Ride" at Rezonville in 1870 convinced many observers that the old mounted charge was still a workable tactic.

That would have been just nuts to the armor-vested (or, at least, in their imaginations still armored) troopers.

So my guess is that German and French cuirassier units were merely "okay" at scouting and screening. Their thing was riding down enemies, not sneaking around spying on them.

The Germans had 14 regiments of kuirassier or similar heavy cavalry (out of about 100 cavalry regiments overall), the French had 12 out of about 80 regiments all tolled. The British technically had two, but only a single composite regiment of Guards landed in August among the 15 regiments in the BEF.

Dragoons

By 1914 these guys had come a long way.

As we talked about above and in the linked Vienna post, they got their start as sort-of-mounted-infantry, the red-headed stepchild of the cavalry. In 1600 nobody in his right military mind would have sicc'd mounted dragoons on real cavalry; the dragoons would have been considered lucky just to have stayed in the saddle.

By 1700, though, things were changing, and by 1800 most dragoons were pretty much your basic medium-to-heavy-cavalry...but they were still trained to, and could, scout and skirmish on foot.

By 1900, well, most armies had more of them than any other type of mounted troops; the German cavalry included 28 regiments of dragoner, the French 32 dragoon outfits, and the BEF five of their 15 regiments were some sort of dragoon.

In 1914 "dragoon" was kind of the default cavalry setting.

My guess is that these units were fairly effective scouts, and could screen pretty well, too. Perhaps not quite as well as the light cavalrymen, but sort of the "median" recon-and-security outfit for the time.

Chasseurs, "Light Horse", Lancers, Uhlans

These units were the median light cavalry the way the dragoons were the median heavies.

Their "traditional" (i.e. 18th and 19th Century) role was, as we discussed, reconnaissance and counter-reconnaissance, so presumably they trained on it more and were better at it than the heavies.

The French Army had 19 regiments of chasseurs a cheval, the Germans 8 of "chevau-legers". France had no remaining lance cavalry but Germany had a truckload - 24 regiments of uhlans - and the British had four lancer regiments.

Hussars

The quintessential light horseman, scout, and raider. France fielded 13 regiments, Germany 21, and the British five.

There was another factor that would have impacted the cavalry's performance, though; national experience.

France and Germany versus Britain

British cavalry had living memory of fighting an enemy armed with modern 1914-style rifles in the Boers of southern Africa, and not a happy one.

The Wikipedia entry on the British cavalry's experience does a good job of explaining this:

"Their Boer opponents taught not only the cavalry but the whole army some lessons. In one engagement at Dronfield, 150 Boers held off the British cavalry division, which was then supported by several artillery batteries, and at Bergendal 74 men held up the entire British Army. So effective were their tactics that they forced the British cavalry, if only for a short time, to leave their swords and lances behind and concentrate on their firepower. This proved to the British Army the value of a full size rifle over a carbine. Soon the cavalry were practising working dismounted and advancing in open order."

They'd learned the hard way; when your enemy can reliably hit a man-sized target at several hundred meters a horse-sized target is almost unmissable.

This drove the British to several doctrinal changes that the continental cavalry did not adopt, including tactical emphasis on dismounted fire that was made more effective through more range time and the issue of a battle rifle (the British horsemen were the only cavalrymen to carry their infantry's service rifle instead of a specialty carbine).

In fact as noted in Herrmann (1996) one of the continental criticisms of the British

horsemen of the pre-war years was their supposed aversion to coming to

handstrokes. In other words, the British cavalry were entering the 20th Century while the others - Belgium, France, and Germany - still lingered largely in the 19th.

We'll see whether and, if so, how much of a difference this made.

But first...

Next: Those Magnificent Men In Their Flying Machines or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 Hours 11 Minutes...

.jpg)

1 comment:

Very interesting, Chief. I wonder if Belgium's placing of their OMG cavalry was down to facing in three directions? They weren't officially part of the Entente until the invasion - indeed, the existence of their country was contingent on not being part of any alliance ever - so I wonder if they drew up their war plans unsure whether they'd be fighting the Germans, the French or even the British? But as you say, no Belgian leader has so far made the top 100 list.

The cavalry talk dovetails nicely with some research I was doing earlier in the year on a famous incident. In 1932, NSW Premier Jack Lang was about to cut the ribbon on the brand-new Sydney Harbour Bridge when suddenly one of the cavalrymen in attendance rode forward and slashed at the ribbon with his sword. He turned out to be one Francis de Groot, a Great War veteran who'd served with the 15th Hussars before emigrating to Australia post-war. He wasn't part of the official party, but with his old uniform and a borrowed horse he'd blended in with the attending troop of NSW Lancers until the crucial moment.

Interestingly, some witnesses said he failed to cut the ribbon with his sword and it only parted when his horse reared up and broke it with its hooves. That sounded unlikely until I learned the Pattern 1908 cavalry sabre was basically a sharpened crowbar, designed for skewering not slashing.

Anyway, despite being one of this country's most famous incidents, only the most recent retellings seem to mention his political leanings: Rather than some sort of loveable larrikin, he was a member of a fascist paramilitary called the New Guard, there to protest the socialist-adjacent leadership of Lang. Funny, that...

Post a Comment