Dates: 14 JUL-12 SEP 1683

Forces Engaged: Holy Roman Empire and AlliesThe military forces available to the Holy Roman imperium in and around Vienna changed significantly in September.

Vienna Garrison (14 JUL - 12 SEP 1683)

From the beginning of the siege up to the end of the first week of September the only Imperial force engaged was the Vienna garrison and the volunteer militia raised from the city's male population. The regular garrison troops are reported to have comprised almost a third of the Imperial regulars then available in the central European Hapsburg lands, 11,000 of the some 30,000-odd troops reported operating in the Vienna area.

The secondary sources I encountered did very poorly breaking this total down into unit strengths, which is remiss of the authors, since the units and authorized strengths are set out plainly in Knolles and others (1687) as follows:

Infantry* Regiment Staremberg (COL Maurice of Ketlin, commanding) 2,000 all ranks

Detachment of Infantry Regiment Keiserstin (LTC Wolfargschenek) 1,000 all ranks (probably 5 or 6 companies)

Infantry Regiment Mansfeld (COL Lesly) 2,000 all ranks

Infantry Regiment Souches (COL Lewis of Soulches) 2,000 all ranks

Infantry Regiment Schaffemberg (commander not listed) 2,000 all ranks

Infantry Regiment Bercks (commander not listed) 2,000 all ranks

Detachment of Infantry Regiment Newbourg (7 companies, commander not listed) 1,200 all ranks

Detachment of Infantry Regiment Heister (COL Baron Heister) 1,000 all ranks (as Keiserstein)

Detachment of Infantry Regiment Dimik (5 companies, commander not listed) 600 all ranks

Vienna Garrison (3 companies) 1,200 all ranks

(*Note: You probably don't remember this, since it was almost ten years ago and in a post about a very minor engagement in a rather forgotten war, but we've talked about the state of the infantry in the late 17th Century. I think I did a good job then, so I'll simply copy and paste that here:So an authorized strength of the garrison was about 15,000 infantrymen; however, the assigned strengths of these units were considerably lower by July of 1683.

"Although dimly remembered now if at all, the late 16th to mid 17th Centuries were the heyday of the "pike-and-shot" period.

The invention of hand-held gunpowder projectile weapons goes well back to late medieval times. The arquebus, really just a sort of improved hand-cannon with a matchlock, was being used in maneuver warfare by the early 1400s. Like most other early gunpowder weapons, the matchlock arquebus was less accurate than a longbow and didn't hit as hard at a distance as a crossbow, but had a faster rate of fire than the most powerful crossbow, was easier to learn to shoot than a longbow, and was more powerful at close range than either.

This matchlock weapon had a whole laundry list of drawbacks, though. It was inaccurate, noisy, prone to misfires in the damp or wind (which might blow the match out!). It generated dense clouds of smoke and between that and the noise blinded and deafened the firerer, making command and control a nightmare for pike-and-shot unit officers. But the worst part was that it was hellaciously slow to reload. Slow, slow, slow. And the trick to fitting a blade on a musket was waiting for the 1670's when first the plug bayonet and, nearly immediately afterwards the socket bayonet of the 1690s, gave the musketeer a way to defend himself while reloading.

(It's worth noting that most of the troop units involved in this engagement seem to have been pike-and-shot types. The plug bayonet had so many drawbacks that many European armies stayed with the pike until the socket bayonet became widespread. For the defenders of Vienna the fear of being overrun by cavalry whilst reloading wasn't an issue, so my guess is that the pikes were left in the racks and it was musketry until handstrokes and then sword and musket butt.)

Musket fighting in the late 17th Century was in that tricky stage where the technology was mature enough that nobody really wanted to go back to the bow. But there were still a lot of bugs in the business, and the musket-firing infantryman was not yet the lord of the battlefield he would become twenty years later. He still needed help to stay alive. He found it in a very old military technology; the pike.

Beginning with the Spanish tercios of the 16th Century the footsoldier in Europe reorganized around a central block of pike-armed infantry (who typically retained some of the armor of their medieval predecessors; a helmet, breastplate or breast-and-back and tassets over a "buffcoat" of thick leather. This central pike phalanx could act as a moving redoubt for the musketeers to hide in or behind when cavalry threatened, or could roll over lightly-armed infantry and engage similar pike formations in "push-of-pike" melees that the musketeers lacked the brute force to win. Typically the ratio of pikemen to musketeers in the 1680s was about 2 to 1, musket to pike, well up from the 1-1 of the early tercios but far from the all-musket-armed foot regiments of 1700.

So the European infantry units that charged down the Kahlenberg were a strange mess, caught in amber between now and then; part medieval pikeman, part modern bullet-firing infantryman.)"

The difference between the technical and tactical situation at Auldearn in 1645 and Vienna in 1683 is that the two English combatants had evolved together. The European armies and the Ottoman army had not, and we'll talk about that when we get to the Turkish forces.

Dupignis Regiment of Horse** 600 all ranks

(**Note: Just like the infantry, the horse soldiers of the 17th Century were responding to the Gunpowder Revolution.So, at least on paper, 15,000 infantry, 600 cavalry, and 317 cannon of various calibers ranging from fieldpieces to fortress artillery.

The glory days of the armored horsemen had ended on the pikes of the Renaissance infantry squares, and had been buried under the cartridge boxes of the massed gunfire of the musketeers of the early years of the 1600s, but armies still needed a force of heavily armed mounted soldiers to smash through lines of shaken or disordered infantry. And they needed even faster-moving lightly armed horsemen to scout ahead of the main force and to fight off the opposing army's lighthorsemen.

Eventually the cavalry troopers evolved into the light cavalry - hussars, light dragoons, and lancers - and the heavy cavalry - heavy dragoons, carabaniers, and cuirassiers - of the 18th Century. The former were screens and scouts skirmishing with carbines, the latter shock cavalry used to shatter and rout formed troops charging home with sword in hand.

At the time of Vienna the light cavalry and the heavy cavalry - usually called "horse" except in Poland (as we'll talk about in a moment) - were there. "Horse", like the Dupignis Regiment, were what would by the 1750s be called "cuirassiers"; heavy men on heavy horses wearing armored vests (or, at least, an armored chest plate) and stout helmets, typically armed with a heavy, straight sword, and a brace of pistols. The lights were called variously "hussars" or "Tartars" (for the Ottomans) and were little changed from the steppe nomads of Mongol years.

The horse pistols themselves were a bit of an anachronism, by the way, a remainder of the "caracole" of the 16th Century, and were unlikely to be used other than as an emergency measure in combat.

The oddity amongst the 17th Century cavalry were the dragoons, who were still evolving. By the mid-18th Century most, and by the beginning of the 19th Century all, dragoons had become standard-issue heavy cavalry trained to charge home. But in the 17th Century they retained some of their original mounted infantry character; enough that the idea of matching dragoons against heavy horse in a stand-up mounted fight was considered recklessly impractical. Dragoons were never counted as "cavalry", always as a separate column; infantry, cavalry, dragoons.

The Dupignis Regiment would likely have been dismounted other than for the occasional sortie, their hayburners useless in defending the walls of Vienna, their heavy armor left in the stables as the troopers were thrown into the desperate fighting in the breaches.)

But...Knolles and others (1687) notes that

"These Regiments when full amounted in all unto 15600 Men; but so many of them had been Killed and wasted with Sickness, that scarce Ten thousand of them enter'd into Vienna; to which being added the Trained-Bands of the City, consisting of 2717, the whole Garrison might be well computed with Volontiers, and Officers at near 13000 Men."So approximately 13,000 all ranks and arms with some 300 cannon ranging presumably from light fieldpieces to heavy fortress artillery under GEN Count Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg.

Imperial/Christian Coalition Field Army (12 SEP 1683)

Knolles and others (1687) breaks down the Christian Coalition forces as follows:

Imperial: (GEN Duke Sachsen-Lauenburg)

Heavy Cavalry - 12 Regiments, 8,200 all ranks (so approximately 680 troopers per regiment, or 68 per squadron assuming a ten-squadron regiment)

Medium Cavalry (Dragoons) - 40 companies, 2,400 all ranks (sounds about right, 60 troopers per company; probably 4 regiments)

Infantry - 42 companies, 6400 all ranks (assuming a ten-company regiment, then about 150 grunts per company...but the odd number of companies and the total troops suggests that either the regiments were badly understrength or the full regiments weren't present. I suspect the former; it wouldn't make sense for the imperial commander to throw together odds and sods from the tag-ends of different regiments.

Bavarian and Franconian: (GEN Kurfürst Maximilian II Emanuel)

Bavarian (GEN Baron de Gonfeld):

Heavy Cavalry - 3,000 (organization not listed; 4-5 regiments of about 600? Millar (2008) states 19 squadrons, which would mean that either the squadron strength was more than double the Imperials or someone's numbers are wrong)

Infantry - 2,000 (organization not listed, but presumably one large regiment or two understrength regiments)

Franconian (GEN the Prince of Waldeck)

Heavy Cavalry - 2,500 (organization not listed - Millar (2008) says 7 squadrons, which is a gross underestimate if the Knolles and others (1687) number is correct)

Infantry - 6,500 (again this disagrees with Millar (2008), who reports only 6 battalions, which would be closer to 3,000)

Saxon: (GEN Kurfürst John George III):

Heavy and Medium Cavalry - 2,000 (presumably about 3-4 regiments)

Infantry - 7,000 (2-4 regiments; presumably 3 two-battalion regiments which would square with Millar (2008) listing the Saxon infantry as 6 battalions)

Croats and Polish: (GEN Lubomiski)

Croats (troop type not listed) 600

Polish (troop type not listed) 2,400

Polish: (GEN Jablonowski)

Heavy Cavalry - 12,000 (listed in Millar (2008) as a total of 6 brigades, 3 of hussars*** and 3 of heavy cavalry, so approximately 2,000 troopers per brigade, or roughly three to four regiments per brigade, which sounds about right.)

Infantry - 2,000 (presumably, again, about 1 large or two understrength regiments)

(***Note: The "hussars" of 17th Century Poland were a sort of bizarre maximal vertex in the military function "hussar". Originating as light irregular cavalry used primarily for scouting and raiding - not surprisingly often considered the same thing by the hussars themselves - in late medieval Hungary these light cavalrymen were originally imported to Poland as mercenaries in the 15th Century.So per Knolles and others (1687) a total of approximately 30,000 cavalry of all types, 20,500 infantry, and some quantity of field artillery that is not described in detail. Most sources state that the Poles brought 28 field cannon, and the Germans/Imperials about 100-110, so about 130-140 fieldpieces probably varying from 3- and 4-pound light guns to 12-pound medium field artillery.

Over the next 200 years the Polish developed a heavy armored lance cavalry they called a husaria, "hussar". These characters owed nothing to the original hussars but were much more like a sort of evolutionary step between the plate-armored chivalric knight of the high Middle Ages and the light-horse lancer of the Napoleonic period. Lighter than the knight, the Polish hussar still wore a cuirass, shoulder and upper arm protection, and a variation of the "lobster-tail pot" helmet of the English Civil War cavalry. They were trained to charge home with lance couched and then lay about with sword and pistol.

The late 17th and early 18th Centuries were the heyday of the Polish hussar; he didn't have to evolve as quickly as his German, French, or Austrian counterparts because his primary orientation was eastwards against troops like the Ottoman sipahi and the Crimean Tatar who were also closer to the Middle Ages than the cavalry of the Enlightenment era. By the mid-1700s, though, faced with flintlock-firing infantry he had dropped the useless heavy armor and had become, again, a light cavalry scout known as a uhlan. The flintlock killed the "golden age" of the husaria as surely as it did the janissaries, as we'll talk about in a bit.

The problem with this is that the 50,000-troop total is significantly lower than typically cited for the Coalition field force, often given as 70,000 to as much as 90,000.

Millar (2008) doesn't even hazard a guess, simply listing the contingents by number of companies, battalions, or regiments.

Wheatcroft (2008) throws out some rough numbers; 40,000 Imperials, 11,000 Bavarians (5 infantry regiments), 9,000 Saxons (Wheatcroft (2008) breaks this contingent down into 7,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry, which leads me to suspect that his numbers are taken from Knolles and others (1687), or the source used in Knolles), 8,000 Franconians (again, similar to the Knolles and others (1687) numbers), and 13,000 Poles for a total of about 80,000 all arms.

My guess is that the Coalition wouldn't have cocked a snook at the Ottoman besieging forces if they hadn't had at least something close to parity in numbers, and although the Ottoman numbers are even less reliable than the Christian the general consensus seems to be that the Porte had close to 60-80,000 all arms in the vicinity of Vienna on 12 SEP.

So my guess is that the field force was probably close to the 80,000 troops cited by Wheatcroft (2008), heavily weighted in favor of (probably close to 3/5ths, or about 50,000) cavalry, 15-25,000 infantry, roughly 140 cannon, under the command of John III Sobieski, by the grace of God King of Poland, Grand Duke of Lithuania, Ruthenia, Prussia, Masovia, Samogitia, Livonia, Smolensk, Kiev, Volhynia, Podlasie, Severia, and Chernihiv, etc.

Ottoman Empire

- If the numbers of the Christian Coalition are difficult to pin down the Ottoman forces are almost impossible.

We have two problems. The first, and most significant, is that the Ottoman historians and record keepers were more interested in the poetry of the event than ticking off the number of grunts digging trenches, and that a hell of a lot of the Ottoman records have been lost. We have the same problem here that we did with the fight outside the walls of Constantinople; the Ottoman sources are just really, really poor.

The Imperials and Western Christian sources, on the other hand, had no reason to try and accurately detail the numbers against them. The Turk being as numberless as the waves on the ocean just made the victory more sweet, right? So why bother trying to figure out how many of the heathern devils there were. "Lots" sufficed to make the win all the better.

"The Forces of Mesopotamia all on Horseback.

Numb. 13000

Those of Assyria and Babilon, as far as Bal∣sora,

14000

Other Asiatick Troops, comprehending the Provinces

Of Sias, Amasia, Maras, Bussia, &c.

30000

The Militia of Iudea, Egypt, &c.

18000

The Militia of Caramania,

8000

Turks out of the parts of Greece,

16000

The Militia of Armenia, Capadocia, &c.

24000

The remaining Asiatick Troops were from Georgia, and the conquered Countries thereabouts, all which were the Forces out of Asia, and Horse,

28000

After these marched the Janisaries of Europe,

12000

Next followed the Tartars, ill Armed and worse Clothed,

14000

Last of all marched the most flourishing part of the Turkish Army, consisting of the Sons and Servants of Pashas; also of the richest Spahees, and other young Men, all richly cloathed and armed,

35000

Pioniers and others with Shovels, Spades, &c.

12000

Gunners, and other Attendants on the Train of Artillery,

13000

Attendants on the Waggons of Ammunition and Provision,

14000

Other Attendants on the Tents and Baggage,

13000

All which formidable Forces amounted unto,

264000

According to a Calculation made by several Italian Writers; but as to my own Opinion, I cannot believe that Asia could furnish half those numbers, and therefore do rather follow the Computation of the Asiaticks, according to this Account:

Mustapha Pasha, Grand Vizier; 15000

Emir Pasha of Adana, 500

Husaein Basha of Bolu, 330

Kara Mahomet Pasha of Diarbeker, 1500

Mustapha Pasha of Silistria, 1080

Halil Pasha of Sivas, 530

Ahmet Pasha of Maras, 710

Husaein Pasha of Aleppo, 950

Osman Pasha a Sangiac under him, 510

Husaein Pasha of Damascus, 2300

Hassan Pasha of Armit, 500

Bei of Gran Cairo, 3000

Basha of Tokai on the Borders of Persia, 340

Bekir Pasha, 500

This Computation may very well agree with the Forces of the first Year's Expedition out of Asia; to which being adjoyned the several Chambers of Janisaries, with all the European Forces both Horse and Foot, as also the Tartars, Transilvanians, Moldavians and Valachians, with the Hungarian Rebels; we may without Romance account the Ottoman Force to consist of a Hundred eighty Thousand (180,000) effective fighting Men, besides Miners, Pioniers, Sutlers, Gunners, Attendants on the Train of Artillery, Attendants and Servants belonging to the Tents, with a vast number of Rascals, and Rabble following the Camp, which may very well be Calculated to amount unto at least 40 000 more.

For the Turks above any Nation in the World have their Camp pestered with the Incumbrances of Baggage; so that if we consider this vast number of 220,000 Men, it will not seem incredible what we find reported, that they spread the Country eight Leagues in length."

The problem is that neither of Knolles and others (1687) numbers are remotely credible. Most of the publications I can find that cover the Ottoman armies of the 17th Century suggest that somewhere between 100,000 and 150,000 was the largest force the Porte could field and support for any time for any distance from the Anatolian and Balkan heartlands.

One thing that hadn't changed since we last met our friends the Ottomans was the overall organization of the Turkish armed forces. The reforms of Mehmet II were still in place, albeit with some tweaks and amendations, in the late 17th Century.

The قپوقولو اوجاغی, Kapıkulu Ocağı, were the hardcore of the Ottoman armies. These "Slaves of the Gate" were the equivalent of the British Household Troops, or Napoleon's Guard organization, and included the يڭيچرى (yeñiçeri) Corps of Janissaries, with an authorized strength about 40,000 to 50,000 sword-and-musket infantrymen in 1683, the household cavalry, Altı Bölük Halkı or Kapıkulu Süvarileri, which included four major elements or brigades:

Sipāhiyān (سپاهيان, roughly, "Armymen")

Silah-dārān (from a Persian term meaning "weaponbearers")

Ulufeciyān (meaning, roughly "retainers"; organized into two regiments, "Left" and "Right" subunits)

Garibān (from a Turkish word for "strangers", also subdivided into two left and right wings or regiments)

I don't have good numbers for this heavy cavalry organization. Given the usual division of infantry and cavalry in a 17th Century army my guess would be that the nominal strength of the Süvarileri probably ran around 20,000-25,000, so roughly 5,000 all ranks per brigade.

And the third major element of the Ottoman Household Division included the gunners, artillery train, and sappers and miners: the artillerymen of the Topçu Ocağı (probably about 4,000 redlegs in 1683), the Cebeci Ocağı (armorers, probably about another 4-5,000), the artillery train Arabacıları Ocağı (the Ottomans, in common with many of the European powers, considered the job of limbering, transporting, and unlimbering the fieldpieces a separate business from fighting the guns, and thus separated the wagoners who drove the gun teams from the gun crew itself. The records suggest that the Porte employed about 400-500 of what would come to be called "artillery train" troops by the 19th Century).

The Household Artillery included a specialized group of gunners and guncrew for heavy mortars, the Humbaracı Ocağı.

One thing to note is that every historian comments on the paucity of Ottoman artillery. A campaign that was expected to culminate in the taking of a fortified city would require massed artillery, and the gunfire of heavy siege cannon, at that. But we'll talk about that when we get to the siege itself.

The final component of the Ottoman Household included the engineers, including what would come to be divided into sappers for engineering above the ground and miners, Lağımcı Ocağı, for work below. I would guess that the engineering troops would have not exceeded the numbers of the artillerymen, so probably no more than 4,000; as in most armies, these specialists would have directed the work - the hard digging would have been done by the grunts.

The bulk of the Ottoman force before Vienna would have been, as it always had been, composed of a combination of feudal levies and conscripts.

The largest single element in this group would have been the toprakli, feudal or fief-holding retainers of the sultan. This element largely provided suvarisi heavy cavalry from the large Ottoman holdings in Anatolia and Rumelia. The toprakli weren't regulars, like the kapikulu units, but they were well led and well organized, fully fit to stand in the line of battle alongside the Household outfits.

The serhadkulu were drawn from the frontier provinces and included light, medium, and heavy cavalry as well as pioneer, garrison, and light infantry. By this point we're talking irregulars, not line troops, but the serhadkulu were still typically better armed, led, and organized than the real wild men from the outlands. Yerlikulu troops included levied fusilier infantry and artillerymen for the border forts. The seymen peasant militia that would have been conscripted for the campaign wouldn't have typically provided much military value. But in a siege there's always a lot of pick-and-shovel work, and a husky Anatolian farmer's kid can dig as well or better than a veteran infantryman.

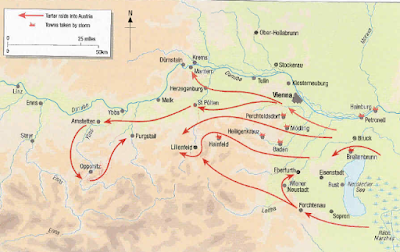

The army of Mehmet led to Constantinople included a mass of frontier wildmen, the başıbozuk. By the 17th Century most of the Anatolian wilds had been pretty tamed, so in the place of these irregulars the Ottoman force brought in about 40,000 light cavalry from the Khanate of Crimea. These "Crimean Taters" (or "Tartars") would have been the reconnaissance and security element of the Ottoman force, fanning out ahead of the siege train and the heavy force alongside it.

Given the usual rear detachments and units diverted to non-combat assignments my guess would be that Kara Mustapha probably had about 15,000 janissary infantry, 10-12,000 Süvarileri cavalry, probably 2,000-3,000 combined artillerymen, artificers, and train, and another 2,000 or so engineers, so a total of about 30,000 in the Household Division before Vienna.

Assuming some 40,000 Crimean Taters started out the campaign my guess is that there would probably have been some 20-30,000 left by July, so about 30,000 light bow-and-sword armed cavalry.

The balance of the Ottoman force would have included some sort of mix of provincial infantry and cavalry, probably about the same number or a little more than the Household troops. Let's say 30,000 infantry, 20,000 cavalry for a total of about 50,000 provincials, everything from suvarisi lance-and-sword heavy horse to yerlikulu fusil-musket-armed skirmish infantrymen.

The real problem for the besiegers comes here; only about 150 cannon artillery, and according to most historians many of these guns were light (meaning 6- to 12-pound guns or the equivalent) fieldpieces. Supposedly only about 30 of the Ottoman guns ran to 24-pound weight or above; true siege guns. We've only gotten to the order of battle portion of this piece and already come across one sign of real trouble for the Ottomans. The Vienna Field Force set out on a campaign whose objective was the taking of a fortified city without a real battering train.

So approximately 100,000 to 150,00 all arms at the beginning of the siege (possibly as few as 80,000 to 90,000 by the field engagement on 12 SEP), about 150 cannon, under مرزيفونلى قره مصطفى پاشا, Merzifonlı Ḳara Muṣṭafā Paşa, Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha, سرعسكر, Serasker and Grand Vizier of the Sultan محمد رابع Meḥmed-i rābi', Mehmet IV, also known as "Mehmet the Hunter".

The Sources: The events of 1683 were well within the literate era of western Europe, so printed accounts of the events, including war diaries and personal accounts along with the "official" versions prepared by the Hapsburg monarchy would have started circulating almost before sunset on 12 SEP.

Numerous primary accounts of the siege and the engagement on 12 SEP were printed within as little as days and certainly within weeks of mid-September, 1683. This scholarly inquiry into the dissemination of the events notes that

"...before the end of September, news and accounts of the siege, of its celebrations, poems etc., were already published and copied, in all the main European editing centers. Most of these ephemeral texts have disappeared today. Nevertheless I have until now identified around 300 titles immediately printed after the victory. Some are very detailed. For instance, the detailed diary of the imperial army servant Vaelckeren, originally written in Latin, was translated in French, Italian, German, and English. Or the officer Hoffman’s diary, the accounts of the diplomats and at the same time hostages who witnessed the events on the Ottoman side (Benaglia’s, secretary of the emperor’s ambassador the count of Caprara, Count Marili’s, or the Ottoman chronicle by Evliya Celebi)(d'Albis, 2017)I do want to note that I cannot find evidence that Çelebi, who died in 1684, was involved in the 1683 campaign. His Seyahâtnâme or "Book of Travels" is described as "...mixing fact and fantasy; he described places he could not possibly have visited", so I have some doubt about the historical acuity of the author of the linked document.

But of her broader point I have little question. The late 17th Century was littered with broadsides, pamphlets, tracts, and accounts of recent events, the newspapers of the period. The victors of the campaign would have wanted to ensure that their success was as widely broadcast as possible.

For example, it seems that Sobieski's letters from the field to his wife were published in that same year.

(The citation I have encountered claims that the letters were first published on October 19, 1683, in something called the "Cologne Gazette", which in German would have been the Kölnische Zeitung. The problem is that I can't find evidence that a news sheet of that name existed in the 17th Century. The citation always seems to lead back to the 1889 Catalog of Printed Books printed under the auspices of the British Museum, but I can't seem to trace it further than that.)Still, I suspect that Sobieski's letters were, indeed, published as part of the Hapsburg/Holy League post-campaign propaganda blitz.

Several eyewitness (or ostensibly eyewitness) accounts exist, such as the Vienna in Turcis Obsessa, in Christianis Eliberata, Sivi Diary Obsidionis Viennensis (usually translated as "A relation or diary of the siege of Vienna") by one Johann Peter Vaelckern, a Viennese attorney. This work was printed in English as early as 1684.

A man named Luigi Marsili (or Marsigli) observed the siege from the Ottoman camp, having been captured by Tatar raiders early in the campaign. His "Report on the Siege of Vienna" appears to be a late 17th or early 18th Century account of his view of the events of the Vienna campaign. All the references I can find refer to a 1930 edition which is obviously a reprint. I cannot find when his account was published, but my guess is no later than the 1690s - public interest would have waned much after that,

On the other side of the hill, however, we have the same problem we had in 1453; the Ottoman records are sparse, and what there is appears to be predominantly provided by Europeans traveling in Ottoman lands or with the Ottoman forces. It is instructive that Wheatcroft (2008) cites a total of 59 contemporary printed or manuscript sources; not a single one is written in Turkish or has been translated from that language.

I suspect this is because the Ottomans lost, and like most empires the Ottomans didn't like to talk about their losses. I suspect that another factor is that any chronicler or historian traveling with the Ottoman forces would have been a client of Mustafa Pasha and, as such, unemployed within weeks of the defeat and unlikely to be particularly arsed to recount how he had lost his paycheck. I also suspect that the same problem we encountered in 1453 had not much changed in 1683, the quality of the works Philippides and Hanak (2011) brutally dismissed as "...meager narratives, with such an overwhelming poetic imagery that they become difficult, if not impossible, for the historian seeking facts about the siege."

The secondary sources are so numerous that the only problem is settling on which to use.

One of the secondary sources I used to prepare this post is a 1687 work entitled The Turkish history from the original of that nation, to the growth of the Ottoman empire with the lives and conquests of their princes and emperours, originally published in 1603 by Richard Knolles.

The work was reprinted numerous times and was expanded in the late 17th Century by Sir Paul Rycaut to include the major events in the Ottoman Empire up to that date. It is rather difficult for a 21st Century reader, as the text is printed with many of the conventions of the 17th Century that a modern reader finds fussy and ornate, but the information appears generally sound and similar to other contemporary accounts.

My main secondary source for this post was Andrew Wheatcroft's 2008 The Enemy at the Gate. This work is interested primarily at putting the Ottoman-Hapsburg clash in the framework of modern European-Turkish (and, from there, the larger Muslim world) relations. It's a serviceable work and a fun and easy read, although my issue with Wheatcroft (2008) is that he is extremely unfamiliar with the Ottoman accounts of the campaign or Ottoman sources in general. He also makes some simple errors that he should have corrected such as the spelling of participants' names.

John Stoye's 2008 The Siege of Vienna covers much the same ground, and covers it very well.

I found a good little monograph that discusses the Peace of Vasvár (Michels, 2012) here. It is especially good for the detail it brings to the issue of the military stupidity of the Hapsburg Counter-Reformation brutality in pissing off Protestant Imperial subjects in Hungary.

"The main protagonists of the letters - Jan Sobieski and Maria Kazimiera – described themselves as: Beaulieu, Celadon, Autumn, Gunpowder, Orondat and Silvander and as Astrea, Essence, Dawn, Cleopatra, Rose and Countess Soissons. The letters became known as confitures or fruit, love - as oranges, and health – as aroma. The surrounding of both authors (the court and the family) was given amusing and, at times, malicious pseudonyms. Such harsh treatment was applied especially in the case of Jan Zamoyski (described as Dossier, Fountain, Fool, Horse, Mackerel), his haughty sister, Gryzelda Wiśniowiecka (Double Bass, Baking Tin) and even their servants (Thorns, Ropes). Seabirds signified the parents of Maria Kazimiera, Playing Ground was the Warsaw court, and Enchanted Palace was Versailles and Paris. Unfortunately, many pseudonyms remained un-deciphered and we shall probably never find out the identity of: Sponge, Apple, Knee, Crocodile, Potty, Slipper or Hunting Hounds." (Widacka, 2017)Sounds like the Sobieski house was a fun place.

The Campaign: The 1683 campaign was just a part of the long, long war between the European, Christian powers and the Ottomans that had begun not long after the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 that had put the Europeans in the front line between Europe (a welter of fractious western, Christian-but-violently-divided between Catholicism and Protestantism states undergoing the social, economic, and technological upheavals of the Renaissance and, later, the Enlightenment) and Ottoman Eurasia (a centralized Muslim empire dominated by the authority of the Porte).

Perhaps the hardest question to answer is; Why bother? Why this campaign, at this time, with this objective?

It's not like the Ottomans didn't have enough else to do. The eastern edges of the empire were always at risk from Persian or Central Asian incursions, and the rising power of Russia was a threat from the north. The Italian city-states of Venice and Genoa were a menace to the Anatolian littoral and the Adriatic and Pelloponnesian coasts. And certainly the turbulent peoples of the Balkan mountains were no prize, other than perhaps as soldiers and the Turkish heartland produced more than enough of them.

So the real answer is "Because". Because the Ottomans were a restless people, their rulers had always been bent on conquest, their religion, like Christianity, called upon them to bring the infidel inside the umma, out of the "House of War".

Because the Ottoman Empire, like many other empires, was like a shark; it needed to keep feeding itself on conquest or die.

1453-1526 - Ottomans versus Hungarians

The first Ottoman incursions past the Golden Horn and into Europe had come in the 14th Century, but it was by the mid-15th that the great power of southeastern Europe, the Kingdom of Hungary, was meeting the Ottoman armies.

These Ottoman-Hungarian Wars ran back-and-forth across southeastern Europe and the Balkans for seventy-odd years until the Hungarian power was crushed at the Battle of Mohács in 1526. The kingdom was partitioned, with the Ottoman empire absorbing the southern and eastern pieces and the Hapsburg-ruled "Holy Roman Empire the northwestern province of "Imperial Hungary". Technically the eastern province of Transyvania was independent, but in fact it was an Ottoman dependency and was reliably anti-Hapsburg into the late 17th Century.

The end of the Hungarian wars only meant that the new force opposing the Ottoman advance into Europe was the Hapsburg-run outfit that was, famously, neither "holy", nor "Roman", nor and "empire".

The Holy Roman Empire - let's call it the "HRE" to save bandwidth - imperial idea wasn't necessarily a bad one. Europe's single biggest source of troubles from the fall of Rome to the formation of the European Union has been warring states, with internal wars, rebellions, and civil wars a strong second. The notion of a strong centralized authority capable of keeping the peace and settling disputes wasn't a bad one. The problem was, of course, that everyone in Europe thought that their king, prince, duke, count, or tax accountant should be the one in charge.

So for much of it's existence the HRE existed more in name or as an idea than as an actual empire. At any given time one of more of its component states was thinking about rebellion, or in rebellion, or leading a rebellion against the Holy Roman Emperor. If not that, then the French kings were at its throat, seeing the HRE as the biggest threat to French expansion.

Perhaps the single most awful period in the thousand-odd-year history of the HRE came about because of the great Christian schism of the 16th Century. Protestant-Catholic conflict, culminating in the The Thirty Years' War between 1618 and 1648, gutted the central German states within the empire. Worse, it made relations between the Catholic Hapsburg emperor and his Protestant subjects somewhere "tense" and "murderously hostile".

This affects our story because many of the people living in the various pieces of what had been Hungary were some form of Protestant.

And after the Hungarians went under the Austrian (and Croatian, Bohemian, and "Imperial Hungarian") domains of the Hapsburg Holy Roman Emperors were the front line against the Terrible Turk.

1526-1606 - Ottomans versus Hapsburgs (and Venetians, Holy Leagues, and Knights of Malta, among others...)

The people in the Hapsburg dominions of southeastern Europe, and those in the Ottoman ones, fought, made deals, fought, made treaties, fought, and pretended not to fight while busily raiding and torching each others' borderlands for the next 150-odd years. They were always enemies. But they weren't always each other's worst enemies.

For one thing, for the Hapsburgs there were always the French.

France in the 16th and 17th Centuries was Germany in the 19th and 20th; always up to some sort of political or military fuckery, and usually when not actually engaged in said fuckery was either recovering from the last bit of fuckery or contemplating the next one.

France hated the fact that there were Hapsburgs in Spain and Hapsburgs in Germany (as part of the HRE). They also wanted pieces of Italy, which those Hapsburgs either had or wanted, or weren't willing to let the French have, either. So as much time as the Imperial troops spent fighting the Ottomans they spent as much or more fighting the French, going all the way back to the year before Mohács, when the Imperial forces whipped King Francis I of France at Pavia.

Which, by the way, was just the start of the Imperial troubles with Frankie Valois. As I wrote back in 2009:

"You would think that Pavia should have been hell and fucking disaster for France. The King in chains. The nobility decimated: Montmorency and Flourance captured; Bonnivet, Le Tremoille, La Palice, Suffolk, and Lorraine dead. The French army butchered, all of northern Italy prostrate before the Imperialists.So it wasn't like the HRE could really concentrate on Radical Ottoman Terrorism. Every time they thought about it some Frenchman was poking them in the giggy.

You’d think that.

But then you read that a mere eleven years later Francis was BACK, capturing Turin and making a general nuisance of himself in north Italy. Again.

And six years after THAT…this time, he’s allied himself with the fucking Ottoman Sultan Suleiman, capturing Nice, fighting the English and Imperials in the Low Countries.

Francis finally quits messing around in Italy in 1547. Only because the pigheaded persistent bastard finally fucking dies.

Really. Some people..."

But, Frenchmen be damned, the Imperials and the Ottomans did manage to get stuck into each other quite a bit.

In 1529 there was the First Siege of Vienna; the Ottoman army was at the end of its' logistical tether, though, the siege guns were sunk in some Hungarian swamp, the weather was turning, and finally Suleiman the Magnificent decided to call it a night and the Ottomans sloped off back into their part of Hungary.

That was the beginning.

Over the next 140-some years the Ottomans and Imperials fought over the borderlands where Hungary met Austria (as well as Croatia to the southwest and Poland to the northeast).

This wasn't constant; some of the time the Austrians needed to attend to the damn French, and some of the time - though not always at the same time - the Ottomans were busy with their own local rivals, the Safavid Persians of Iran. But even when the powers weren't officially at war, their proxies, and the rough men of the borderlands, kept up the constant bleeding of raid and counter-raid.

Of course, those who suffered weren't the noblemen and statesmen who met in paneled rooms to discuss the passionless choices of high strategy. They were the poor sods who were trying to scratch out a living along the fringe of empires, just as it has always been and always will be.

So the Ottomans (and their proxies) fought the Imperials (and their proxies) in the imperial borderlands over the next twenty odd years until the frontier stabilized. A cease-fire negotiated in the 1550s left the HRE with their little slice of northwestern Hungary and Croatia, the Ottomans with the rest, with the exception (as we noted above) of Transylvania (insert Dracula "bleh! bleh!" noise here)

which was notionally independent but functionally an Ottoman ally.

The cease-fire lasted until the 1590s, when - in quick succession - the Ottoman Vizier Sinan Pasha raised the horsetail standards of war against the Hapsburgs, and a series of rebellions broke out in Ottoman-ruled (or -influenced) Balkan lands, including Serbia, Moldavia, and Transylvania.

The so-called Long War ran from 1592 to 1606 and ended without a decisive result. The Wiki entry does a good job of summarizing the outcome:

"The Long War ended with the Peace of Zsitvatorok on November 11, 1606, with meager territorial gains for the two main empires—the Ottomans won the fortresses of Eger, Esztergom and Kanisza, but gave the region of Vác (which they had occupied since 1541) to Austria. The treaty confirmed the Ottomans' inability to penetrate further into Habsburg territories. It also demonstrated that Transylvania was beyond Habsburg power. Though Emperor Rudolf had failed in his war objectives, he nonetheless won some prestige thanks to this resistance to the Turks and by presenting the war as a victory. For the first time, he was also recognized as an Emperor by the Ottomans. The treaty stabilized conditions on the Habsburg–Ottoman frontier."The cease-fire in Hungary held for over seventy years.

But that didn't mean the Ottomans and the Western powers stopped fighting. The late 15th and 16th Centuries were punctuated with fighting in and around the eastern Mediterranean. The Ottomans took the island of Rhodes in 1522, and tried and failed to take Malta in 1565. The Imperials under Charles V (Holy Roman Emperor, but primarily the leader of the Spanish branch of the Hapsburg family) took Tunis in 1535 and held it for forty years. The Ottomans took Cyprus, right before losing one of the better-known engagements from this long war, Lepanto, in 1571.

The fighting in the Med cooled off after the Venetians sued for peace in 1573, and the Ottoman-Hapsburg struggle settled into a long Cold War between the first decade of the 17th Century and the 1660s.

1663-1676: Proxy Wars and Border Incidents, and the Ottomans vs The Hapsburgs 2 (and the French, and the Germans, and the Hungarians, and sweetjesus let's just talk about what happened...)

The whole nutroll begins with a minor proxy war in 1658. The Ottoman client ruler of Transylvania (bleh! bleh!)

Prince George Rákóczy II decided he wanted a little whatever-the-Transylvanian-word-for-lebensraum-is and decided he wanted a piece of Poland to get it. So he conspired with the Swedes and started the "Second Northern War" (or maybe the "First" Northern War, or, more safely, the "Northern War of 1655"), involving Poles, Lithuanians, Swedes, Transylvanians, Danes, and Leopold I, the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Austria.

The whole thing is an ugly mess, even by the standards of 17th Century Central European wars, but the upshot was that Rákóczy got his ass kicked out of Poland and pissed off his Ottoman bosses, who promptly invaded and took Transylvania (I don't know how to say "bleh! bleh!" in Turkish; probably something like "saçmalamak!") in 1662.

This worried Leopold because the Ottomans didn't stop there. They took the fortress of Nové Zámky, a key to Slovakia and the upper Danube basin. The Ottoman forces, both regulars and Tatar reivers, tore up Slovakia, Moravia, and Silesia in 1663, taking thousands of slaves and generally wrecking the place.

(That's him, by the way, painted some years earlier when he was a broth of a boy, but you can still see the pouty Hapsburg lip that suggested Leopold was not a good guy to cross...)

So Leopold called the Imperial Diet which, despite the name, was not a weight-loss gimmick. The Diet dragged in all the representatives of the various places - principalities, cities, religious houses, you name it - that composed the HRE. Here, to what must have been Leopold's utter horror, devout Catholic and anti-Frenchman that he was, a gang of German Protestant polities and Louis XIV promised to send him soldiers to fight off the Terrible Turk.

And they did.

At the Battle of St. Gotthard in 1664 the Christian coalition caught the Ottoman force in the middle of a river crossing and hammered the hell out of the advance party; what helped was that the Rába had risen overnight, trapping the Ottoman elements on the near side. The Ottoman invasion of Austria was done, so Leopold - who was more worried about the French than the Ottomans - signed a quick and dirty deal with the Porte.

"According to contemporary observers, the Ottomans had essentially cut Royal Hungary into two parts with a military corridor that stretched from Érsekújvar (Neuhäusel, Nowé Zámky)—formerly a crucial Habsburg border frontier castle and now the center of Turkish power in Royal Hungary—all the way to the Moravian border. Not surprisingly, Ottoman troops were operating with impunity in Habsburg Hungary’s interior." (Michels, 2012)That Peace held on for just about twenty years.

Sorta.

The Ottomans, quickly bored of peace and looking for trouble, actually began a new campaign only two years after Vasvár, in the Ukraine. An alliance of border reivers - Cossacks and Tatars - loosely allied with the Porte tried to bite off a piece of central eastern Europe and were knocked around by the Poles under a boy we'll meet again, Jan Sobieski, the "Field Crown Hetman" (in effect, the General of the Armies) of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

This, unfortunately for Poland, brought the Ottoman regulars to Ukraine in 1671.

For the next five years Ottomans and Poles fought over the Ukraine. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was pretty badly mishandled. The main reason seems to be more political than military - the Polish legislature, the Sejm, was a hot mess (a single veto was enough to stop any action, so the Sejm did a whole lot of nothing when it should have been raising money for troops to fight the Ottomans...) and the end result was that the Commonwealth lost a chunk of Ukraine and a bunch of good troops.

Then the borderlands settled in for about seven years of uneasy "peace".

1683 and the Vienna Campaign

Just as we may never know what motivated the Sultan and his Vizier to launch the campaign, we may never know exactly why the Ottoman objective for the 1683 campaign was fixed so firmly on Vienna.

Typically, for a military campaign that is designed around a geographic objective to succeed, that objective also needs to have a military value. In 1683 Vienna was not a particularly vital military post. It was a fortified city, but its fortifications - and we'll discuss this in detail in a bit - weren't particularly strong. As a barrier to movement along the Danube the city's location might have been valuable, but it was also at the far edge of the Ottoman world; if captured it would be an outpost, not a main line of defense. And an outpost that would require a large garrison that would suck up a tremendous logistical effort to sustain and support, and would always be extremely vulnerable to recapture.

Vienna's value seems to have been primarily symbolic, like Moscow in 1812 or 1941, and we know the problems those campaigns encountered.

Wheatcroft (2008) explains another problem with this; the Ottoman officers who knew the region didn't want it:

"The campaign that the Ottoman commanders in Hungary wanted was very limited: capturing one or two of the powerful Hapsburg fortresses north and south of the Danube. Seizing the star-shaped bastions of Győr of the gun emplacements of Komárno which conrolled the river would have altered the strategic balance decisively and left a gaping hole in the Hapsburgs' defensive line. It would have strengthened control over the Turkish-ruled lands west of Buda, and perhaps have allowed for deeper advances into Royal Hungary. Yet the symbolic value of Vienna was plainly more persuasive than military logic."Wheatcroft (2008) suggests that the reasons for the ambitious plan were a combination of the sultan Mehmed's desire for military glory and his Vizier Mustafa's ambition. They could give a shit what their local experts wanted. They wanted glory, and glory was inside the walls of Vienna.

With that in mind, in May the Ottoman forces assembled in their marshaling areas near Belgrade. The usual dog-and-pony shows were held, the troops blessed and exhorted, and the forward elements crossed the Drava River at Osijek on 14 JUN 1683.

The Ottoman main force was preceded by a screen of Tatar light cavalry.

These characters, as we've noted, were hordes right off the steppe, bands of little men on little horses able to ride quickly and tirelessly, and arrive deep in the Christian lands before any warning arrived. They provided intelligence of the enemy movement and denied the Hapsburg commander, Charles of Lorraine, information of the Ottoman dispositions.

Behind the Tatar screen came the Ottoman main body, their march order and logistics still far more sophisticated than their European enemies'.

By 27 JUN the Ottoman field headquarters was at Istolni Belgrade, about 60km southwest of Buda. After a final, notional council of war (stacked with his cronies) Mustapha Pasha order the troops to swing south of the guns of Győr into the wilderness.

This was a fairly brilliant move. The Austrian leadership assumed that any Ottoman advance would have to come along either the north bank of the Danube or the immediate south shore.

The lands well south of the river were considered, when considered at all, a trackless, river-swamp-and-forest waste.

Instead, Lorraine was sent east to Esztergom, an Ottoman fortress north of the Danube above Buda; or, at least, his infantry and cavalry were. The Imperial artillery struggled along the miserable frontier roads getting bogged to the axles. The Imperial force spent most of June and July marching and countermarching along the Danube and perfunctorily besieging Esztergom.

Finally, early in July, the Imperial force pulled back to a position closer to Vienna. The Imperial infantry remained on the north bank of the Danube. Lorraine and a cavalry element crossed to the south bank to try and find the Ottomans.

While the Imps were farkling about Imperial Hungary the Tatars had already been through the south-Danubian wilderness and had reported the small tributary streams of the Danube were remarkably low and were easily fordable or bridgeable and the roads were no worse than anywhere along the river. By early July the Ottoman main body was at the town of Moson on the Austro-Hungarian border and nearly to the Imperial force at Bratislava.

Wheatcroft (2008) describes Bratislava as "...where a line of hills on the southern bank of the (Danube) river matched the hills on the northern side. It was the last position before Vienna (where) an army could make a stand..."

By the time Lorraine and his forces had been alerted to the Ottoman movement "...he (Lorraine) could see a huge reddish cloud of dust rising into the air in the distance. Then, as they (Lorraine and his staff) spoke, he noticed that there were numerous columns of smoke behind him, between the Army and Vienna, indicating that the Turks' advance guard was already between him and the capital." (Wheatcroft, 2008)

Lorraine ordered his infantry west along the north bank, and led his cavalry into the capital from the south. The Emperor - and about some 50,00-60,000 civilians - had rolled, or raced, scrambled, or fled out of the capital that same day, 7 JUL.

On 9 JUL the city garrison and many of the remaining civilian volunteers began repairing the city's walls.

Interlude 1: The Walls of Vienna

The last time we discussed an Ottoman siege it was over 200 years earlier, when Mehmet II took what was then Constantinople in 1453. One of the things we talked about was the urban legend of the Ottoman cannon and the Theodosian Walls; specifically, that the trope that the old medieval walls were destroyed by the Ottoman artillery just wasn't true. The Ottoman siege guns did some damage, yes, but cannon artillery just wasn't good enough in the 15th Century to hammer down a strongly-built stone fortress wall.

By the 17th Century things had changed. Artillery had changed, and was now powerful and accurate enough to do just that.

So fortress walls had changed, too.

(Both the guns and the walls kept changing, by the way, all the way up until aircraft made fixed forts deathtraps for their defenders; here's the descendants of our Austrian Imperials with a 305mm Skoda siege howitzer in 1914)

Let's step back a minute.

Remember how we talked about how you, as a besieger, could get into a fortified place, a walled town or citadel. There were still, in 1683, only three ways:

1 - over - escalade, throwing a ladder against the wall (or rolling a big ol' mobile tower up to it) - which was quick but damned deadly for the attacker;

2 - under - mining, digging a tunnel under the wall and the collapsing it and bringing the wall down (or, by the 17th Century, packing it with explosives and blowing the wall sky-high), or

3 - through - either by using some sort of kinetic weapon like a ram, or a stone-thrower, or (as now) a cannon to batter down the wall...or by getting one of the defenders to open a door for you.

That was it. Over, under, or through.

Well...there was another way that didn't involve actually getting inside by force. You could camp out around the fortress and wait for the garrison to run out of food. But- assuming that the commander of the garrison knew his business - that was painfully slow, and slow, in sieges, wasn't good.

Because a town besieged would fall.

That sounds over-confident, but it was simple logistics. The defenders had limits; limits on their manpower, limits on their food, munitions, limits on how long they could stave off disease. Provided the besieger didn't fuck up, or the weather didn't turn bad, or some unforeseen disaster strike a siege would have only one conclusion.

That's why the defender was relying on his pals to show up in force and relieve him. The one thing that would change the brutal incremental calculus of siege warfare was a second defender force arriving outside the walls. Then the besieger would be in a vise, with the enemy fortress in front and the enemy field force behind.

So the trick in winning a defensive siege was to hang on long enough, and make the attack costly enough, that the besieger would be caught in that vise and crushed.

And the trick for winning an offensive siege was to figure out the quickest way to get the defenders to give up, or get inside and butcher them, before the relieving force showed up or winter set int.

The improvements in cannon artillery meant that in order to hold on long enough the defenders had to change the way they built their fortifications. Here's a good example; here's a cross-section through the Theodosian Walls of Constantinople:

Don't get me wrong; these suckers were the gold standard of fortress construction in 1400. Thick, high (to make them tough to climb), studded with towers to provide fire down the length of the "wall" bits between the towers (called "curtain walls") to kill people hanging about at the bottom or trying to climb up. The other strength was that you had a "defense in depth", layers inside layers of walls and other defensive structures; to get inside you had to first cross the moat, then get over the palisade (the small wall just indie the moat), then scale (or batter down, or mine) two wall sections, each one higher than the other (so even if you took the outer wall you were exposed to arrow or engine fire from the inner).

But.

The Theodosian wall had a single, fatal weakness. To high-velocity cannon fire, they were just a vertical pile of stone.

Vertical, meaning that if you smashed the bottom the top would tumble down, and stone, meaning that when you hit it with a fast-moving iron or steel projectile it would shatter. Give a competent artilleryman a couple of weeks and a depot-full of ammunition and all you'd have let of the mighty Walls of Theodosius would be a heap of rubble.

That's why, beginning in the middle of the 15th Century - that is, when cannon artillery began to mature - you began to see what was known as the "bastion fort" all over Europe.

The walls of these forts were lower, and thicker, than the old medieval walls. They were often made of brick, or, better yet, rammed earth, which soaks up cannon fire, crumbling in place around the shot rather than shattering.

The old-fashioned square or round towers were replaced by pointed bastions, which served the same purpose - to provide enfilading fire along the curtain walls between the bastions - but without providing the dead space in front of the tower/bastion that an enemy could hide in.

Because the walls had to be lower, the ground outside the walls and bastions had to be lower still, so a deep moat (wet, or dry, depending on the availability of water) would be dug at the base of the walls, and the spoil thrown up onto a long slope called a glacis leading up to the moat. This slope provided cover from direct fire for the base of the walls as well as, usually, leading up to the outermost line of defense that would be located right along the top edge of the moat.

Here's a typical profile of one of these bastion forts:

But what about the multiple lines of defense we had with the Theodosian Walls?

Well, they're there, just not shown in this section. In fact, most 17th Century fortresses had layers within layers; parapets along the top of the glacis, then ravelins (triangle-shaped mini-forts), half-bastions, hornworks, and other outer works, then the actual bastion-and-curtain-wall fortress walls themselves. Here's a schematic:

The original city walls of Vienna actually date to Roman times, when the Legio XIII Gemina built a standard single-legion fortified camp at what they called Vindobona.

This, by the way, wasn't the Big City in Roman times; that was Carnuntum, further down the Danube in the little town of Bad Deutsch-Altenburg. The original Vindobona fell on hard times when the Romans did, but the place seems to have been a town (or city) so long as people lived there, which has been continuously since pre-Roman times until today.

The early medieval city walls followed the trace of the old legion fort, suggesting that something, if only the foundations, remained.

Vienna was part of Bavaria, believe it or not, within the HRE, during the High Middle Ages, part of the Bavarian "East March", meaning it was on the frontier of the civilized lands. So as a frontier fort the walls must have been maintained against the Magyars and other horsemen out of the East.

The big infrastructure project between Roman times and our siege came in the 13th Century, when the local duke's guys came across Richard Plantagenet, the famous "Lionheart", holed up in a whorehouse in the town of Erdberg near Vienna two days before Christmas, 1192. The duke was jolly as Saint Nick himself to nab the probably-lionhearted-but-certainly-rockheaded Plantagenet trying to sneak through his turf, and proceeded to sell Richard's royal ass to the highest bidder...which came to damn near ten tons of silver.

Here's the royal captive groveling at the Holy Roman Emperor's feet, by the way. Richard may have been a hero to storytellers back in England, but he wasn't a real popular guy in Austria, as you can tell from the way his captors show him wriggling pathetically at Henry's feet in his long johns.

This haul financed construction of some big, new walls and allowed Vienna to grow into the principal city of the region by the time it was pictured on the Nuremberg Chronicle in 1453:

It was these medieval walls that Suleiman stared at in frustration in 1529. The Hapsburg councilors knew how narrow their escape had been, though, and began adding modern bastion-fort defenses to the old walls as best they could.

Here's what the city defenses looked like at the time of the siege 150-odd years later:

You can see that the defenses had been upgraded along most of the city walls; the weakest point was in the northeast, right along the Danube, the "Great" and "Small Gonzaga" bastions. The riverbank there was just too close to the old city to allow for much improvement. The only real hope was that the river was too deep for the wall there to be undermined, and the logistics of a combined river-crossing and escalade were a besieger's nightmare.

To the south, east, and southeast - from the Danube to the Carinthian Gate - an attacker faced the same problem; the walls weren't that tough, but the water obstacles were a real nuisance.

So to a logical attacker that limited the engagement area to the dry-moat section between the Carinthian bastion and the Scottish ("Schotten") Gate.

Within this section all the observers, including those present at the time, seem to agree that the weakest piece of the defenses was the section between the Burg bastion and the Löbl bastion. This was because the bastions themselves were too far apart to provide good interlocking fields of fire. The ditch was dry, and the ground was cobbly riverwash, relatively easy for the Ottoman miners to tunnel.

Wheatcroft (2008) remarks;

"Close to the Hofburg Palace there had been a curious mismatch during the different phases of building the new fortification. They did not align properly with the structures on either side...(t)his section was built in the 1540s and should have been built further out from the old city wall.The garrison and volunteers worked furiously to strengthen the defenses along the southwest side. In particular, the palisade - the outermost defensive line - was repaired having been allowed to deteriorate. These repairs consisted of

Immediately behind this weak sector was a complex of buildings that made up the imperial palace and, beyond it, the maze of city streets. Once an enemy had broken through at the point there was little space to build emergency defenses behind any of the breaches in the curtain wall: a determined assault would be hard to stop. The inherent weakness was heightened by a circumstantial flaw: the every close proximity of the suburbs, notably the garden and its buildings attached to the grand summer palace of Count Trustson. These extended to within a few hundred yards of the outer city defenses. The...glacis had been dug up...to provide pleasure gardens and productive vegetable plots and this well-tilled earth would make it very easy going for the Turkish sappers..."

"...hammering long timbers into the earth to make a continuous palisade along the crumbling outer line of defense...(which) in many places...had fallen over or rotted in the ground. In other places, holes had been made to that the Viennese could find an easier route...rather than use the gates.Other engineering work included building blockhouses and minor works to reinforce the ravelins and bastions.

These timbers were as thick as ships' masts, evenly spaced and buried deep in the ground. The height above the ground varied, never less than six foot tall, sometimes more than eight. Only a direct hit from a cannonball could obliterate them...(y)et even their battered stumps, used as shelter by musketeers, could halt an assault. (Wheatcroft, 2008)"

And burning the suburbs.

Once that had been done Vienna was as ready as it could be for the arrival of the Ottoman army.

The Engagement:

The Imperial field force fought a brisk meeting engagement with the Ottoman advance screen and cavalry vanguard near Petronell on 8 JUL. A Tatar patrol caught part of Lorraine's rear security elements (and, my guess is, some baggage train; Tatars would probably have avoided a pure troop unit) and tied into them.

The Imperials drove off the irregular cavalry but were then caught in disorder by a unit or units of regular sipahi cavalry which tore up the Imperial troops and threatened to overrun the entire force until Lorraine himself showed up with cavalry to see off the Ottomans. The Imperial rearguard left the field in good order but having taken worse than they dealt out.

The Imperial troops continued through Vienna, leaving only a small mounted security element in Leopoldstadt on the Prater Island across the Danube canal.

The garrison was on its own.

On 14 JUL the Ottoman main body arrived outside Vienna. Vaelckeren's diary says that

"...a whole army of Turks, with an incredible number of horses, wagons, buffalos and camels, appeared moving towards Vienna over the hill by St. Mark's Church...they immediately spread themselves from the banks of the Danube through which circuit they continued encamping themselves till late at night."Two days later a force of sipahi cavalry forded the Danube canal and drove off the Imperial dragoons and Polish mercenary heavy horse posted on Prater Island. The city was now fully encircled.

Less about 10,000 troops posted to mask the fortress of Győr

(and the Tatars, useless for siege work, that had been set out to raid westwards into Austria...)

...the entire Ottoman force was set down in front of Vienna to break the walls and take the city.

16 JUL to 7 AUG 1683 - Defending the Palisade

As puny as it might have seemed compared to the hulking ravelins and bastions behind it, the wooden palisade wall turned out to be a hell of a tough obstacle for the Ottoman troops. Starhemberg left a notional force on the main walls to man the palisade before the Ottoman trenches, and the first assaults on this obstacle weren't siegecraft but pure old-school Ottoman ferocity; janissary infantry attempting to overrun the palisade by sheer mass and speed, resisted by Imperial musketeers and pikemen fighting with swords, cut-down pikes, and hunting spears.

Grenades, which at this point were nothing more than clay or glass or metal pots of gunpowder with fuses, were thrown by both sides. The result would be a bloody pileup outside the palisade with both sides blasting each other with muskets at point-blank range, ripped apart by grenades and artillery fire, and impaled on pikes and spears.

The Ottoman gunners would precede each assault with a prep fire, trying to batter down the wooden wall and open breaches, but the sloping glacis made it impossible for the flat-trajectory cannon of the time to "shoot-in" the assault teams; the storming parties would be in the line of fire for much of the distance to the palisade. The defenders' artillery would hammer the attack force until it closed on the palisade, and then resumed firing to harry the janissaries as they retreated.

The Imperial defense proved too tough for the Ottomans to carry by storm, so the mine crews went to work. The first mine explosions cratered the palisade and piled up mounds of soil, but a mixed force of Imperial infantry and dismounted cavalry of the Dupignis Regiment drove back the assault that tried to exploit the crater, "...cutting off many of their Heads, fixed them on Stakes and Palisadoes on the counterscarp in sight of the Enemy (Valckeren, 1684, in Wheatcraft, 2008)

By early August the siege engineers had built up raised earth firing platforms overlooking the palisade that allowed the musket fire to clear a stretch of palisade. Under this covering fire cannon were advanced to smash the timbers, and finally on 7 AUG a janissary assault grenaded its' way into through the palisade in front of the ravelin between the Burg and Löbl bastions.

Interlude 2: The Missing Guns of August

We just talked about how fortress walls had to change when cannon artillery changed, grew up from its medieval childhood and began to dominate the battlefields of Europe. And, while that is true, it brings up a problem we touched on earlier; the Ottoman besiegers didn't have that artillery.

Oh, Kara Mustapha brought what cannon he could. But the poor roads, inadequate preparations, and late start that the Ottoman force made meant that when it arrived before Vienna it simply didn't have the sort of weight of metal that would have made short work of the poorly upgraded city walls. The relatively small fieldpieces that accompanied the Ottoman forces just couldn't throw enough force at even the second-rate defenses they faced.

17th Century siege cannon typically threw a 24-pound ball or larger. A 24-pound mass times an acceleration of, say, about 10,000 feet per second per second (which is a very slow acceleration, by the way - the acceleration of a 9mm handgun bullet is typically around 96,000 feet per second per second) could deliver nearly 240,000 foot-pounds of energy to its target. Compare that to a 6-pound ball, which at the same velocity imparts only about 60,000 foot-pounds.

So for siege guns, size really is important.

Without the siege batteries the Ottomans before Vienna had to resort to the older, slower forms of battering down walls, principally mining.

At least explosives had improved that form of siegecraft. Early mines had to rely on digging a large enough cavern under the wall or tower - which would be braced with timbers - and then firing the timbers, the idea being that the cavern would then collapse and bring down the wall above it. In practice this was a tricky proposition, prone to either collapse prematurely under the weight of the wall or fail to remove enough of the bearing soil to drop the wall sufficiently to topple it.

Gunpowder solved the problem by simply blasting a hole in the ground and, if large enough, the wall overhead. These explosive mines were a standard trick in siege warfare all the way up to the First World War. The process of emplacing the mine, however, was still more slow and difficult, and the process much less predictable, than knocking a wall down with siege artillery.

We'll talk about this again when we get to the Battle of Kahlenberg, but the failure of the Ottoman Topçu Ocağı before Vienna is a symptom of the technological breakdown of the Ottoman Empire.

In 1453 the Ottomans had been the technological Young Turks, and their mastery of artillery had shocked the Byzantines and Westerners raised on knighthood and the culture of the sword.

But 1683 the Ottomans had fallen behind. Western gunners were getting better and better; the innovations in cannon artillery would emerge from Europe into the age of steel barrels and chemical propellants. Ottoman siege warfare was still stuck in the 15th Century as European cannon had entered the 17th.

Vienna is important as an indication of how far the Ottomans had fallen from their brash morning arrival out of the steppes of Central Asia.

7 AUG to 8 SEP - Up Against The Walls

From here the story of the siege begins to resemble something we would recognize, if only because the pure human misery resembles similar horrors of the 20th Century such as the sieges of Leningrad and Stalingrad.

Daily the gunners would go to work, the Ottomans hammering at the Imperial works, the Imperials targeting the batteries, or the Ottoman infantry working at the saps, the heads of the trenches slowly working towards the base of the walls. Snipers; Serbian or Bosniak on the Ottoman side, Jäger, professional hunters or gamekeepers on Austrian estates for the Imperials, waited patiently for an exposed head or body to kill individuals.

The Ottoman sappers dug towards the walls, the miners dug underneath them, while the Imperial sortie-parties did what they could to kill the sappers and wreck the works, collapsing saps and parallels, wrecking gabion and tools.

Under the ground the mine and countermine parties fought a bizarre sort of subterranean war, the Ottomans racing desperately to burrow beneath their target stretch of wall, set and detonate their charge, while the Imperial countermine parties dug frantically to intercept the Ottoman tunnel. Typically the attackers succeeded; one or two mines were detonated nearly every single day of the siege. Many of them did little damage to the heavy brick walls, but not all.

In what seems even more familiar to us, the Ottoman artillery would occasionally throw a round into the city itself. On 1 AUG a solid roundshot came through one of the tall windows of St. Stephen's Cathedral during mass; one poor bastard lost both legs to stone and shot splinters.

Both attackers and defenders grew morally and physically ill, a condition that the gruesome slog in the trenches must have been partially responsible. Almost everyone had some form of dysentery; the Imperial commander, Starhemberg, is said to have been so badly stricken that he could barely walk. The field sanitation of the Ottoman encampment, usually far better than that of a similar European force, began to break down. "Dead animals were swelling and rotting under the heat of the sun, and even human corpses, buried in shallow graves, began to push through the loose soil above them." (Wheatcroft, 2008)

The two sides' leaders' temperaments became a significant factor. Starhemberg, "wearing a cavalryman's buff leather coat after he had been wounded by flying splinters...spent much of each day on the walls...(Wheatcroft, 2008)" and was both a personal example to, and a judicious tactical commander of, his troopers.

Kara Mustapha "...seems to have been better at chastising than encouraging. He handled his commanders badly; each one...received only peremptory commands to push their men harder..."(Wheatcroft, 2008).

Worse, for the Ottomans, Mustapha was singlemindedly fixated on the siege before him. He neither sought out, nor listened to, the intelligence brought in by his Tatar scouts. He considered the Imperials a spent force, and disregarded any of the sort of typical precautions a cautious siege commander would taken, such as constructing "lines of contravallation"; field fortifications to defend the siege camp from a relieving force.

The siege dragged on and on into late August. Assault, sortie, daily bombardment, mining. The Ottoman mines slowly reduced the ravelin between the Burg and Löbl bastions; by late August it was barely extant, shattered by mines, hammered by artillery, reeking with corpses. The frightful part of this was that once the ravelin was taken the inner wall behind it was dangerously weak.

"...on the Burg bastion a solid bunker filled up much of the surface space, impeding men and guns from moving speedily on of off the platform, while the Löbl was shoddily built. Destroy the ravelin, attack the Burg and Löbl bastions more or less at the same time, and then breach the curtain wall between the two. It was impossible to move in men and guns fast enough to reinforce the two...and Starhemberg could never know precisely where the fatal blow would fall. (Wheatcroft, 2008)"Finally, on 28 and 29 AUG, a combination of mining and assault destroyed the functional capacity of the ravelin. A sad little entrenchment at the crest of what was nothing more than a heap of soil remained in Imperial control until 3 SEP, but without cannon or more than a handful of defenders it served no military purpose.

On 4 SEP a massive mine brought down thirty feet of the southwest face of the Burg bastion. A full Janissary regiment assaulted over the debris but had the bad luck to have timed their assault just at guard relief on the bastion; both the relieved and relieving watch were still on the bastion and shot down the attackers.

Improvised obstacles - spears, sword-blades, even sharpened staves driven through a timber beam - were thrown down into the breach. Fieldpieces were shoved around to face the assault and fired at point-blank range. Grenades from both sides ripped men apart.

The fight went on from 1400 to 1600 hours without let-up. Starhemberg and his staff led from the front. Ottoman artillery and mortar fire were directed on the fighting top of the bastion while the janissary assault force continued to push onto it; the supporting fire killed attackers and defenders indiscriminately.

The fighting didn't die down completely until nightfall when the attackers pulled back to their trenches and the defenders spent an exhausted night palisading the breach in the bastion ahead of another day's fighting.

At this point the garrison was down to 60% effectives (the modern U.S. Army considers a unit "combat-ineffective" when it has lost 30% of it's original numbers).

Civilians were being shoved into gaps in the battalions because there simply weren't any trained reserves to be had.

Two days later, 6 SEP 1683, three mines went off together under the southeast face of the Löbl bastion, the wall that faced the Burg bastion. The wall itself was destroyed, top to bottom, and all the cannon on that side of the bastion were either destroyed in the blast or thrown down into the ditch below.

Again the assault waves, roaring behind the horsetail standards, scrambled up the debris-pile to throw themselves against the remaining defenders of the bastion and the troops from the nearest sections of the walls that were hurried to support them. This time the fight lasted all day; musketeer and pikeman against janissary and dismounted sipahi cavalryman. Musket butt, spear, and yatağan; grenade and knife and bare hands.

The attack force was, again, pushed off the wall as night fell.

The insoluble problem for the Imperial defenders was one of simple odds. The Ottoman force had, by this time, lost perhaps 10 to 15,000 killed and wounded, the defenders 4 to 6,000. But 15,000 casualties were barely 15% of the strength of the Ottoman attackers; 4,000 was almost half of the defenders'.