Forces Engaged: United States Army - Twelve companies of the 7th U.S. Cavalry, approximately 30 officers and 600 enlisted troopers.

Forces Engaged: United States Army - Twelve companies of the 7th U.S. Cavalry, approximately 30 officers and 600 enlisted troopers.The reality of post-Civil War U.S. Army life included a variety of troubles, some irritating, some debilitating. One of the more severe was the problem of recruitment. The Army was not a desirable career for a young man in the late 1800’s, and the Army had great difficulty procuring both troopers and officers. Many men who could deserted, and units fought constantly to keep the desertions down and the proportion of raw recruits from making units combat incapable.

The authorized strength of a regular cavalry regiment on the United States Army had been declining since the end of the war as the U.S. tried to save money on soldiers that could be better spent on no-bid contracts to political cronies, or something. From a high of 1,195 enlisted soldiers authorized in 1866 the numbers declined to 980 in 1868, 930 in 1869, and finally 845 by 1874. The assigned strength of the regiment on 31 DEC 1875 was reported as 797 troopers. But on 25 JUN the official assigned strength of the 7th Cavalry Regiment is cited in several sources as only 45 officers and 718 enlisted soldiers.

And when the unit rode down into the valley of the Little Bighorn River it was 14 officers and about 100 troopers short of its assigned strength. This was through a variety of reasons, including sick calls, desertions, and detachments, including its commander, COL Samuel D. Sturgis . Detachment was common in the understaffed Army of the late 19th Century, and that explains all these captains and majors commanding “battalions”.

About 15-20 percent of the soldiers who rode down off the high bluffs that day were barely trained. They could ride, sort of, and knew which end of the carbine the bullet came out of. But that was pretty much it. And although portions of the 7th were relatively experienced with the sort of fight they were about to meet, roughly half the regiment had been stationed in the former Confederacy for the previous year and a half.

About 15-20 percent of the soldiers who rode down off the high bluffs that day were barely trained. They could ride, sort of, and knew which end of the carbine the bullet came out of. But that was pretty much it. And although portions of the 7th were relatively experienced with the sort of fight they were about to meet, roughly half the regiment had been stationed in the former Confederacy for the previous year and a half.

Archeological evidence suggests that many of the troopers who fought that day were not particularly healthy, either, their skeletal remains still retaining evidence of malnutrition and disease. Their sergeants weren’t the professional NCOs the U.S. Army expects its small-unit leaders to be. PVT Slaper of Company M recalled one of his recruit sergeants sending a group of newbies down to a saloon to trade their weapons and equipment for drink, and then sending a squad to “confiscate” the U.S. issue from the saloonkeeper, with the desired result being a whole bunch of happy, drunken soldiers.

Regardless of their training, health, or numbers, this little force was the fist at the end of the U.S. government’s arm, determined to force the “hostiles” back to imprisonment; approximately 600 to 650 regular medium cavalry under LTC George Armstrong Custer.

Native American tribal forces - The true number of native warriors who fought against Custer will probably never be known; the tribes were not innumerate, but the notion of precisely counting things like soldiers, well…

Native American tribal forces - The true number of native warriors who fought against Custer will probably never be known; the tribes were not innumerate, but the notion of precisely counting things like soldiers, well…

What we know is from the testimony of the white survivors and the recollections of the tribal witnesses. Bands from almost all the major north Plains tribes are known to have been present at the engagement; Northern Cheyenne, Arapaho, and at least seven Lakota groups; the Itázipčho (Sans Arc), Sihasapa (Blackfoot), Isáŋyathi (Santee), Brule, Miniconjoux, Oglala, and Hunkpapa. Some Wičhíyena (Yanktonai) and A'aninin (Gros Ventre) bands appear to have been present as well. Regardless of the social divisions it was an immense camp; several witnesses, both native and white, stated that the encampment along the Little Bighorn was the largest they had ever seen, containing well over 10,000 people and probably as many as 15,000.

However, the native groups camped along the Greasy Grass were all members of semi-nomadic, hunter-gatherer societies; only the arrival of the Europeans and their metallurgy had changed the technological level of the native peoples of North America from the Neolithic. Many of the tribes still lived in the ancient ways in 1876; a group living the life of a horse-nomadic people would not have had much surplus to devote to raising soldiers.

However, the native groups camped along the Greasy Grass were all members of semi-nomadic, hunter-gatherer societies; only the arrival of the Europeans and their metallurgy had changed the technological level of the native peoples of North America from the Neolithic. Many of the tribes still lived in the ancient ways in 1876; a group living the life of a horse-nomadic people would not have had much surplus to devote to raising soldiers.Instead, the military capability of the north Plains tribes lay in their young men, from the middle teens into the early fifties and possibly beyond for men of exceptional vigor, although a life lived outdoors, on horseback on the Great Plains, would have tired a guy out fairly early. The number of effectives present on 25 JUN was probably no more than 2-3,000 and very likely less, probably something like 1 in 10, so about 1,500 to 1,800.

The great capability of the Plains tribes was their horsemanship, their hardiness, and their bravery. A young Oglala man, or a Cheyenne warrior society soldier, would have known his land like the inside of his lodge, been a good shot with rifle or bow, strong, agile, and particularly deft at maneuvering mounted; no equivalent of the 7th’s hapless recruits would have been present on the native side unless you count some preadolescent boys and angry young women who joined in the fight.

But the great weakness of the tribes was their organization. There just wasn’t any, outside of the warrior societies, and even this was an informal sort of thing, hardly suited for battlefield tactics. Warriors fought as individuals, or in small groups.

Certain strong or charismatic leaders, men like Pizi (Gall), Ité Omáǧažu (Rain-in-the-Face), or Tȟašúŋke Witkó (“Crazy Horse”) might convince bands of warriors to follow them on specific movements or actions on the battlefield, but the notion of these leaders as planners, directors, or organizers of violence was inconceivable. There was no real “leader” for the tribes at the Little Bighorn, or, rather, there were dozens, hundreds, each one a Custer to his little group.

Certain strong or charismatic leaders, men like Pizi (Gall), Ité Omáǧažu (Rain-in-the-Face), or Tȟašúŋke Witkó (“Crazy Horse”) might convince bands of warriors to follow them on specific movements or actions on the battlefield, but the notion of these leaders as planners, directors, or organizers of violence was inconceivable. There was no real “leader” for the tribes at the Little Bighorn, or, rather, there were dozens, hundreds, each one a Custer to his little group. The best guess we can make is that approximately 1,500 to 2,000 irregular light cavalry rode out to meet the U.S. troops that day, under the leadership of many individuals; probably the best known of them is Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake, the man we know better as “Sitting Bull”.

The best guess we can make is that approximately 1,500 to 2,000 irregular light cavalry rode out to meet the U.S. troops that day, under the leadership of many individuals; probably the best known of them is Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake, the man we know better as “Sitting Bull”. Although this Hunkpapa elder was a respected spiritual leader and visionary, he was not a combat commander. Although his visions had led many to the valley of the Greasy Grass he was too frail to lead troops in 1876; he acted to help evacuate the women, children, aged, and ill during the fight.

Although this Hunkpapa elder was a respected spiritual leader and visionary, he was not a combat commander. Although his visions had led many to the valley of the Greasy Grass he was too frail to lead troops in 1876; he acted to help evacuate the women, children, aged, and ill during the fight.The Campaign: It’s probably fair to say that the “Great Sioux War of 1876-77” was just a campaign in the “Great European War of 1492-1890” that broke the power and the way of life of the native peoples in North America. But that would also be quite uninformative. The original causes of the war really stemmed from a collision between the native dwellers in the Black Hills and Powder River regions of the Dakotas and the American descendents of the European conquerors that began in the late 1860’s.

I originally had a long section here explaining the sequence of events that led up to the collision along the Little Bighorn. But you can read that elsewhere, and, really it was simple; the native peoples of part of North America had something that, in 1876, the white people who had already taken most of the continent wanted. The natives didn't want to "sell" (even if they had had the notion) and the whites didn't see why a bunch of "savages" should keep something they wanted. So they simply moved in and took it. The white men of 1876 literally couldn't imagine why anyone would leave "good land" - that is, land that could be logged, mined, or farmed - in the hands of what they saw as dirty, dangerous, shiftless animals who only used it to grub roots and hunt on.

I originally had a long section here explaining the sequence of events that led up to the collision along the Little Bighorn. But you can read that elsewhere, and, really it was simple; the native peoples of part of North America had something that, in 1876, the white people who had already taken most of the continent wanted. The natives didn't want to "sell" (even if they had had the notion) and the whites didn't see why a bunch of "savages" should keep something they wanted. So they simply moved in and took it. The white men of 1876 literally couldn't imagine why anyone would leave "good land" - that is, land that could be logged, mined, or farmed - in the hands of what they saw as dirty, dangerous, shiftless animals who only used it to grub roots and hunt on. Now, mind you, the loathing went both ways. And having the northern Cheyenne or the Lakota for neighbors wouldn't ever have been comfortable in the sense that a white American would have understood. The northern Plains tribes were horse nomads in the truest sense; they believed that they were Lords of Creation and that interlopers, strangers, or neighbors were to be treated with, traded with, robbed, or fought, as the spirit moved them. To the tribes, the whites were dangerous, weird, grabby assholes who were never willing to stay in their territory.

Now, mind you, the loathing went both ways. And having the northern Cheyenne or the Lakota for neighbors wouldn't ever have been comfortable in the sense that a white American would have understood. The northern Plains tribes were horse nomads in the truest sense; they believed that they were Lords of Creation and that interlopers, strangers, or neighbors were to be treated with, traded with, robbed, or fought, as the spirit moved them. To the tribes, the whites were dangerous, weird, grabby assholes who were never willing to stay in their territory. The collision was inevitable.

The collision was inevitable.But it would be the Black Hills that would bring things to a head. The U.S. government could have kept the settlers out, but it would have cost serious money and would have set the U.S. Army, which liked their neighboring horse nomads no more than the settlers did, against fellow whites. The federal government probably had doubts about whether an order to exclude whites from the Hills would have been obeyed.

Ironically, it was LTC Custer who was sent in to “explore” the Black Hills in 1874. This expedition reported the presence of gold in the Hills, and in a country being hammered by the Panic of 1873 that was enough to get the gold rush started. The Army did try and evict these claim jumpers from the Lakota lands, but all that did was increase the pressure on the Grant administration to try and come up with some sort of scheme to diddle the redskins out of their now-valuable property.

In May of 1875 a party of Lakota elders including Siŋté Glešká (Spotted Tail) of the Brule, Maȟpíya Lúta (Red Cloud) of the Oglala and Ha-wón-je-tah (Lone Horn) of the Minneconjou tried to convince Grant and his officials to honor the treaty. These worthies suggested that the Lakota leaders (who were not the “leaders” of the Lakota nation but merely notables and chiefs of certain groups – the U.S. government either never understood or chose not to acknowledge this, whichever was more profitable) take 25 grand and move to Oklahoma, perhaps the best attempted scam the Grant Administration (which was no piker where graft was concerned) ever tried.

In May of 1875 a party of Lakota elders including Siŋté Glešká (Spotted Tail) of the Brule, Maȟpíya Lúta (Red Cloud) of the Oglala and Ha-wón-je-tah (Lone Horn) of the Minneconjou tried to convince Grant and his officials to honor the treaty. These worthies suggested that the Lakota leaders (who were not the “leaders” of the Lakota nation but merely notables and chiefs of certain groups – the U.S. government either never understood or chose not to acknowledge this, whichever was more profitable) take 25 grand and move to Oklahoma, perhaps the best attempted scam the Grant Administration (which was no piker where graft was concerned) ever tried. Siŋté Glešká summed up the visitor’s reaction; “If it (this Oklahoma Territory the white men spoke so highly of) is such a good country, you ought to send the white men now in our country there and let us alone.”

Siŋté Glešká summed up the visitor’s reaction; “If it (this Oklahoma Territory the white men spoke so highly of) is such a good country, you ought to send the white men now in our country there and let us alone.”

The combination of lawless mining, other white encroachments such as the proposal to run the Northern Pacific railroad line through the main northern buffalo herd grazing lands, and the increasing drumbeat of violence caused by and directed at the Cheyenne had brought the tribes to a boiling point, while in Washington grave men met in quiet rooms to plan the destruction of a people.

In early November, 1875, Grant and his cabinet met with MG Sheridan, commander of the Division of the Missouri, and BG Crook, commander of the Department of the Platte to thrash out the U.S. government’s policy towards the Black Hills and the tribes surrounding them.

They agreed;

1. To stop the eviction of the miners; in effect, abrogating the Treaty of 1868.

2. To begin attacking and either capturing or killing members of the “hostile” or “non-treaty” bands of Lakota and northern Cheyenne unless they agreed to relocate to the Indian Agency stations for “council”.

An Indian Agency inspector by the name of Watkins couldn’t have liked this better. "The true policy in my judgement," he wrote, "is to send troops against them in the winter, the sooner the better, and whip them into subjection."

That fall the government sent instructions to their Indian agents in the Black Hills region that these “non-treaty” bands were required to report to their reservations by 31 JAN 1876 or else. The smarter agents realize that most of the bands not already on the agencies were snowed in for the winter, but by this time the Army was clearly spoiling for a fight. Phil Sheridan denied one agent’s request for more time. Sending little sticky notes out to the savages “…will in all probability be regarded as a good joke by the Indians."

In the winter lodges, the Lakota bands agreed that it was too late in the year to travel so far. They would winter in, hunt buffalo, and then move in the spring. It is likely, too, that the Lakota didn’t trust the story that everything was all happy and sunny now in the Black Hills. The “hostiles” stayed out of the agencies that winter.

In the winter lodges, the Lakota bands agreed that it was too late in the year to travel so far. They would winter in, hunt buffalo, and then move in the spring. It is likely, too, that the Lakota didn’t trust the story that everything was all happy and sunny now in the Black Hills. The “hostiles” stayed out of the agencies that winter. On 8 FEB 1876, MG Sheridan telegraphed his direction to BG Crook and BG Terry to initiate a winter campaigns against the "hostiles."

On 8 FEB 1876, MG Sheridan telegraphed his direction to BG Crook and BG Terry to initiate a winter campaigns against the "hostiles."Crook, as was his wont, move first. He sent a column of ten companies, five each from the 2nd and 3rd U.S. Cavalry, to raid a big winter camp along the Powder River in what is today Montana. The 300-some troopers slogged through the cold of a March night and took the encampment, a northern Cheyenne band led by Ó'kôhómôxháahketa (Little Wolf).

The entire affair was something of a fiasco. The troopers managed to drive the Cheyenne out of their village and managed to burn much of the lodges, food, and war materials within, but the bulk of the band escaped and even recaptured their horses, which the Army had seized but failed to guard securely. The Cheyenne warmaking ability was not seriously impaired, and no further military actions took place that winter and spring.

The entire affair was something of a fiasco. The troopers managed to drive the Cheyenne out of their village and managed to burn much of the lodges, food, and war materials within, but the bulk of the band escaped and even recaptured their horses, which the Army had seized but failed to guard securely. The Cheyenne warmaking ability was not seriously impaired, and no further military actions took place that winter and spring. Once the weather warmed enough to allow for regular troop movement Sheridan’s forces planned a triple envelopment of the “hostiles”. Crook would march north from Fort Fetterman, Terry west from Fort Lincoln, and COL Gibbon east from Fort Ellis, all converging on the Lakota and Cheyenne bands.

Once the weather warmed enough to allow for regular troop movement Sheridan’s forces planned a triple envelopment of the “hostiles”. Crook would march north from Fort Fetterman, Terry west from Fort Lincoln, and COL Gibbon east from Fort Ellis, all converging on the Lakota and Cheyenne bands. Terry’s part of the plan called for the 7th Cavalry (all his mobile force, really; the only other units under Terry’s command were two companies of the 17th Infantry and a machinegun (gatling) detachment) to “…proceed up the Rosebud in pursuit of the Indians whose trail was discovered by Major Reno…so as to preclude the escape of the Indians to the south or southeast by passing around to your flank. (I)t is hoped that the Indians, if upon the Little Horn, may be so nearly enclosed by (the Crook, Gibbon, and Terry) columns that their escape will be impossible.”

Terry’s part of the plan called for the 7th Cavalry (all his mobile force, really; the only other units under Terry’s command were two companies of the 17th Infantry and a machinegun (gatling) detachment) to “…proceed up the Rosebud in pursuit of the Indians whose trail was discovered by Major Reno…so as to preclude the escape of the Indians to the south or southeast by passing around to your flank. (I)t is hoped that the Indians, if upon the Little Horn, may be so nearly enclosed by (the Crook, Gibbon, and Terry) columns that their escape will be impossible.”What Gibbon, Terry, and Custer did not know was that Crook had run into a force of Lakota and Cheyenne along the south fork of the Rosebud on 17 JUN and had been badly mishandled.

This engagement is beyond the scope of this discussion, but Crook displayed a censurable neglect of simple tactical precautions including marching into enemy-held territory without adequate reconnaissance and security and then, once engaged, allowing his force to become divided, and allowing one of those elements to be isolated and mauled. Although the Army remained in possession of the field afterwards Crook and his command were knocked out of the campaign; they withdrew to the south and remained stationary for the following seven weeks.

This engagement is beyond the scope of this discussion, but Crook displayed a censurable neglect of simple tactical precautions including marching into enemy-held territory without adequate reconnaissance and security and then, once engaged, allowing his force to become divided, and allowing one of those elements to be isolated and mauled. Although the Army remained in possession of the field afterwards Crook and his command were knocked out of the campaign; they withdrew to the south and remained stationary for the following seven weeks.The remainder of the campaign, however, rolled on tracks as was the rule in pre-radio combat. Custer and Gibbon were to adhere to their timetables, and the movement to the meeting along the Greasy Grass began at midday on 22 JUN, 1876.

The Sources: The most frustrating part of the Little Bighorn is, as almost always in colonial war, the one-sided nature of the story.

To put it simply; there are no simple, easy-to-understand sources from the native participants.

To put it simply; there are no simple, easy-to-understand sources from the native participants.There are accounts, some written within a year or two but many from years afterwards and are affected by time and memory as you would expect. But the other problems with these accounts are legion. At first the warriors who had been at the Little Bighorn fight feared that they would be punished, and their tales are slanted to deflect that. Several are obviously intended to curry favor with the eventual victors of the Indian Wars.

Many more are riddled with the sorts of things common to preliterate, preindustrial peoples; lack of exact times, rearrangements of places and times, exactitude of detail in some portions, great vagueness in others. There is the question of translation, and whether the speaker was correctly understood.

Many more are riddled with the sorts of things common to preliterate, preindustrial peoples; lack of exact times, rearrangements of places and times, exactitude of detail in some portions, great vagueness in others. There is the question of translation, and whether the speaker was correctly understood.There is no single “best” source for native accounts; there is at least one website that appears to have a good variety of native American accounts of the battle as well as listing the participants as are known and their affiliations.

On the Army side, the survivors of Reno’s and Benteen’s units were interviewed, and there are the usual casualty lists and official reports. However, even here there are agendas, and care should be taken with soldier accounts.

On the Army side, the survivors of Reno’s and Benteen’s units were interviewed, and there are the usual casualty lists and official reports. However, even here there are agendas, and care should be taken with soldier accounts. For one thing, Custer’s partisans accused Reno and Benteen of various failings that led to the death of Custer and his unit; many accounts from the 7th Cavalry participants are slanted depending on which side of the Custer fan club they were on.

For example, 1LT Godfrey hated MAJ Reno, and every portion of his accounts of the engagement are designed to put Reno in a failing light. Likewise, CPT Benteen disliked LTC Custer (the 7th was not, as you can tell, an especially “happy” outfit) and his descriptions of the man and accounts of the battle are designed to detract from his former chief’s reputation. Here's the man himself, looking every bit the pugnacious bastard that his actions makes him to be.

For example, 1LT Godfrey hated MAJ Reno, and every portion of his accounts of the engagement are designed to put Reno in a failing light. Likewise, CPT Benteen disliked LTC Custer (the 7th was not, as you can tell, an especially “happy” outfit) and his descriptions of the man and accounts of the battle are designed to detract from his former chief’s reputation. Here's the man himself, looking every bit the pugnacious bastard that his actions makes him to be. And, for the record, here's MAJ Reno, also looking a bit like you'd expect him to be;

And, for the record, here's MAJ Reno, also looking a bit like you'd expect him to be; The earliest news and historical accounts of the fight are so hagiographic towards the cavalrymen as to be nearly meaningless.

The earliest news and historical accounts of the fight are so hagiographic towards the cavalrymen as to be nearly meaningless.

All natives are tricky and dangerous, all cavalrymen heroic and noble. It isn’t really until the middle of the 20th Century (because at that point all the participants were dead, in particular Elizabeth Custer, whose fierce attacks against anyone accusing her late husband of anything but brilliant leadership and heroic bravery put a chill on non-lauditory scholarship) until you start to see some less biased accounts of the day.

Two worthwhile non-primary sources are Evan S, Connell’s “Son of the Morning Star” (although Connell should be taken carefully on the subject of Custer himself; he apparently loathes the man and never passes up a Custer-bashing story regardless of provenance) and Richard Fox’s “Archaeology, History, and Custer’s Last Battle”, a truly intriguing work of scholarship produced after a range fire in the Eighties allowed Fox and his crew to perform a forensic study of physical evidence at the battle site, including tracking individuals through firearms analysis.

Although I don’t agree with all of Fox’s conclusions, his attempt to use the actual ground, the artifacts on it, and to integrate this with both American and native accounts is truly remarkable.

For general readers, the Osprey campaign series “Little Big Horn 1876” offers all the usual Osprey strengths in a very easily digestable format.

Perhaps the single most entertaining account of the affair is contaned in George McDonald Fraser’s “Flashman and the Redskins”, where the fictional ne’er-do-well is thrown in amongst the chaos along the Little Bighorn and, of course, turns out to be the only white man who rides down Medicine Tail Coulee with the Custer Battalion and survives. Of course. A fun read, and, within it's limits, good history.

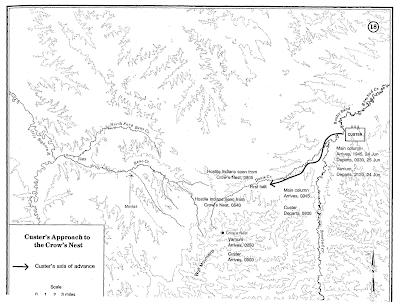

The Engagement: Custer’s force, the 7th U.S. Cavalry regiment – he had refused the 20th Infantry gatling detachment as too slow – departed Terry’s position near the mouth of the Rosebud at noon on 22 JUN and followed the river southwest for about four hours before bivouacking for the night. The following day, 23 JUN, the regiment moved a full day’s march up the Rosebud. The command had begun encountering sign that a large native force was up the river; a “large lodgepole trail” paralleled the river all the way up to the overnight spot of the 23-24 JUN.

(A brief note on Time. The officers of Terry’s expedition had “synchronized” their watches as much as hand-wound pocketwatches could be, at Terry’s HQ near St. Paul, MN. This is almost an hour ahead of the local time along the Little Bighorn, and there appears to be considerable room for disagreement on exactly when things happened on 25 JUN. I will generally adhere to the commonly cited event times, although when there is a controversy I will mention it.)

(A brief note on Time. The officers of Terry’s expedition had “synchronized” their watches as much as hand-wound pocketwatches could be, at Terry’s HQ near St. Paul, MN. This is almost an hour ahead of the local time along the Little Bighorn, and there appears to be considerable room for disagreement on exactly when things happened on 25 JUN. I will generally adhere to the commonly cited event times, although when there is a controversy I will mention it.) The following day (24 JUN) the cavalry continued up the Rosebud, encountering more and fresher signs of recent native occupation, including a recently abandoned village site, and went into bivouac about two miles northeast of the forks of the Rosebud. The halt was a brief one; the command was moving again near midnight and marched another several miles in the dark before halting at daylight.

The following day (24 JUN) the cavalry continued up the Rosebud, encountering more and fresher signs of recent native occupation, including a recently abandoned village site, and went into bivouac about two miles northeast of the forks of the Rosebud. The halt was a brief one; the command was moving again near midnight and marched another several miles in the dark before halting at daylight. That night the scouting detachment had moved to a place called “The Crow’s Nest” in the Wolf Mountains that lie between the valleys of the Bighorn and the Rosebud rivers. On the morning of 25 JUN LTC Custer climbed to the summit of this eminence to talk to the Crow and Ree scouts of what they had seen of his enemies.

That night the scouting detachment had moved to a place called “The Crow’s Nest” in the Wolf Mountains that lie between the valleys of the Bighorn and the Rosebud rivers. On the morning of 25 JUN LTC Custer climbed to the summit of this eminence to talk to the Crow and Ree scouts of what they had seen of his enemies. The scouts told him that they had seen a village, a large encampment, down in the valley of the Little Bighorn River some 15 to 20 miles to the northwest. They had seen the large pony herd wriggling “like worms”, as well. LT Varnum reported that he had not seen these things, but that the Crows were certain they were there. Worse, he also reported that his detachment had seen natives, hunters, stragglers, or perhaps scouts, in the vicinity of the Crow’s Nest. They had pursued these men but had not captured them. This, by the way, is the modern view from Crow's Nest; it must have been very like this on the morning of 25 JUN 1876.

The scouts told him that they had seen a village, a large encampment, down in the valley of the Little Bighorn River some 15 to 20 miles to the northwest. They had seen the large pony herd wriggling “like worms”, as well. LT Varnum reported that he had not seen these things, but that the Crows were certain they were there. Worse, he also reported that his detachment had seen natives, hunters, stragglers, or perhaps scouts, in the vicinity of the Crow’s Nest. They had pursued these men but had not captured them. This, by the way, is the modern view from Crow's Nest; it must have been very like this on the morning of 25 JUN 1876. All this news of roaming injuns and compromised security must have been an unpleasant surprise to LTC Custer. He seems to have hoped that he could conceal the regiment in the folded ground around the Wolf Mountains for 25 JUN and emerge the following day to link up with Gibbon and Crook. But if the “hostiles” had spotted a large force of cavalry this plan was unlikely to work.

All this news of roaming injuns and compromised security must have been an unpleasant surprise to LTC Custer. He seems to have hoped that he could conceal the regiment in the folded ground around the Wolf Mountains for 25 JUN and emerge the following day to link up with Gibbon and Crook. But if the “hostiles” had spotted a large force of cavalry this plan was unlikely to work. The Army of 1876 was obsessed with the idea that native forces would escape them. The Plains tribes’ greater mobility and knowledge of the terrain made them nearly impossible to capture or destroy if they chose to disengage. So the news that the 7th had been sighted would have been the worst possible; the native bands would at that moment be hatting out, disappearing into the landscape, and that would mean more long, dusty marching and endless valley-hunting. That was not what the commander, and the troopers, were here for.

The Army of 1876 was obsessed with the idea that native forces would escape them. The Plains tribes’ greater mobility and knowledge of the terrain made them nearly impossible to capture or destroy if they chose to disengage. So the news that the 7th had been sighted would have been the worst possible; the native bands would at that moment be hatting out, disappearing into the landscape, and that would mean more long, dusty marching and endless valley-hunting. That was not what the commander, and the troopers, were here for.One major factor at work here was that the Army forces in the field in the summer of 1876 were completely misinformed about the huge number of “hostile” bands they were attempting to subdue.

The Indian agents had been misreporting, either through ignorance or deliberate evasion, the number of bands that either had refused to come into the agencies at all or had left in late spring for the summer buffalo hunts. The “official” number of tribesmen reported to be out was 800.

The Indian agents had been misreporting, either through ignorance or deliberate evasion, the number of bands that either had refused to come into the agencies at all or had left in late spring for the summer buffalo hunts. The “official” number of tribesmen reported to be out was 800. So probably foremost in the mind of LTC Custer that morning was what he saw as the imperative to prevent the natives from scattering and escaping, and the relatively small force at their disposal. His scheme of maneuver reflects his priorities; he divided the regiment into three roughly battalion-sized elements.

So probably foremost in the mind of LTC Custer that morning was what he saw as the imperative to prevent the natives from scattering and escaping, and the relatively small force at their disposal. His scheme of maneuver reflects his priorities; he divided the regiment into three roughly battalion-sized elements. Three companies (A, G, and M) were placed under the command of MAJ Marcus Reno and tasked to make a fixing attack on the village from the 7th’s position to the southeast. Three more (D, H, and K)were placed under the command of CPT Frederick Benteen and ordered to maneuver to the regiment’s left, west and south, to cut off escape in that direction. The regimental commander kept five companies (C, E, F, I, and L) under his hand to maneuver to the regimental right, along the high bluffs to the east of the village, presumably to encircle the encampment and bag the enemy before they could escape. Company B, CPT Thomas McDougald commanding, was detailed to escort the regimental trains.

Given the S-2 briefing he had received and his perceived understanding of his mission I understand Custer’s division of his forces. I don’t see it as carelessness or recklessness, but rather the “conventional” or school solution to the problem he was faced with. LTC Custer was considered very “dashing”, a real 19th Century Murat-style cavalry plunger. No one who knew him ever described him as a commander of exceptional tactical skill or perception. And his actions at the Greasy Grass confirmed the conventional assessment.

A genuinely gifted commander might have wondered about the immense encampment his scouts reported or he observed when his command closed on the river valley, and might have heard something in the voices of the men more familiar with the tribes.

One of his white scouts, Mitch Bouyer, is said to have told him “General, I have been with these Indians for 30 years, and this is the largest village I have ever heard of.” Most versions of the story have the Crow and Ree scouts ripping off their hand-me-down uniform shirts so that they could die as warriors; supposedly Custer was so insulted when these men began to sing their “death songs” that he dismissed them from their service on the spot.

But he does not seem to have wondered why these tough fighters were suddenly so convinced that 25 JUN was their last day. And he does not seem to have grasped the enormity of his task, or the nature of his enemy. His plan, from what his unit assignments tell us, was not really an attack plan at all, but a sort of vague reconnaissance-in-force, designed to find and fix an elusive enemy that he expected to run away.

Seldom has a commander been quite so mistaken.

The regiment had moved forward from the Crow’s Nest in fits and starts, and by noon (about 10:00 local sun time) were still about 10-12 miles east of the village at the point where Custer divided his command. For the next three hours the cavalry advanced generally west; the eight companies of Reno and Custer directly west along what would become known as “Reno Creek”, Benteen with his three-company element to the southwest.

The Custer-Reno units arrived at the east bank of the Little Bighorn River about 1500hrs. Here Custer repeated his instructions to Reno and is supposed to have told the major to ride into the village, that his attack would be “supported by the whole outfit”. Reno marshaled his troops for a mounted attack and Custer’s unit moved out to the northwest, along the bluffs east of the river.

The Custer-Reno units arrived at the east bank of the Little Bighorn River about 1500hrs. Here Custer repeated his instructions to Reno and is supposed to have told the major to ride into the village, that his attack would be “supported by the whole outfit”. Reno marshaled his troops for a mounted attack and Custer’s unit moved out to the northwest, along the bluffs east of the river. Reno’s assault ran into immediate trouble.

Reno’s assault ran into immediate trouble. Far from running, the Cheyenne, Lakota, and Arapaho came at Reno’s little command – no more than 180 troopers at most – hard and forced the cavalry to dismount to attempt to suppress the tribesmen with fire. This may have worked for a moment, but the warriors quickly worked around the open ground on Reno’s left. Reno’s firing halt had come at about 1520; within ten minutes the major ordered a retrograde movement into the stand of timber to the battalion’s right.

Far from running, the Cheyenne, Lakota, and Arapaho came at Reno’s little command – no more than 180 troopers at most – hard and forced the cavalry to dismount to attempt to suppress the tribesmen with fire. This may have worked for a moment, but the warriors quickly worked around the open ground on Reno’s left. Reno’s firing halt had come at about 1520; within ten minutes the major ordered a retrograde movement into the stand of timber to the battalion’s right. The defense of this position lasted less than half an hour.

The defense of this position lasted less than half an hour.By 1600 Reno ordered his battalion to retire to the bluffs they had started from.

This retreat was a disaster.

This retreat was a disaster.The unit, not well-controlled in advance, fell apart in retreat. George Herendeen, one of Reno’s civilian scouts, said of the fiasco;

“The command headed for the ford, pressed closely by Indians in large numbers, and at every moment the rate of speed was increased, until it became a dead run for the ford. The Sioux, mounted on their swift ponies, dashed up by the side of the soldiers and fired at them, killing both men and horses. Little resistance was offered, and it was a complete rout to the ford.”Still, the bulk of Reno’s command regained the east bank of the Little Bighorn. There they formed a defensive perimeter and fortified it as best they could, scraping rifle pits with butts or knives, using saddles or dead horses.

CPT Benteens’ element had found nothing in their “valley-hunting” as Benteen disgustedly described it later. Some time around 1400 to 1500 Benteen turned northwest and rejoined the main force route, coming upon Reno’s group some time between 1600 and 1700 in time to join the defense on the bluffs. The reunited battalions hunkered down under harassing fire and occasional small-group rushes until the fighting ended in darkness about 2100.

CPT Benteens’ element had found nothing in their “valley-hunting” as Benteen disgustedly described it later. Some time around 1400 to 1500 Benteen turned northwest and rejoined the main force route, coming upon Reno’s group some time between 1600 and 1700 in time to join the defense on the bluffs. The reunited battalions hunkered down under harassing fire and occasional small-group rushes until the fighting ended in darkness about 2100. The attacks continued the following day, 26 JUN, and were not mere harassment; Reno is said to have lost as many as half of his total of 36 KIA in the defense of his position on 26 JUN. Benteen’s battalion lost another 12 KIA on the bluffs, and three men from McDougald’s B Company were killed there, as well. This “siege” continued though gradually diminished throughout the day until the troopers watched the massive village move away toward the Bighorn Mountains to the west. The seven companies were still in place when Gibbon’s troops arrived on 27 JUN to relieve them.

The attacks continued the following day, 26 JUN, and were not mere harassment; Reno is said to have lost as many as half of his total of 36 KIA in the defense of his position on 26 JUN. Benteen’s battalion lost another 12 KIA on the bluffs, and three men from McDougald’s B Company were killed there, as well. This “siege” continued though gradually diminished throughout the day until the troopers watched the massive village move away toward the Bighorn Mountains to the west. The seven companies were still in place when Gibbon’s troops arrived on 27 JUN to relieve them. Far from supporting anyone on 25 JUN, Custer’s five companies had completely disappeared.

Far from supporting anyone on 25 JUN, Custer’s five companies had completely disappeared.Troopers in the Reno/Benteen command had some ideas as early as the day of the engagement that something had gone badly wrong with Custer’s command. The last sight anyone had had of them was at about 1515, when Reno’s troopers had seen Custer himself and his troops riding parallel to their attack along the east bank of the River and disappearing over the bluffs.

At about 1620 or 1630 several white witnesses say that they began to hear heavy firing downstream of the Reno position. This firing grew in intensity, with some men claiming that they heard organized volley firing, until by 1655 CPT Weir, D Co., commanding, requested that his company move north to assist the Custer unit.

He did so about 1700, but in the roughly fifteen minutes it took him to ride to what is today “Weir Point” (the furthest north position on the Reno defense position bluff that overlooks today’s Custer Battlefield) the firing is reported to have died down. By 1715 Weir and his troops report seeing only native warriors policing the area and firing “into the ground”. Even though he is joined by CPT Benteen’s three companies the units are then driven under pressure back to the original defense position.

He did so about 1700, but in the roughly fifteen minutes it took him to ride to what is today “Weir Point” (the furthest north position on the Reno defense position bluff that overlooks today’s Custer Battlefield) the firing is reported to have died down. By 1715 Weir and his troops report seeing only native warriors policing the area and firing “into the ground”. Even though he is joined by CPT Benteen’s three companies the units are then driven under pressure back to the original defense position.Neither Custer nor anyone of his command joins them during the remainder of the day or on the next.

And, of course, we know why. LTC Custer and every man in his five companies had been killed on the high bluffs east of the Little Bighorn, the worst U.S. Army defeat at the hands of native forces since the Battle of the Wabash in 1791.

Two hundred and ten bodies were scattered across the rolling hills above the Little Bighorn. LTC Custer and four of his command staff. Every cavalrymen of the five line companies, a total of 199 KIA. A journalist. Six other civilians, variously described as “packers”, “interpreters”, or “guides”, including among them Custer’s 22-year-old brother Boston and 18-year-old nephew “Autie” Reed, who couldn’t between them have guided a seeing-eye dog around the valley of the Little Bighorn – they were combat tourists pure and simple.

Two hundred and ten bodies were scattered across the rolling hills above the Little Bighorn. LTC Custer and four of his command staff. Every cavalrymen of the five line companies, a total of 199 KIA. A journalist. Six other civilians, variously described as “packers”, “interpreters”, or “guides”, including among them Custer’s 22-year-old brother Boston and 18-year-old nephew “Autie” Reed, who couldn’t between them have guided a seeing-eye dog around the valley of the Little Bighorn – they were combat tourists pure and simple.The sole “survivor” found by the soldiers amid the bodies that littered the places we now call “Nye-Cartwright Ridge”, “Last Stand Hill”, and “Deep Ravine” was CPT Keogh’s bay gelding “Comanche”.

The Controversy: Almost as soon as the last dead man dropped the controversies surrounding this engagement began.

The Controversy: Almost as soon as the last dead man dropped the controversies surrounding this engagement began.Part of this was because of the defeat of a “civilized” force by “savages”; there HAD to be some explanation beyond “sometimes you win, sometimes you lose…” – someone had to be to blame, some mistake or set of circumstances that explained why the white soldiers lost (rather than the native warriors won).

Part of this was the nature of the commander. George Armstrong Custer was a divisive sort of man and a polarizing sort of officer. He had many supporters and friends to whom he could do nothing wrong, and he had many enemies and skeptics who considered him foolish at best and actively dangerous at worst.

So very soon, possibly even while the unit was in the field, his officers were picking up sides.

There was one faction – 1LT Godfrey is among them – that tended to blame the entire fiasco on the subordinates; Benteen for one, but mostly Reno. In their way of thinking if Reno had attacked as Custer intended the hostiles would not have been able to concentrate on the northern elements and Custer’s plan would have worked. Their argument was that Custer was a genius betrayed by the cowardice and incompetence of little men.

The other faction, which obviously included Reno and Benteen, held that there was no “plan”; that Custer had divided his force in the face of overwhelming enemy strength to no purpose, and that if Reno had not acted to save his force it, too, would have disappeared somewhere in the Little Bighorn valley as part of the piecemeal destruction of the regiment. Their argument was that Custer was a glory-hungry fool whose incompetence would have gotten more men killed if his decisions had been carried out.

The other faction, which obviously included Reno and Benteen, held that there was no “plan”; that Custer had divided his force in the face of overwhelming enemy strength to no purpose, and that if Reno had not acted to save his force it, too, would have disappeared somewhere in the Little Bighorn valley as part of the piecemeal destruction of the regiment. Their argument was that Custer was a glory-hungry fool whose incompetence would have gotten more men killed if his decisions had been carried out.Perhaps the single issue that keeps the Battle of the Little Bighorn written and argued over is the subject of the “last stand”.

When the news of the defeat broke over a nation celebrating its centennial the immediate, and for many, many years the only, reaction was one of horror at the “massacre” and hagiography of the dead men. The nefarious redskins had obviously overwhelmed the cavalrymen with human wave tactics, soaking up the bullets of the hard-bitten troopers until they were buried beneath the savage hordes.

Pictures, paintings, stories, plays, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show…eventually movies such as this one; “They Died With Their Boots On”, where Errol Flynn thrilled 1941 audiences with his noble fight-to-the-last-round-and-last-man heroics. There could be no doubt. The 7th Cavalry had fought, and died, like heroes, a tribute to their nation and the white American civilization they represented.

Pictures, paintings, stories, plays, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show…eventually movies such as this one; “They Died With Their Boots On”, where Errol Flynn thrilled 1941 audiences with his noble fight-to-the-last-round-and-last-man heroics. There could be no doubt. The 7th Cavalry had fought, and died, like heroes, a tribute to their nation and the white American civilization they represented. That there were darker tales, of panic, disorganization, and disintegration could only be the foolish tales of unenlightened savages. The United States of 1876 had no ear for such stuff. They wanted a tale of heroics, and that taste for heroes has colored the most widespread version of Custer’s fate still extant.

That there were darker tales, of panic, disorganization, and disintegration could only be the foolish tales of unenlightened savages. The United States of 1876 had no ear for such stuff. They wanted a tale of heroics, and that taste for heroes has colored the most widespread version of Custer’s fate still extant. This tale, the “heroic”, or “fatalistic” version, has the cunning savages lying in wait for Custer in overwhelming force. After the Custer battalion rides north of the bluffs where Reno’s men see them they supposedly turn down to the west and ride down to the bottom of Medicine Tail Coulee. Here they try to cross but are met with a hurricane of fire that drives them back up into the hills, where Gall and Crazy Horse are waiting. The doomed troopers fort up on Last Stand Hill and fight until they are overwhelmed.

This tale, the “heroic”, or “fatalistic” version, has the cunning savages lying in wait for Custer in overwhelming force. After the Custer battalion rides north of the bluffs where Reno’s men see them they supposedly turn down to the west and ride down to the bottom of Medicine Tail Coulee. Here they try to cross but are met with a hurricane of fire that drives them back up into the hills, where Gall and Crazy Horse are waiting. The doomed troopers fort up on Last Stand Hill and fight until they are overwhelmed. To my mind there are two significant problems with this story.

To my mind there are two significant problems with this story.First, it doesn’t really fit the archaeological evidence.

In Fox’s “Archaeology, History, and Custer’s Last Battle” the author carefully reconstructs the events of 25 JUN as revealed through modern finds of bullets, cartridge cases, and other artifacts. He doesn’t find any evidence for a climactic firefight around Last Stand Hill; in fact, there are very few Springfield or Colt cartridge cases (indicating Army firing) relative to, say, the Company L skirmish position at the south end of Battle Ridge, the so-called “Calhoun Hill”. The soldiers who died at the more famous hill, as well as the soldiers who died along the ridge that runs up to there from Calhoun Hill to the south, appear to have died with surprisingly little firing on their part.

To summarize the author’s conclusions, the archaeological evidence suggests that the Custer battalion was operating in two wings at the time it was overrun. One wing, presumably Companies C, I, and L led by CPT Keogh, was stationed near the south end of Battle Ridge, near Calhoun Hill skirmishing against enemies to the south and west. The other, Companies E and F, were to the north somewhere; possibly attempting to find another way across the river, possibly attempting to hold off other enemies approaching from the north or northwest. Fox believes the former; that Custer was continuing north, attempting to find a way to completely encircle the immense village.

To summarize the author’s conclusions, the archaeological evidence suggests that the Custer battalion was operating in two wings at the time it was overrun. One wing, presumably Companies C, I, and L led by CPT Keogh, was stationed near the south end of Battle Ridge, near Calhoun Hill skirmishing against enemies to the south and west. The other, Companies E and F, were to the north somewhere; possibly attempting to find another way across the river, possibly attempting to hold off other enemies approaching from the north or northwest. Fox believes the former; that Custer was continuing north, attempting to find a way to completely encircle the immense village. The warriors WERE encircling Custer, but they were doing so in defilade, moving as individuals and in small groups, and the size of the force opposing him was not apparent to Custer.

The warriors WERE encircling Custer, but they were doing so in defilade, moving as individuals and in small groups, and the size of the force opposing him was not apparent to Custer.Fox’s theory is that Keogh sent one of his companies (Fox theorizes C) on a mounted charge downhill to the west. He believes that this charge was met with an ambush – Lame White Man’s attack – and was decimated by overwhelming fire shock and retired in confusion. He believes that the Cheyenne warriors pursued Company C into the Company L firing line and overwhelmed it.

At this time an attack may have also come from the east (“Crazy Horse’s attack”), which helped break the Company L horses loose and exacerbate the rout, sending a disorganized mass of panicked and desperate men back into the battalion reserve Company I, which in turn broke and ran with the mass north in an attempt to join Companies E and F, which Fox believes were at that time near Last Stand Hill and in the upper reaches of Deep Ravine to the west. These two companies were, in turn, thrown into disorder and quickly butchered, the last victims fleeing eastward into Deep Ravine where they were knocked on the head to end the Custer battle.

At this time an attack may have also come from the east (“Crazy Horse’s attack”), which helped break the Company L horses loose and exacerbate the rout, sending a disorganized mass of panicked and desperate men back into the battalion reserve Company I, which in turn broke and ran with the mass north in an attempt to join Companies E and F, which Fox believes were at that time near Last Stand Hill and in the upper reaches of Deep Ravine to the west. These two companies were, in turn, thrown into disorder and quickly butchered, the last victims fleeing eastward into Deep Ravine where they were knocked on the head to end the Custer battle. This is Fox’s theory, mind you. Reading his work, I don’t think the evidence supports all of his conclusions. But there does seem to be a significant lack of physical evidence supporting a fierce, organized resistance, and that leads to the second reason I don’t buy the “fatalistic” version; the Reno/Benteen Defense.

This is Fox’s theory, mind you. Reading his work, I don’t think the evidence supports all of his conclusions. But there does seem to be a significant lack of physical evidence supporting a fierce, organized resistance, and that leads to the second reason I don’t buy the “fatalistic” version; the Reno/Benteen Defense. Seven companies, a little over half the regiment, having (in the case of A, G, and M Companies, at least) already been badly whipped and driven off in panic, low on food and water, caring for many wounded, managed to hold off the entire armed might of the Cheyenne, Lakota, and Arapaho bands for a day and a half, losing about 50 troopers total, probably no more than 40 in the actual defense. And yet Custer with his five companies is driven into a hasty defense and is overrun in less than an hour, losing over 200 men?

Seven companies, a little over half the regiment, having (in the case of A, G, and M Companies, at least) already been badly whipped and driven off in panic, low on food and water, caring for many wounded, managed to hold off the entire armed might of the Cheyenne, Lakota, and Arapaho bands for a day and a half, losing about 50 troopers total, probably no more than 40 in the actual defense. And yet Custer with his five companies is driven into a hasty defense and is overrun in less than an hour, losing over 200 men?That doesn’t seem to make much sense, does it?

Here’s what I think happened.

I don’t think there’s any way to tell exactly what Custer’s movements were. But I think that, knowing the man, knowing his mission, knowing what he thought his enemy’s most dangerous course of action (a tactical retreat to avoid combat) was, that he was maneuvering offensively. I think he dropped Keogh’s battalion on Calhoun Hill and took Yates’ battalion north, looking for a better avenue of approach to the big village.

I think that while Companies E and F were caprioling around Last Stand Hill and north the warriors to the south used stealth tactics to get close to the skirmishing Company L, and then overwhelmed it and Company C with fire shock and close assault. I think that the much of the Keogh battalion came apart; that while individuals fought many others did not. That is, that organized resistance as a military unit ceased rapidly even while individual or small unit fights may not have.

I think that while Companies E and F were caprioling around Last Stand Hill and north the warriors to the south used stealth tactics to get close to the skirmishing Company L, and then overwhelmed it and Company C with fire shock and close assault. I think that the much of the Keogh battalion came apart; that while individuals fought many others did not. That is, that organized resistance as a military unit ceased rapidly even while individual or small unit fights may not have.That the resulting chaos was driven north as some troopers either attempted to flee, surrender, or simply cowered in the way that soldiers have been known to in the extremes of panic and fear, simply waiting passively for death.

I think that Yates’ battalion was probably overrun the same way; possibly Company F was skirmishing from Last Stand Hill where they watched, horrified, as the Keogh wing came unglued. The running fight from the south laps into them.

I think that Yates’ battalion was probably overrun the same way; possibly Company F was skirmishing from Last Stand Hill where they watched, horrified, as the Keogh wing came unglued. The running fight from the south laps into them.Perhaps it was then that Tȟašúŋke Witkó boiled up from the north or east and slammed into them. They may have fired a hasty spatter of shots, but the notion of volleys seems risible - the open order of the Army skirmish line and the chaotic individual tactics of the warriors makes volley firing both wasteful and ineffective - and then many of them were killed on the spot.

What was left of Company E and the fugitives of the rest of the battalion was hunted down into the Deep Ravine valley.

Many individual fights, perhaps, or a squad or a small group, but no organized resistance by the troopers.

Many individual fights, perhaps, or a squad or a small group, but no organized resistance by the troopers. Reed Horse of the Minnecoujou described it:

“…the Sioux charged (Custer's) soldiers below, and drive them in confusion; these soldiers became foolish, many throwing away their guns and raising their hands, saying, "Sioux, pity us; take us prisoners." The Sioux did not take a single soldier prisoner, but killed all of them; none were left alive for even a few minutes. These different soldiers discharged their guns but little.”Runs the Enemy of the Oóhe Núŋpa Lakota drew a picture of the rout from Calhoun Hill to Last Stand Hill;

“Another charge was made and they retreated along the line of the ridge; it looked like a stampede of buffalo.”I believe that Custer’s command died as he did; baffled and confused about what was happening to them, suddenly shocked by the ferocity of the Cheyenne and the Lakota, attempting but incapable of making any serious organized resistance.

This does not make them any less brave; any man who forked a horse that morning was a brave man by my standards. But it does explain how quickly the Custer unit perished, and goes a long way to explain the last great fighting day of the Lakota and Cheyenne nations.

This does not make them any less brave; any man who forked a horse that morning was a brave man by my standards. But it does explain how quickly the Custer unit perished, and goes a long way to explain the last great fighting day of the Lakota and Cheyenne nations.The Outcome: Tactical Cheyenne/Lakota victory.

The Impact: Negligible.

In a very real sense, the Cheyenne and the Lakota gained nothing from their victory but grief. Most of the “hostiles” had surrendered to the agencies within a year. A handful of diehards fled to Canada, but when the buffalo there were hunted out conflicts with the First Nations tribes forced many of them to return in the 1880s.

In a very real sense, the Cheyenne and the Lakota gained nothing from their victory but grief. Most of the “hostiles” had surrendered to the agencies within a year. A handful of diehards fled to Canada, but when the buffalo there were hunted out conflicts with the First Nations tribes forced many of them to return in the 1880s.Tȟašúŋke Witkó was murdered in September of the following year, Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake in the Ghost Dance year of 1890. The great northern Plains tribes were largely confined by the Eighties, and were broken for good in the 1890s, since when they have been confined to the white man’s world and their “reservations”, slowly dying of inconsequence and alcohol.

The ranks of the cavalry dead were replaced before the end of the year. The 7th Cavalry went on to play a long role in the closing of the Western frontier, including the last act in the Ghost Dance period of 1890, firing the shots at Wounded Knee that helped finish the Lakota people as a sovereign entity and a distinct culture.

The ranks of the cavalry dead were replaced before the end of the year. The 7th Cavalry went on to play a long role in the closing of the Western frontier, including the last act in the Ghost Dance period of 1890, firing the shots at Wounded Knee that helped finish the Lakota people as a sovereign entity and a distinct culture. All civilizations believe that they are unique and worthy, and better than anyone else's. Had the Cheyenne been fortunate enough to have discovered gunpowder, steel, and several epidemic diseases and been bitten by the conquest bug they would very likely have happily conquered Europe and exterminated the Britons and the French as the descendants of those Europeans did them.

All civilizations believe that they are unique and worthy, and better than anyone else's. Had the Cheyenne been fortunate enough to have discovered gunpowder, steel, and several epidemic diseases and been bitten by the conquest bug they would very likely have happily conquered Europe and exterminated the Britons and the French as the descendants of those Europeans did them.

This wasn’t the question of a noble savage and a rapacious invader; this was two tough, smart, ambitious cultures that both wanted the same piece of real estate. The invader just happened to have better technology and social organization, and no place in his society for a group of seminomadic tribes.

The settled man has always hated and feared the nomad. When horse peoples have collided with settled peoples there has always been violence, from the steppes of Russia to north China to the prairies of North America. The end of the native American story is a tragedy for them, but not a tragedy unique to them.

If the Little Bighorn says anything about this, it is simply that the United States was simply too vast, too well organized, too implacably convinced of its own rightness – its “manifest destiny” to rule the continent – for the Plains tribes to deflect. They tried living with us, they tried fighting us…and they even beat us, most famously that hot, dusty afternoon along the slopes of the Greasy Grass.

But it wasn’t enough and would never be enough. The Cheyenne, the Lakota, just like the Aztec and the Seminole and the Cherokee before them, were individuals, families, bands, perhaps tribes. They were simply too vulnerable to epidemic disease, too far behind the industrial power-curve. Had ALL the tribes combined, embarked on an immediate program of industrialization and agriculture, AND had the benefit of a caesura in the white drive to the west...well, you can tell from that the impossibility of it all.

But it wasn’t enough and would never be enough. The Cheyenne, the Lakota, just like the Aztec and the Seminole and the Cherokee before them, were individuals, families, bands, perhaps tribes. They were simply too vulnerable to epidemic disease, too far behind the industrial power-curve. Had ALL the tribes combined, embarked on an immediate program of industrialization and agriculture, AND had the benefit of a caesura in the white drive to the west...well, you can tell from that the impossibility of it all.The native peoples were doomed.

Touchline Tattles: There’s not much lightness about the day, really. Even the “humorous” tales from the engagement have a grim flavor to them, like the cartoon Irish cavalryman so thirsty for drink that he jokes with the surgeon that he’ll have his other leg off if it will get him some more booze. There's a tragic, doomed taste to the whole business.

Perhaps the best assessment of the day comes from our fictional friend Flashman, whose author puts into the mouth of one of his “redskins” the observation that regardless of the bigger picture, regardless of rights and wrongs, regardless of who were the defenders and invaders, of who did what to who, what was certain is that the troopers of the 7th Cavalry had come looking for trouble on the banks of the Little Bighorn and they surely found it on there, along the lonely high bluffs east of the river, where when the last of the tourist buses chuffs away only the wind and the evening song of the meadowlark speak to the graves of the men who died, and the way of life that died with them.

Perhaps the best assessment of the day comes from our fictional friend Flashman, whose author puts into the mouth of one of his “redskins” the observation that regardless of the bigger picture, regardless of rights and wrongs, regardless of who were the defenders and invaders, of who did what to who, what was certain is that the troopers of the 7th Cavalry had come looking for trouble on the banks of the Little Bighorn and they surely found it on there, along the lonely high bluffs east of the river, where when the last of the tourist buses chuffs away only the wind and the evening song of the meadowlark speak to the graves of the men who died, and the way of life that died with them.

26 comments:

Nicely researched as always.

Why did you choose Little Bighorn? It certainly wasn't decisive, more a speed-bump in the road to Manifest Destiny.

National Geographic did a similar article a few months back (I don't recall the exact conclusions but they are similar to yours).

I think I wrote about this in the "battle" for March, Pancho Villa's raid on Columbus; I've gotten to the point where I'm running out of "decisive" battles that interest me (I just don't want to write about, say, Fontenoy) or that I have anything of value to contribute (I have nothing to say about Stalingrad that hasn't been said a jillion times over, so what would be the point?). So I've started writing about battles that just interest me, or ones that had an impact far out of proportion with the actual engagement itself (like Columbus) or, as in this case, have taken on a life of their own outside the historical facts of the engagement.

That last is where the LBH falls; there's a "mythic" LBH that was created almost immediately after the battle ended that endures to this day, and resists any attempt to revisit the sort of combat actions that would have resulted in the deaths of over 200 soldiers in 45 minutes with minimal loss to their enemies.

So for this one, it's the "controversial" part that interests me. In terms of effect on the white conquest of NA, not even a speed bump - more like grit under the tires.

Thanks kindly Chief, I always enjoy your articles.

Have you considered writing about the Battle of Sekigahara? It is an interesting battle where the maneuvering (in the largest sense) before the battle was extremely important.

Hi Chief, nice article. I agree that most of the "decisive" battles have been covered now. Maybe it's time to change this to "Battles That Interest Me".

My understanding of 'Custer's Last Stand' comes from John Keegan's book "Fields of Battle: The Wars for North America". He follows John Gray who thinks Custer continued to attack, even when getting information that the number of natives was much larger, confident that firepower and discipline would prevail. By the time he realized that this was too many aboriginals for he units firepower to stop, it was too late.

Gray thinks Custer tried to form a defensive position at the best terrain Custer had (which it wasn't) but was far too wide for his command. This left a thin defensive line that would never be able to put out the volume of fire to suppress the warriors. Eventually they found weak-points and gaps, broke through and history takes it's sorry end.

Actually I'd also recommend looking at battles that are significant in some way but are oft-overlooked for various reasons. I seem to remember you covered one of the battles of the Russo-Finnish war (I may be wrong, I couldn't find it in your archives). If not, mayhaps Tali-Ilhantala, the battle that saved Finland from becoming a Soviet satellite. Or maybe something more ancient: Zama, Alesia, etc...

Ael: I've thought about several of the battles from the Japanese feudal period, but I think the one I will write up this September is the Battle of Shiroyama, 1877. It has it all; Samurai, cannon, seppuku, Tom Cruise...(wait, no, sorry).

Leon: The Winter War has some good stuff, but you're right in that the 1944 battles of the Continuation War were truly critical in saving an independent Finland. I think I might writeup the Battle of Ilomantsi for July this year. Great story, with the Finns bitchslapping the Soviet bear...again.

Another cracking article chief, stick with the (not) decisive battles/battles that interest me theme, it's proving v popular with the crowd.

I like the suggestions made by others, could be some good reading. If I can make my suggestions - the English War of the Roses. Big, voilent battles, decisive for the nobles involved, but for the rest of country, did it make any difference at all?

DF: I'd argue that the only one that did, in the end, was Bosworth, in that it put an end to the Plantagenets and brought in the Tudors and more than time it was, too, since Henry II's brood and their descendents really were a right fucking mess, many of them. Not that the Tudors were saints, but after the chaos of the Angevins and then the bloody York-Lancaster feud, well...

And I should note that even after 1485 the Yorkists wouldn't lie down. Henry VII had to do a good bit of fighting and executing before the Tudors could safely ignore the pesky bastards. Even his son had to deal with some continuing unrest.

I'd agree with you re Bosworth. The most interesting period for me is after Henry Bolingbroke deposes Richard II. Despite having pretty good personal reasons to depose Richard, and in overthrowing a tyrannical ruler being backed by a lot of popular support, he meets opposition in the form of assassination attempts, rebellions & invasions from the outset of his succession, many of them following one after another. I'm sure there are lessons in crisis management & strategy there. Though it didn't stop him being eventually usurped by his son Henry V.

Chief,

You've out done yourself with this article.

Do you know why the Crows Nest marker appears to be defaced-the first line looks chiseled off of it.

jim

DF: I've always thought that the fourth through the sixth Henries were something of a mess. Bad as R2 was it might have been better for England if he'd been left alone.

jim: It looks as though someone chiseled out a line that claimed that the OP was named by the scouts that morning "because there was a crow's nest there"; I'm guessing that either a local or a history buff had better information or just disagreed with the statement and rubbed it out.

---------

BTW, folks; I wanted to note that this article is the first of a two-part essay on LBH, the second being jim's thoughts on the events of June, 1876. I sent him the original post very late and he's working on his material now, but I hope to have it up here soon and am convinced that he'll give us much more to think about.

Chief,

I'm in the barrel now.

Today i'll do a dual comment-one cmt on your exhaustive art, and one ATTEMPTING to equate this battle to the PWOT.

Pls bear in mind that this will be simply comment and a footnote to your work. A work that is beyond my ability to equal.

But i'm on the scent now.

jim

btw - my word verification this morn is INGINS.Is that funny or what?!

jim

My only dispute, and its a minor one, would be your last point as to whether the Plains tribes' lack of nationhood made much of a difference. The Iroquois Confederacy provides one example of Native American tribes working together under a larger framework, so it wasn't totally unknown for some NA to operate this way, yet in the end it made little difference against the overwhelming forces of demographics and technology the natives were facing.

Even if the Plains tribes could have formed something like the Confederacy - which is a big "if" considering their nomadic lifestyle and the distances involved - I can't conceive that it would have made that much of a dent in the western expansion. Even ten Little Big Horns would have at best imposed a temporary delay on what was to come.

tagryn: Point well taken, and I should revise that statement. The combination of epidemic disease and agriculture surely doomed the tribes, even if they had managed of form some sort of continent-spanning confederation. Their only hope might have been to have adopted the white's methods AND hoped for a caesura in the western expansion, and the latter almost certainly wouldn't have happened, even if the natives had managed a sort of Meiji Restoration-level industrialization all on their own.

Chief and tag,

There's some speculation that the nomad tribes were less stricken by imported diseases b/c they had less exposure and were more remote. The larger Mississpi river cities actually disappeared after exposure.

Some theorize that the survivors actually become the nomadic tribes.

The eastern tribes also interbred more readily than the western tribes. As a result their leaders often had a foot in both camps, ergo they understood the whites.This often affected their leadership and treaties.

Whether east or west all the NA's got the tube steak.

jim

Chief,

Just a little trip down the backstreets of history.

While doing a little research on Spensers/Burnsides and Buford at Gettysburg a little fact popped up.

Myles Keogh was an aide to Buford and was a faithful officer and well breveted thru out the CW.

He was used to desperate defensive as well as offensive fights. His element was destroyed at LBH, but they had appropriate leadership at his level.

Just a little fact that bears on your historical section.

I found this AFTER i did my cmts which haven't been printed yet.

jim

A great read. Someday when I retire I'm going to come back and read the whole series.

I remember a Twilight Zone episode about a tank crew who find themselves transported back in time and place to LBH. They leave their vehicle, grab their rifles and hoof it to help Custer out.

I live less than a half-day's drive from Commanche, Keogh's horse.

The link:

http://www.garryowen.com/comanche2.htm

bb

jim: The Keogh bio makes me a little more confident that his wing was maneuvering in open order when they were overrun. A smart, experienced ACW officer would certainly know how to organize a dismounted defense and given the disparity in firepower should have been able to sicken the Sioux and Cheyenne enough to last longer than an hour, at least.

I think that his last thought was probably something like "What the...fuck THIS...!" as the dog soldiers came boiling up out of the ravines and took down his L Company skirmish line while half of C Company bolted for it.

The other thing that bears on this is that in open order - that is, maneuvering offensively - even a leader like Keogh can only influence the nearest couple of guys around him. But in a defense a good officer can do a lot more to keep the guys' heads' up and firing.

Chief,

From the pics and the topo of the battlefield istm that Keogh would have organized on the military crest , if he had the ability or luxery to do so.

As he set his defense the Indians could sweep down hill on him, which is always a bad thing.

As a soldier i think his element was running and fighting until they realized that they were decisively engaged, at which time they went to ground and sold out as dearly as they could.

Myles was a fine officer.

jim

A fine analysis, Chief. I myself though am of the 'Custer-was-an-idiot' school.

I did have the opportunity last summer to stop at the LBH Battlefield. We were travelling to the east coast to see in-laws and just happened to see the sign off of Interstate 90. Wasn't going to stop because as I said above Custer was never my hero. But we needed gas and coffee so stopped. Glad we did. Standing on the actual terrain brings a lot to the picture.