Hydaspes (or "The Hydaspes") Date: May, 326 BCE

Forces Engaged: Μακεδονία; Macedonia (or, properly, the empire assembled by

Αλέξανδρος Γʹ ὁ Μακεδών, Alexander III, king of Macedonia and emperor of Persia)

Before we begin, it's worth noting here that it's very likely that the Alexandrine army that forced passage of the Hydaspes, or, as it's called today the Jhelum, River was the first truly "imperial" force in history.

Surely earlier polities that were in the business of expanding into their neighbors' homes had knocked together polyglot assemblies of people they'd snatched up in the process. But the empire of Alexander was an order or three of magnitude above that, and by the time it reached out to the edge of the Indian subcontinent had incorporated a ridiculously heterogeneous congeries of people under the notion of a "Macedonian" empire.

The hard core was still the hard men from the rocky north of Greece. But Alexander led what we can generally term a "multinational force", with all that implies.

In May 326, the imperial army broke down into two (or three) subunits - let's call them "task forces" to keep my modern US Army brain happy - based on their roles in the imperial operational plan.

Task Force Alexander (the maneuver element): The primary assault force that crossed the Hydaspes was built around the core of Alexander's original army that brought him out of the hills of northern Greece; the spear-and-shield heavy infantry and the companion cavalry of Macedon. These, in turn were divided into three subunits, two of infantry, and one of cavalry:

Heavy infantry (around 6,000 some-sort-of-polearm-and-shield infantry):

- Hypaspists (Ὑπασπιστής) - the equivalent of a modern brigade composed of roughly 3,000 elite spear-and-shield heavy infantry that are supposed to have fought in the "traditional" hoplite panoply; the infantry equivalent of the "companion" cavalry. The hypaspist gear is described as distinct from the "regular" Macedonian phalanx by the use of the older dory (δόρυ) single-handed spear instead of the much longer sarissa (σάρισα) pike. Commanded by Seleuces

Supposedly the idea was that these guys would provide flank (particularly the right, unshielded, flank)-and-rear security for the dangerous-to-get-in-front-of-but-not-so-dangerous-in-the-other-three-directions Macedonian phalanx but were still well armed-and-armored enough to get stuck into close combat (except against the front of another phalanx...).

Further broken down into three 1,000-man "chiliarchies" (χιλιαρχία), the senior of which was effectively the imperial "foot guards".

- Taxeis of Antigenes - approximately 1,500 pike-and-shield heavy infantry. This was the famous Macedonian phalanx (φάλαγξ). The taxeis was the umbrella organization - usually "geographic", that is, made up of guys from the same region - and the actual "phalanx" was made up of blocks called syntagmata, each sixteen files (called lochoi, λόχος) wide and sixteen ranks deep for a total of about 250 troopers per block. Call that a "company", figure 250 as a rough strength, and you get about six of these syntagmata companies for the taxeis battalion. Commanded by the above-named Antigenes (Ἀντιγένης), who, it's worth noting, went waaaay back, having been an officer under Al's daddy Philip of Macedon. His story - at least the end of his story - is also kind of horribly fascinating, which I'll get to at the end of this beast.

One thing to note here is that the actual protective kit of the sarissa-armed Macedonian phalangites has been much-debated and, to make things more confusing, appears to have changed over time. The single biggest difference in protection from the earlier hoplite phalanx would have been the shield.

The older hoplon (ὅπλον, or aspis,ἀσπίς) was nearly three feet in diameter and was carried on the left arm and shoulder, which was possible while stabbing or thrusting the dory spear with the right.

But the two-handed pike meant that the guys in the Macedonian phalanx couldn't actually look like the ferocious picture above with their shields facing front. They must have slung a somewhat smaller shield from a strap over their arm, or over their left shoulder and around their neck. So far as I know no actual artifacts of this piece of kit have been found, so we're left to try and deduce what it looked like and how it worked from descriptions and depictions. The Wiki entry for "phalanx" actually has a good little discussion of the scholarship on this question:

"Because of its great length, weight and different balance, a sarissa was wielded two-handed. This meant that the aspis was no longer a practical defence. Instead, the phalangites strapped a smaller pelte shield (usually reserved for peltasts, light skirmishers) to their left forearm.

Recent theories, including examination of ancient frescoes depicting full sets of weapons and armor, claim that the shields used were actually larger than the pelte but smaller than the aspis, hanging by leather strap(s) from the left shoulder or from both shoulders. The shield would retain handling straps in the inner curve, to be handled like a (smaller) aspis if the fight progressed to sword-wielding. Although in both shield size assumptions this reduced the shield wall, the extreme length of the spear kept the enemy at a greater distance..."

Every ancient source seems to agree that about the remainder of the phalanx-kit; greaves to protect the lower legs, a helmet, and some sort of torso armor. We have examples of metal breastplates (called thorax, θώραξ in Greek) which were similar to many other historical cuirass-type vests, so we know these were used.

The other body armor, however, is known today as a "linothorax" (although we don't know what a Macedonian of the 4th Century BCE would have called it, though probably the Greek equivalent of "fucking battle-rattle", if I know my infantrymen). Supposedly this thing was made of sheets of fabric layered, probably glued, together. You can see the advantages in weight and, possibly, in the reduction of the "cook-pot" factor of wearing metal armor in the heat and the "icebox" factor in the cold. Whether the loss of protection was worth the increase in mobility and comfort is a question. A Professor Aldrete of the University of Wisconsin (Green Bay) has done some interesting work on trying to reconstruct this thing, and he's worth a visit.

Yike! Sorry for the long digression. I get a little carried away with the history. Back to the order of battle.

- Taxeis of Cleitus - roughly 1,500 heavy pike-and-shield infantry, as Antigenes, above. Commanded by one of the two "Cleitus" officers we know of as part of Alexander's retinue, presumably Κλεῖτος ὁ λευκός, "Cleitus the White" seeing as how Al had put a spear through "Cleitus the Black" two years earlier.

Light Infantry (roughly 4,000 javelin-and-shield infantry)

- Agrianian peltasts ( πελταστής) - About 1,000 light infantry armed with throwing spears/javelins (akontio, ακόντιο) and a unique crescent-shaped light (often wicker) shield called a pelte (πέλτη).

These guys were the equivalent of the companions and the hypaspists for the light infantry; the elite unit that was often round at the right-end, the "position of honor", of the Macedonian battleline.

They were also among the first of the "imperial" troops, hailing not from Greece proper but from the northern hills of what are today western Bulgaria and southeastern Serbia, so, another damned thing from the Balkans, basically.

Like all light infantry, they would scout before the main army and then, in close combat, screen the sides of the infantry and cavalry core, screen in retreat and pursue in victory.

- Cretan foot archers - 1,000 light missile infantry. Crete was known for it's archery, so presumably these troops were there to perform similar tasks as the Agrianians only with arrows rather than javelins. Probably mercenary troops, since Crete was already known for their soldiering-for-hire by this time. The one oddball thing noted about the Cretans was their lugging around a small shield. I can't find anyone who explains why, though, unless they intended to stick around long enough to come to handstrokes, which seems like a bad idea for a bow specialist.

- Macedonian foot archers - 1,000 light missile infantry. As the Cretans only probably without the little shield thing.

- Thracian peltasts - 1,000 javelin-and-shield light infantry. As the Agrianians, may have been "allies" although like the Cretans probably mercenaries.

Cavalry (Something probably on the order of about 5,000 cavalry, a mix of 1,000 light missile cavalry, 1,700 light missile and light to medium cavalry, and 2,300 what would probably be considered medium cavalry by the standards of Europe in the 1400s but was "heavy" in pre-medieval terms)

By Alexander's time the horse soldier had become the "combat arm of decision". The infantry dominance of "classical" Greece that had been subsumed by Macedon in the mid-4th Century BCE was giving way to Alexander's preference for personal leadership at the head of his bodyguard squadron of the "companion" (hetairoi, ἑταῖροι) cavalry that, in turn, led the remainder of the elite Macedonian mounted arm, to charge lance-in-hand against formed enemy formations.

Keep in mind how unusual this was, both before and since Alexander's time. Cavalry were not as helpless without stirrups as the first Victorian historians thought they were. But gripping the barrel of a moving horse with only one's legs didn't make for a particularly stable platform from which to swing a sword or couch a lance.

Therefore most horsemen in the ancient world were missile troops, either archers - and we'll see some of those here - or javelin-throwers. And it's worth noting that the ascendance of the Macedonian cavalry was brief; by the time the Hellenistic armies fall one after another to the Romans the cavalry is once again relegated to the fringes of the battle. But for the pony soldiers, Alexander's campaigns were a brief, bright moment in a long slog towards the glory of the armored knight and man-at-arms of the high medieval.

- Companion cavalry - 2,300 heavy cavalry in five hipparchies (ἱππαρχία)

- Agema (Guard) cavalry squadron (individual squadrons were called "ile" in Greek) - 300 cavalry armed with a xyston (ξυστόν) two-handed spear or lance with a sword of some type (either the leaf-bladed xiphos or more likely the kukri-like kopis) and armored with a torso-protection and a helmet...

(Another quick digression here on the subject of helmets. Think "Greek helmet" and the first thing that comes to your mind is probably what you think if when you think "Spartan", the classical or "Corinthian" helmet, this thing:

But, while fine for a guy poking at someone with a long stick inside a tight formation with a bunch of other guys, the field of view from this closed helmet is way too small for a fast-moving horseman. The typical hard hat worn by the 4th Century companion cavalryman would have been these:

"Boeotian"-type helmets, the metal equivalent of a folded-brim sun hat, that would have provided enough protection while giving the wearer much better situational awareness. Here he is with his full kit...)

So an initial total of 6,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry under the direct command of the force commander Alexander III, Basileus of Macedon, Hegemon of the Hellenic League, Shahanshah of Persia, Pharaoh of Egypt, Lord of Asia.

Task Force Craterus (the fixing element): Alexander's scheme of maneuver depended on keeping his opponent's attention fixed across the Hydaspes where the imperial army was supposed to be stymied by one of the most difficult of military maneuvers, an opposed river crossing. To do this he left a significant part of his force, including a main element that was supposed to simulate the whole army, as well as a screen of units to keep contact between the fixing element and the maneuver element.

The "fixing" force included the following:

Infantry: (approximately 8,000 mixed infantry divided into heavy and a mixture of allied units we don't really understand)

- Taxeis of Alcetas - 1,500 pike-and-shield heavy infantry (as Antigenes, above)

- Taxeis of Polyperchon - 1,500 pike-and-shield heavy infantry (as Antigenes, above)

- Levies of "Taxila" - something around 5,000 assorted troops from the allied Punjabi polity that we know from the capital of Takhkhasilā, (तक्षशिला), known to the Macedonians as Τάξιλα.

We'll talk about this in the Campaign section in a bit, but like most imperial colonizers Alexander had picked up bits and pieces of the surrounding areas as troops (levied or as allies), provisions, camp-followers, or some combination of all the above. These included the forces of the Punjabi ruler of the area that we're told in Arrian extended between the Indus (because he's first mentioned after the Macedonians cross that river) to the Jhelum (which is where we meet our opponents the Pauravians).

The name of the individual who seems to have been in charge of whatever-this-region was is often given as "Taxila" - the Greek chroniclers often confuse the man with the place. Two of the Roman historians don't, but Diodorus Siculus (we'll get to him in Sources) calls him "Mophis" after saying this it was his dad who was "Taxiles" and Quintus Curtius Rufus calls him "Omphis". In his Wiki entry (under "Taxiles") we are informed that his name was actually "Ambhi"; the citation for this is Heckel (2003), but what his source is I don't know.

We have no idea how these people were armed and equipped other than presumably similar to the Pauravian troops under Porus, which we'll discuss in a bit, so a combination of medium infantry, including "medium" archers firing a heavy bamboo bow, light to medium cavalry, and likely some number of elephants, although how many we have no idea.

Let's assume that the proportions were similar to Porus' army, so about 6:1 infantry to cavalry and one-sixth the number of elephants. That works out to about 4,000 infantry, 700 or so cavalry, and something like 20-40 elephants. Although Porus fielded chariots none of the sources mention them on the Macedonian side, so presumably the Taxila forces didn't bring any.

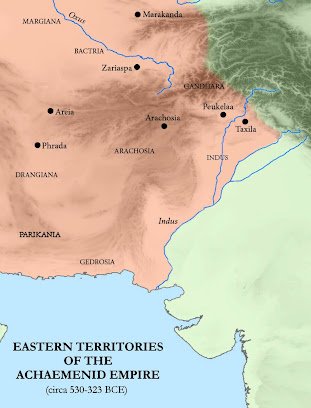

Cavalry: (numbers uncertain; at least 500 heavy companion cavalry and some unknown number of allied/levied cavalry from the eastern Persian areas of Arachosia and Parapamisa (now parts of eastern Iran, Afghanistan, and western Pakistan)

- Regular cavalry squadron - 500 heavy lance cavalry under Craterus

- Allied cavalry - units and numbers unknown (1,000?) Arachosian and Parapamisidae cavalry.

So probably a total of 9,000 to 10,000, largely heavy infantry with a mix of companion and allied cavalry under Craterus

Task Force Who-the-fuck-knows (the screening element): included a mix of heavy infantry and mercenary (medium?) cavalry, including:

Infantry: (possibly 4,500 to 5,500 heavy pike-and-shield and spear-and-shield infantry...with a caveat)

- Taxeis of Meleager - roughly 1,500 heavy pike-and-shield infantry, as Antigenes, above.

- Taxeis of Attalus - roughly 1,500 heavy pike-and-shield infantry, as Antigenes, above.

- Taxeis of Gorgias - roughly 1,500 heavy pike-and-shield infantry, as Antigenes, above.

- Greek mercenary infantry - probably about 500-1,000 spear-and-shield hoplite infantry

(Note: It's worth noting here that Bosworth (1973) disagrees with this; his reading of Arrian - who is the only source for these dispositions - is that the listed officers were probably not in charge of a complete phalanx unit but were detailed off to keep track of the mercenary infantry and cavalry without their troops.

Bosworth (1973) points out the "absurdity" of Alexander crossing with only two taxeis and leaving five on the far side of the river. But, again, we can't be sure.

Cavalry: (unknown number of Greek mercenary cavalry; maybe 500-1,000?).

We don't know who, if anyone, was in charge of this element; likely nobody, given that their assignment was to simply screen in place along the near side of the Hydaspes until the crossing was successful. And, as discussed above, we're not sure where those phalangites were, either.

So, taking all three task forces together; roughly 24,000 infantry, 7,500 cavalry, 20-40 elephants under the overall command of Alexander III of Macedon etc. etc...

Kingdom (?) of Paurava (पौरव) - All we know about the force commanded by Porus (or Poros, Πῶρος in Greek) that met the Macedonian Empire along the banks of the Jhelum/Hydaspes is what the imperial accounts tell us. That's often the case in imperial war, but it's made more frustrating by the fact that so far as we know the Pauravians were also a sophisticated literate society that must have kept records of what happened that day in May, but those records have been lost over the succeeding 2,300 years and change.

Arrian, who gives us by far the best account of the actual fighting, tells us this:

1) He cites Aristobulus as recounting that a Pauravian reaction force of somewhere around 60 chariots under one of Porus' kids (let's call him "Kid" so we can call this thing "KidForce" in the British tradition) was dispatched from the main force overwatching the river to find out what the fuck these irritating strangers were up to.

2) But Arrian then says that Ptolemy, "with whom I agree", says that Kid arrived with 200 chariots and 2,000 cavalry, so we're left to presume that this is the correct number.

3) When this scouting/reaction force failed to stop their enemies (and presumably provided a full sitrep that they were across the river in strength) the Pauravian commander "left a few of the elephants together with small army" - we're not told how small - and moved the bulk of his force to confront the imperials. This consisted of:

- 30,000 "choice" infantry, so presumably the bulk of his kshatriya effectives; sword-and-shield, spear-and-shield, and medium-to-heavy missile infantry,

- 4,000 cavalry, presumably a mixture of light and medium/heavy, although what mix we're not told other than none of the Greek sources talk about armored horsemen, so presumably there were none, or only a very few of the wealthiest Pauravians. Arrian says this was "all" the Pauravian cavalry, so at least we know that,

- 300 chariots, also described as "all" even though Arrian has already told us that he believes Ptolemy when the Alexandrine officer says that the earlier reaction force included 200 more, so the 300 vehicles weren't "all" but "all that were left", possibly including survivors from the earlier encounter, and

- 200 elephants, which, since Arrian has described the number of elephants left facing Craterus as "few", leaves us to assume that the original total pachyderm count was under 300. Let's say 250 and call it good.

Again, we'll get to this in Sources, but here's what the other four main accounts of this engagement tell us about the Pauravian force:

Plutarch cites Alexander's correspondence as his source of first-hand account, and says: "Porus stationed his elephants on the opposite bank and kept continual watch of the crossing." - that's it for the main force.

He then mentions the first encounter with the Pauravian reaction force as including "...a thousand of the enemy's horsemen and sixty of

their chariots..." but whether this is the full strength or only the number which Alexander's element defeated, we're not informed. The sixty chariots number agrees with Aristobulus, though, so we can't be sure whether to believe Plutarch - who is supposedly giving us Alexander's eyewitness account of the earlier engagement - or Arrian, whose numbers come from Ptolemy, whose location during that engagement we're not sure of, since Arrian doesn't mention his actions otherwise.

Finally, when Porus moves to confront the imperial maneuver element Plutarch says he takes "...all his forces, except the part he left behind to impede the crossing of the remaining Macedonians."

That's it for Plutarch.

Diodorus Siculus is much more succinct. He gives no details at all about the first meeting engagement between Alexander's element and KidForce, just the main engagement, but he does give us overall numbers for the Pauravians: "He (Porus) had more than fifty thousand infantry, about three thousand cavalry, more than a thousand chariots of war, and one hundred and thirty elephants."

We've already got a problem here, seeing as if Diodorus' total infantry numbers are right (and so are Arrian's for the Pauravian reaction force) the troops left guarding the ford weren't a "small" army as Arrian tells us but two-fifths, 40%, of the Pauravian infantry. If the rest of his numbers are right we've got a 25% discrepancy in cavalry strength between Dio's numbers and Arrian's, something between 50% and 300% (depending on whether Arrian is telling us that 300 chariots are "all" or he's forgetting to include Kiddo's 200) in chariot strength, and between 150% and 190% on the whole elephant thing.

Quintus Curtius Rufus gives us slightly different numbers, too. He gives KidForce a nominal strength of 100 chariots and 4,000 cavalry (and, it should be noted, says that the commander of this detachment was not Porus' son but his brother, Spitaces) and gives us the following strength for the main Pauravian force; 30,000 infantry, 300 chariots, and 85 elephants "of extraordinary strength of body" (no, duh? Elephants, right?). Oh, and he gives us Ptolemy's location - with Craterus on the near bank of the river, so not with Alexander and not an eyewitness to the KidForce engagement.

Justin, who is supposed to be the fifth of the major chroniclers of Alexander's campaigns, tells us literally nothing of the details of the engagement.

So here's what we've got.

The Pauravians bring something between 30,000 and 50,000 infantry to the bank of the Hydaspes. We have no further breakdown of these mooks, or anything particularly revealing about their kit. We get weird random details, like Quintus Curtius telling us that the Pauravian archers shot arrows "two cubits in length" that are shot with "more effort than effect".

Something between 3,000 and 4,000 cavalry of some type.

Somewhere between 300 and 1,000 chariots, and

Between 85 and 200-250 war elephants.

Since we have no way of reconciling all the discrepancies in the accounts here's my best guess.

I think it would be unlikely that the Pauravians would have had fewer overall numbers than the invaders. They were the locals, and they were defending their own lands, so you'd think that Porus would have little trouble getting his kshatriya to turn out to whack some damn Greeks. So I think the 30,000 infantry is a base number, the strength Porus pulled away from the ford to confront Alexander, and that he probably brought 35,000 to 40,000 all tolled.

The cavalry numbers aren't too far apart, so let's say about 3,500 horse.

I have no idea what to say about Diodorus' chariots other than I think he's fucking high. Nobody else comes up with that many, and if the Pauravian chariots had been swarming around like rats in a pile I think at least one of the other Greeks would have said something. So let's say somewhere between 300 and 500.

The elephant numbers are all over the place, and nobody seems to have a good idea how many Porus brought with him. Certainly there seems to have been at least something in the high two digits but less than 300, since nobody goes over that. Let's guess something like 150-200 and call it good.

So 35-40,000 light, missile, and medium-heavy infantry, 3,500 light to medium cavalry, 300-500 six-man chariots, and 150-200 war elephants under Porus, King of Paurava.

The Sources: Here's where we run into all the usual problems with ancient and medieval warfare, except that for once the people who wrote the stories weren't monks who didn't know one end of a spear from the other. Based on the citations of the extant source works, a whole bunch of people wrote first-hand accounts of what happened along the banks of the Jhelum in May of 326.

This includes the Great Man himself; Alexander - probably after taking over in Persia and learning about the Persian imperial record-keeping - set up the first "military history section", so to speak, in his GHQ.

That's a little too modernist. What we know are the names of several individuals (least one fairly junior (Diodotus) as well as a senior "chief secretary" (ἀρχιγραμματεύς) named Eumenes) who were attached directly to Alexander as a sort of combination subordinate officer-drinking buddy-staff pogue whose duties included writing up what was the equivalent of a staff duty officer's log. This thing, called Ephemerides from "ephemera" (ἐφημερίς) meaning journal or diary, recorded the boss' doings along with things like staff meetings and briefings, orders, copies of letters sent and received.

We know that this daybook (or "Royal Journal", as it's sometimes called) was kept in real time and traveled with Alexander on his campaigns; Plutarch (in his biography of Eumenes) mentions that the current copy of the daybook was burned in a tent fire and that Alexander "...actually wrote to his satraps and generals everywhere to send copies of the documents that had been destroyed, and ordered Eumenes to take them all in charge."

Supposedly after Alexander's death the official records ended up in Alexandria under the hand of Ptolemy and from there to the great Library, where they would have been accessible to the historians of the time. We can assume that such a valuable source of information about one of the people already recognized as towering was copied and those copies circulated, where they could be referred to not just by later writers but by Alexander's contemporaries who wrote their own accounts of the campaigns of their old boss.

These included several of Alexander's officers, including Ptolemy and Nearchus, and Alexander himself in the form of letters if we are to believe Plutarch (not all modern scholars agree, by the way).

Aristobulus, who was a field-grade officer, wrote up his war diary, as did Onesicritus, who steered Alexander's boat (and yes, I'm not kidding; he was the "chief pilot", ἀρχικυβερνήτης, and Arrian is pretty hard on him for pretending to be the admiral).

Several people who were not officers but were part of the conqueror's retinue, such as his "official historian" (until he pissed Al off, who threw him in the cooler where he died) Callisthenes, wrote or may have written accounts of what they saw and heard.

There's only one problem.

None of these original eyewitness accounts exist.

We don't have actual copies - either manuscript or in print - of, say, the Ephemeridies, or Ptolemy I Sotor's account of his adventures in Punjab. What we have are later authors citing them, so presumably they had some sort of manuscript copy of the journals and Ptolemy's work that have since been lost, and the same for the others.

The Wiki entry for "Historiography of Alexander the Great" lists a total of twenty of these lost chronicles, and keep in mind that's just what we know because they're cited in works we do still have.

What we have now are five principal secondary sources for the Hydaspes campaign, most of whom we've already mentioned:

The first, and most militarily useful, is Arrian of Nicomedea. He's a Romanized Greek, so he was fluent in the original texts, but he was also writing some time in the 2nd Century AD so more than 400 years later. His work, the Anabasis Alexandri, comes primarily from the lost Ptolemy account though as we discussed above, he also cites Aristobulus and Nearchus.

He's actually a decent historian, in that he's not afraid to cite his sources and (also as we discussed above) critique them when he thinks they fuck up. He gives the most useful tactical and grand tactical details of any of the five principal existing sources.

But here's where we have to go into the whole "manuscript trail" thing we talked about at length when we discussed Hattin, Tours, and in particular the fall of Constantinople in 1453. We'll use Arrian just as an example, but keep in mind this goes for the other four, as well.

Supposedly the original Anabasis was written down sometime in the reign of the Roman emperor Hadrian, about 140-150 ACE. As we discussed, there's no "first editions", hardly surprising for a thing written on fragile papyrus or parchment some 1,800 years ago.

So far as I can tell, all the extant copies of Arrian derived from a (presumably monkish) manuscript copy that was written down some time in the 12th or early 13th Century ACE.

The reason we know that all the copies originate either from this manuscript - usually called Copy "A" - or some now-lost direct ancestor of "A" is that they all share is what's sometimes called the "Great Lacuna" - a "lacuna" is the fancy name for a missing bit - that is supposed to have been the end of Chapter 12 in Book 7, where, as the Chinnock 1884 translation footnote says, "Here there is a gap in the manuscripts of Arrian, which probably contained an account of the flight of Harpalus, the viceroy of Babylon, with the treasures committed to his care, and also a description of the dispute between Hephaestion and Eumenes. See Photius (codex 92)."

I can't track down any further of the critical details such as provenance of the "A' manuscript but that it's a codex - a book-form (as opposed to a scroll) manuscript - referred to as the Codex Vindobonensis now located in the Verlag der Osterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Vienna.

Apparently at some time in the 14th Century the original text of "A" was altered. I cannot find a side-by-side comparison, but we know portions of the text were changed. Kosmin (2014) says that "A" is "...badly faded from damp. A fourteenth-century scribe (A2) carelessly rewrote over the old traces, with the result that several glosses have been absorbed into the text and the wrong case endings are used."

The manuscript of "A" is reported to have been badly damaged over time beyond just "faded from damp"; The Loeb translation (Brunt 1976) says of the 14th Century damage that the hacker who wrote over the original "Worse still, he tore out twenty pages, which were presumably hardest to read, and substituted his own, presumably bad, copy."

The 1929 Robson translation says of it that "A has gaps owing to the loss or damage of pages..." and notes that a reading of "A" should be supplemented with one of the other two "A" copies ("B" or "C") to provide as complete an understanding of the original text as possible.

We know where the differences between "A" and "A2" are because while there are only three other extent early copies of the Anabasis, two of the three are different from the third;

- Copy "B" is located in Paris, presumably at the Bibliothèque nationale de France. This 15th Century copy does not have the "A2" changes and so is presumed to have been made from "A", or another no-longer-extant copy of "A" produced before the 14th Century alterations.

- Copy "C" is reported as still in Istanbul/Constantinople, presumably either copied there in the 15th Century or brought there some time afterwards. It, too, is a copy of "A", identical or closely matching "B".

- Copy "k" is in the Laurentian Library in Florence. This version is not dated but is the only early copy that preserves the fuckups of our 14th Century hack, so is later than 1399 as well as useful in comparison to the other three.

From one or the other of these four early copies - either of "A" or the ur-A that preceded the Vienna copy - proceeded about a total of the 36 other manuscript copies we know were made prior to the Gutenberg revolution and the arrival of printed text.

But you get the idea. We know when Arrian was writing, and we know the difference between that and how old the oldest actual version we can actually sit down and read is...so we have something over a thousand years that we have no real idea how Arrian's work was transmitted. Did someone in 1200 ACE have an original? Unlikely. So what generation copy did he or they have? First? Third? Fifteenth? What possible errors might have crept in through all those generations?

We have no way to know.

A similar shroud surrounds much of the work of our other four authors:

Plutarch, like Arrian, was a Greek living in Roman times, although about a century earlier (from mid-1st to early 2nd Century ACE). Unlike Arrian, who got around the Roman world a good bit and worked the cursus honorum, making consul at one point, Plutarch was a homebody and a local official in his little town of Chaeronea.

Don't be kidded, though; Plutarch was not some sort of yokel. He'd been to the Big City in his day and had kicked it with the Big Names in Rome. Both were wealthy in provincial-aristo fashion, and both appear to have been widely published during their lifetimes.

Plutarch's contribution to the subject of this piece comes from his Life of Alexander in Parallel Lives (Βίοι Παράλληλοι), believed to have been written fairly late in his life, probably some time in the early 2nd Century.

Plutarch is less interested in pure history than in "character"; his schtick is to describe a famous Greek and then compare or contrast that figure with a Roman that Plutarch considered similar. His comp for Alexander was - no surprise - Julius Caesar.

Based on his text, Plutarch appears to have drawn largely from Aristobulus, but his main man is Cleitarchus, and to explain why that matters, we have to stop for a moment and talk about the earlier author.

If we don't know a lot about a lot of this stuff we know even less about Cleitarchus (or Clitarchus, though his name in Greek was Κλείταρχος so the former is correct). He lived in Alexandria some time in the mid to late 4th Century BCE and published a book, Perì Aléxandron historíai, (History of Alexander) at the very end of the century.

It was what we'd call today a "runaway best-seller"; everybody luuuuurved them some Cleitarchus, and his stuff sold like hotcakes...largely because Cleitarchus never let actual history get in the way of a good story.

The Wiki entry on the History of Alexander does a good job of summing up everything good and bad about the work:

"...it was the most popular work depicting Alexander in its time, but is valuable today for its unique perspective on the conqueror, in particular his psychological disposition and specifics of how the soldiers under him lived. Unfortunately, it is considered an unreliable source, with modern scholars considering Cleitarchus to have been more dedicated to writing an entertaining story than a reliable historical account."

And not just modern scholars. Arrian is supposed to have written his account in part to slap Cleitarchus around.

But, as we know from pop culture today, it doesn't have to be any good to be popular, and Cleitarchus was popular as fuck. His style was so pervasive that it even has a name; the "Vulgate Tradition". Here's from the same Wiki:

"The Vulgate Tradition itself is that of the popular narrative, typically critical of Alexander, in juxtaposition to the narratives presented in less critical accounts, such as those of Arrian. It has been criticized along with the History itself for dramatizing Alexander, focusing on the lurid details and negative aspects. Conversely, it has been commended for not whitewashing Alexander's life, and including these negative details that other historians have omitted."

This pop flavor suited Plutarch down to the ground; he didn't want to talk about boring old battles, but salacious, heroic, and intimate details of his subjects' lives.

As a result, however, his military value is not terrific, and he gives us a lot of blood and thunder but little in the way of tactical or even operational information about what happened along the river.

A textural note here, though.

The Life of Alexander is not found in the oldest manuscripts of Parallel Lives we know of; either the 10th Century parchment Codex Sangermanensis kept in the French monastery of St. Germain-des-Prés, or the 11th Century Codex Seitenstettensis in the Austrian monastery of Seitenstetten.

Not until the 13th Century does this piece of the work appear, in three parchment manuscripts now in the Bibliothèque Nationale of Paris.

Hmmm.

Diodorus Siculus is the earliest of our five heavy hitters, living in Sicily some time around the mid-1st Century BCE. His monstrous Bibliotheca historica (Βιβλιοθήκη Ἱστορική), literally "Library of History", covers the history of the Hellenic and Roman worlds from mythical beginnings down to what was supposed to be the beginning of Caesar's Gallic Wars (we don't know if it did - the last bunch of books have been lost).

The section covering Hydaspes appears to be drawn largely from Cleitarchus and Hieronymus of Cardia. It's old, yes, but it also lacks much of the detail we find in Arrian so doesn't seem to benefit from proximity to the events it recounts.

The oldest known copies of the Bibliotheca date from around the 11th and 12th Centuries; the latter in a codex in the Vatican, the former and earliest in one of the Vienna codices.

Quintus Curtius Rufus, a Roman writing in the 1st Century ACE, produced a bookshelf-filling biography of Alexander called the Historiae Alexandri Magni in Latin; of the original ten volumes we have eight.

The text suggests that Rufus, too, was in the "Vulgate" tradition and was using mostly Cleitarchus, although some of his prose seems to echo Timagenes or Ptolemy.

His Wiki entry describes his work as "...fluidly written, but reveals ignorance of geography, chronology, and technical military knowledge, focusing instead on the character." That said, Rufus includes some bits of military incunabula that seem to be original to him. Whether these were from some otherwise unappreciated primary source, or whether Rufus just made them up, is impossible to determine.

The final author that is often included is Marcus Junianus Justinus Frontinus, a 2nd (or, possibly, 4th) Century Roman author whose Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus is actually not an original work but a sort of Reader's Digest version of an earlier history written by the name-checked Trogus.

Justin, as he's usually called, gives us pretty bare bones. Here's the entirety of his account of what happened along the river Jhelum in may, 326:

"There was one of the kings of India, named Porus, equally distinguished for strength of body and vigour of mind, who, hearing of the fame of Alexander, had been for some time before preparing for war against his arrival. Coming to battle with him, accordingly, he directed his soldiers to attack the rest of the Macedonians, but desired that their king should be reserved as an antagonist for himself. Nor did Alexander decline the contest; but his horse being wounded in the first shock, he fell headlong to the ground, and was saved by his guards gathering round him. Porus, covered with a number of wounds, was made prisoner, and was so grieved at being defeated, that when his life was granted him by the enemy, he would neither take food nor suffer his wounds to be dressed, and was scarcely at last prevailed upon to consent to live. Alexander, from respect to his valour, sent him back in safety to his kingdom." (Justin, Book XII, Section 8)

Not much there, eh? Yeah, well, with these ancient authors you kind of have to take what you can get. Apparently the reason that Justin appears in this crowd is, like Plutarch, popularity. Burstein (1999) explains what was so terrific and at the same time insanely frustrating about the guy:

"Justin’s account of Alexander is not without interest. It is the earliest extant complete Latin biography of Alexander, and one of the principal witnesses to the vulgate tradition concerning the Macedonian king. Together with Julius Valerius’ Latin version of the Alexander Romance, Justin provided Medieval Europe with most of its knowledge of the reign of the Macedonian king.

The principal value of Justin’s account, therefore, is that it serves as a control on the other witnesses to the Alexander Vulgate: Book 17 of Diodorus’ Library of History and Quintus Curtius Rufus’ History of Alexander the Great. Justin’s evidence, however, is rarely straightforward. In the process of reducing the forty-four books of Trogus’ great history to the size of an average Teubner volume, Justin often misunderstood or garbled his source, omitting, combining, or misdating important historical events and characters."

So that's Justin, and the last of our primary sources.

Now we're off with the Greeks to the Mysterious East.

The Campaign: "Alexander the Great conquers the World" has been a historical trope for so long that it seems almost embarrassing to ask "why".

But if you stop and think about it for a moment, the notion of a bunch of Greek hillbillies dragging a gang of Persian nobles, Afghan tribesmen, riders from the steppes of south-central Asia, goatherders from Crete, Athenian mercenaries, and the local elephant-drivers down to the banks of a river in the Punjab region of an immense subcontinent that lay thousands of miles beyond the river is more than a little crazy.

So why was the imperial army along the banks of the Hydaspes?

Perhaps the best, as well as the shortest, answer is probably "Because Alexander was who he was".

And who that was is far, far beyond the scope of this piece. Entire libraries have been written about the man who stepped out past his father Philip's Peloponnese ambitions to bestride the Eurasian world like a colossus. All I can do is repeat everything that's been written and said: Alexander was a man of towering political and military skills, driven by daemons of ambition and power, restless, curious, physically tough, charismatic, relentless.

The reason there was a fight between the Punjabis and foreign invaders in the spring of 326 is largely because one Macedonian man wanted one and convinced tens of thousands of others to give him one.

Which is the reverse of the Alexander drachm; in only thirteen years this man's ambition changed huge parts of the world with blood and fire. His coin was foreign invasion with all that implies; war, suffering and pain, hunger and thirst, slavery and subjugation, people driven out, homeless and landless. Killing and maiming of soldiers and by soldiers of civilians.

Towns burning. Fields fallow. Widows. Orphans. The dying and the dead.

That, too, was Alexander.

But beyond the larger question, the proximal cause of the 326 invasion was the fall of Achaemenid Persia about three years earlier.

And why Persia? Well, again, Alexander. But also because there had been bad blood between Greeks and Persians since the wars of the 5th Century, and because once he'd used his New Model Macedonian Army to conquer the rest of Greece Alexander needed a cause to keep all his Greeks headed the same direction. Persia made the perfect direction; rich and an old adversary, the Achaemenids would provide loot for his troops, fiefdoms for his officers, and glory for everybody.

And so it did.

And, with it, came the eastern provinces of Sattagydia (𐎰𐎫𐎦𐎢𐏁, Thataguš), Gandara (𐎥𐎭𐎠𐎼, Gadāra) and Indus (or Sind or Hind; 𐏃𐎡𐎯𐎢𐏁, Hidūš)

The valley of the Indus had been the frontier of the Persian empire for the previous couple of hundred years, although as best I can understand the area was largely left to itself. None of the Alexandrine sources mention anything suggestive of an Achaemenid presence once east of what is now Afghanistan.From what I can tell, the expedition was driven as much by pure inertia as anything else. The Macedonian invaders had pursued Darius III east after the fall of the Achaemenid capital of Persepolis. They ran the king to ground in the eastern province of Bactria - Afghanistan - then chased down the Bactrian satrap who claimed to be the next king of Persia, and from there continued on into the mountains to the east.

None of the chroniclers seem to even stop for a moment and consider the point of crossing the Indus into what was then a vast and nearly unknown land.

The place was there, it hadn't been invaded, so it came next. That was all, and that was enough.

The Approach March: Indus to Hydaspes

One thing I enjoy about Arrian is that he's unlike many other ancient historians in willing to say straight out what he doesn't know instead of just making something up.

Another is that he has military good sense; he understands what is militarily difficult and what isn't.

Both of these show up when Alexander has to get across the Indus River into India.

"The Indus..." Arrian says "...is the largest of all the rivers in Asia and Europe, except the Ganges...(i)ndeed Ctesias says (if any one thinks his evidence to be depended upon), that where the Indus is narrowest, its banks are forty stades apart; where it is broadest, 100 stades; and most of it is the mean between these breadths."

The Indus, even without an active enemy on the other side, presented a serious military obstacle and the process of crossing was something a professional army would train to do. But how the army would train depended on the army and the trainers, and Arrian knew those could be very different.

He says that his usual primary sources are silent on the means and methods, but that he thinks it's more likely to have been what we'd call a pontoon bridge - made of rafts or boats lashed together - rather than a fixed bridge because of the short time it took to construct.

After describing the pontoon bridge method, Arrian says; "How Alexander laid a bridge over the river Indus I cannot say, because those who served in his army have said nothing about it. But I should think that the bridge was made as near as possible as I have described..."

The imperial army reformed on the southeast side of the Indus - presumably leaving a bridge-guard to secure their line of supply back to their logistical bases back in Persia - and prepare to march to the next river obstacle.

Before we get there, though, we have our first discrepancy in the source accounts.

Diodorus Siculus says that the imperials "...experienced a startling fright and relief."

"Taxiles, the king, had died, and his son Mophis had succeeded to the throne. He had sent word to Alexander earlier when he was in Sogdiana, promising to join him in a campaign against his enemies among the Indians, and now he stated through his messengers that he turned his kingdom over to him.

When Alexander was still forty furlongs off, Mophis deployed his force as if for war and marched forward, his elephants gaily caparisoned, surrounded by his Friends. Alexander saw a great army in warlike array approaching and concluded at once that the Indian's promises were made in order to deceive him, so that the Macedonians might be attacked before they had time to prepare themselves. He ordered the trumpeters to sound the call to arms, and when the soldiers had found their battle stations, marched against the Indians.

Mophis saw the excited activity of the Macedonians and guessed the reason. He left his army and accompanied only by a few horsemen galloped forward, corrected the misapprehension of the Macedonians, and gave himself and his army over to the king.

Alexander, much relieved, restored his kingdom to him and thereafter held him as a friend and ally. He also changed his name to Taxiles."

Rufus tells the same story, with some additional detail, but the thing is that both these two are "Vulgate" authors, sourcing off Cleitarchus more often than not.

But Plutarch, the ultimate Vulgate guy, says nothing about this excitement. He describes Taxiles/Omphis and Alexander as just having a cheerful meet-and-greet.

And Arrian says that "When Alexander had crossed to the other side of the river Indus, he again offered sacrifice there, according to his custom. Then starting from the Indus, he arrived at Taxila, a large and prosperous city, in fact the largest of those situated between the rivers Indus and Hydaspes. He was received in a friendly manner by Taxiles, the governor of the city..."

No trumpets, no battle stations, just a road march and a nice sit-down with the locals at the end.

All the sources agree that Omphi/Mophis/Ambhi/Taxiles told Alexander that he had issues with the guy who was running the show south of the Jhelum, Porus, so that any bad cess the imperial army might bring to the Pauravians was just nuts to the lord of Taxiles.

None of our accounts tell us anything about the timeline, but it must have taken some time - days, and probably weeks - to get everyone across the Indus, march to Taxila (about 40 kilometers southeast of the river), reorganize and incorporate the Taxilans, and then march to the northwest bank of the Jhelum/Hydaspes (about 120 kilometers from Taxila).

This delay had given the Pauravians more than enough time to pull together their own forces and meet the invaders at the waters edge.

Rufus gives us a description of the scene that greeted the imperials: "...the size of the river that must be crossed...must have terrified the Macedonians...a deep channel which nowhere disclosed a ford, it gave the impression of a vast sea...it rushed on in a foaming torrent, and rebounding billows..."

Okay, well, the monsoon is supposed to have started and the river must have been high, but...

...looking at the modern river valley I think Rufus might have been listening to war stories.

If the river may not have been the giant wave from the Perfect Storm the enemy certainly seems to have been pretty scary. Here's Rufus again:

"...the bank...had been filled with horses and men. There stood huge masses of vast bodies, and when they were purpously irritated they (that is, the Pauravian elephants) wearied the ears with their hideous trumpeting."

But the guy leading the mob on the other side of this hideous trumpeting wasn't just any old guy.

He was Alexander and he was gonna get famous or die tryin'.

The Engagement: The U.S. Army's Field Manual 90-13, River Crossing Operations, begins by telling us:

"A river crossing is a unique operation. It requires specific procedures for success because the water obstacle prevents normal ground maneuver. It also requires detailed planning and control measures and different technical support than other tactical operations require. The nature and size of the obstacle, the enemy situation, and available crossing assets limit the tactical commander's options."

Keep in mind that the author of this passage was writing for a modern military audience who would expect the commander's options to include the sort of additional combat power a mechanized armed force would expect to have on hand to disrupt an organized defense on the far bank of the river; internal fire support assets such as mortars, external fire support such as direct support or general support artillery, and possibly even more firepower all the way up to tactical air support.

And that's not even considering combat support and service elements available to support the crossing, things like assault boats or bridges (provided by engineer units) and smoke generators (operated by chemical units).

Even with all this help, though, our anonymous author of River Crossing Operations reminds us that;

"The tactical commander cannot effectively fight his force while it is split by a river. He must reduce this vulnerability by decreasing his force's exposure time. The best method is to cross rivers in stride as a continuation of the tactical operation, whether in the offense or retrograde. Only as a last resort should the force pause to build up combat power or crossing means before crossing"

Alexander's problem at the Hydaspes was that:

1. He didn't have mortars, artillery, or tac air to hammer the far bank, and

2. Porus had already beaten him to the far bank, so the "cross rivers in stride" horse was already out of the barn and way the fuck down the road.

Without the ability to shoot his troops across, Alexander had to come up with a way to deceive Porus about where and when the imperial troops were going to come over the river and then figure out a way to get over the river.

Preparations

Crossing a river the size of the Jhelum meant boats, and the imperial boats were back on the Indus. So Arrian tells us that

"Alexander...sent Coenus, son of Polemocrates, back to the river Indus, with instructions to cut in pieces all the vessels which he had prepared for the passage of that river, and to bring them to the river Hydaspes. Coenus cut the vessels in pieces and...(t)he sections were conveyed upon waggons, as far as the bank of the Hydaspes; and there the vessels were fixed together again, and seen as a fleet upon that river."

Not just seen, but seen all over the place; the imperial brown-water navy sailed up and down making itself visible now here and now there. Arrian adds: "...his vessels were sailing up and down the river, and skins were being filled with hay." The skins were the 4th Century version of rubber rafts or PFDs, a float that individual troops could paddle across the water.

While the imperial squids farkled about in boats, the imperial troops were set about building what a couple of thousand years later would be called a maskirovka.

Since Porus had "...all his army and his large troop of elephants...remained to guard the passage at the place where he saw Alexander had encamped and sent guards to all the other parts of the river which were easily fordable." Alexander set about to make "all the other parts" more difficult to guard.

"Dividing his army into many parts, he led some of his troops now in one direction and now in another, at one time ravaging the enemy’s country, at another looking out for a place where the river might appear easier for him to ford it. The rest of his troops he entrusted to his different generals, and sent them about in many directions."

Imperial HQ also did it's best to confuse the Pauravians as to the timing of the river crossing. The imperial foraging parties noisily stockpiled rations - the Chinnock (1884) translation of Arrian uses the word "corn" which was the British term for what we would call wheat, and in this case probably meant the raw materials for bread - and generally set about the rumor that the invaders planned to wait until summer drought lowered the river levels and opened additional fords.

While the intel and supply weenies were doing their best to confuse Porus' guys Alexander was busy training the Pauravians to fool themselves.

His gimmick involved marching his cavalry around making noise - "...making a clamour and raising the battle-cry in honour of Enyalius." is how Arrian describes it - and generally sounding like a bunch of horse soldiers ready to charge across a river at any moment.

Unsuprisingly, the Pauravian blocking force followed this noisy bunch up and down the river, just in case.

But that wasn't what they were being trained to do.

No. Instead, all that noise and commotion never seemed to mean anything. The Macedonians never so much as feinted at crossing. Time after time all the Pauravians just wore themselves out for nothing.

Any GI can tell you how irritating that is; you've just finally managed to get back to the bivouac site, wake up the cooks and scrounge something semi-cold out of the mess, laid out your bedroll and wriggled a comfortable spot in the dirt when some asshole comes thundering along kicking bodies and rattling something noisy shouting "stand to, move out in fifteen minutes!".

You stumble around in the dark trying to find your kit, and then stumble around some more trying to figure out who's in charge and where they want you to be or go. And then stumble along in march order, falling asleep when you stop, breaking contact before you wake and shuffling more quickly than is safe in the dark to catch up, until the whole thing straggles to an end and you end up back in bivouac trying to find a semi-quiet place to lay down for as long as you can before the asshole comes back.

After a while you just say "fuck it".

Or, as Arrian describes it:

"But when this occurred frequently, and there was merely a clamour and a raising of the battle-cry, Porus no longer continued to move about to meet the expected advance of the cavalry; but perceiving that his fear had been groundless, he kept his position in the camp. When Alexander had brought it about that the mind of Porus no longer entertained any fear of his nocturnal attempts, he devised the following stratagem."

The River Crossing

One of the reasons that the present-day town of Jhelum is commonly identified as the location of this engagement is because of the shape of the river there. Arrian says that Alexander's river crossing operation depended on a large, dramatic meander bend in the river that Arrian says was about 27 kilometers (150 stades) from the main imperial camp.

Now I'm not entirely sure that I believe that the course of the Jhelum has remained relatively unchanged over something like 2,300 years. But that IS a pretty large meander, which suggests that there's likely some sort of geologic control there, and that it's possible that the course of the river may have not grossly meandered since 326.

"There was in the bank of the Hydaspes, a projecting headland, where the river makes a remarkable bend. It was densely covered by a grove, containing all sorts of trees; and over against it in the river was an island full of trees and without a foot-track, on account of its being uninhabited. Perceiving that this island was right in front of the headland, and that both the spots were woody and adapted to conceal his attempt to cross the river, he resolved to convey his army over at this place." (Arrian V. 12)

Before we go on, one thing about Arrian's account of this plan seems weird to me.

We know the imperials started from Taxila; all the accounts mention that.

We also know that there was a main road through what is now northwest India and northeast Pakistan, what is today called the "Grand Trunk Road", that was formalized by the Mauryian Empire in the 3rd Century BCE as the "Uttarapath" (or Uttarapatha"), the Northern Highroad.

Armies, formed armies, use roads. A conventional army had nothing to gain and everything (time, effort, morale) to lose from bushwhacking through the cuna grass. It's pretty much a no-brainer that Alexander's force would have taken the Uttarapatha southeast from Taxila.

That puts them along the Jhelum/Hydaspes at modern Jhelum where the Uttarapatha crosses the river and there was probably either a big ford or a ferry (if there'd been a bridge surely one of the sources would have mentioned it, so, no) there in 326, which is why Porus was already there when Al and his goombas arrived - that's where you crossed the Hydaspes.

But if you measure the distance from the closest point on the "remarkable bend" in the river about 150 stades (given about 180 meters to the stade, so 17 miles or 27 klicks) you end up with this:

That seems weird to me.

There would be no point in shuffling the whole army sideways 10 or 12 klicks to the southwest. The Uttarapatha would have been the imperial Main Supply Route; all Al's communications back to his new empire in Persia (and from there, Macedon...) and even his local base of support in Taxila ran through there. It totally makes more sense to camp along the road.

So I think:

1) The actual crossing point was further up the river, or

2) The actual location for the main camp WAS to the southwest of the road, for tactical reasons, or

3) Arrian's distance is wrong and the camp was near the road and the crossing was closer than 150 stade.

I'm not sure why Arrian (or more likely Ptolemy) would throw in a number and get the number wrong, so my guess is it was #1 or #2, but which I have no idea. I think #1, but that's just me.

Whichever it was, what's kind of interesting is to see the various interpretations of this maneuver shown on the battlemaps you find on the Internet. Here's the version produced by the USMA at West Point:

Note there's no Uttarapatha; the battle is just kind of out in the middle of nowhere. But the big meander bend is there, at least, although there's something kind of weird about the islands, which we'll get back to.

Here's another map, this one from an article in a wargaming magazine from 2005 reproduced here.

This one's just fucking delusional, frankly; also out in buttfuck nowhere but doesn't even have the big bend in the river. Seriously? Okay, that's one's just wrong.

The best map I've seen shows all the most likely military probabilities. I've seen it in several places, but the most interesting one is in this piece in a Pakistani weekly called the Friday Times.

It has the Uttarapatha and Craterus and his holding force where it should be. It puts the crossing way the hell up the river (it's shown as 17 klicks northwest but the near end of that measurement looks like about 10 klicks upriver to the northeast from Craterus, so we're in the ballpark) which makes sense if you're trying to get around the Pauravian observation/listening posts.

The fun part of the linked article in the Friday Times, though, is that the author, a Pakistani general officer by the name of Syed Ali Hamid, posits that the engagement as conventionally described never happened - that the river in spate would have scattered the imperial force attempting to cross, and that:

"With his army scattered along the river bank Alexander would hardly have been in a position to give battle and would have sued for peace. In the legend having won a great victory, he magnanimously returns the kingdom to Porus. This was propaganda to retain support back in Macedonia by transmitting back news of great victories."Well...it's an interesting theory.

For the moment, though, we'll stick to the conventional narrative.

According to Arrian, this meant that Craterus' force and the "screen" - however that was organized - were left with instructions to hold in place unless and until they saw the Pauravian force move off (presumably to meet the imperial maneuver element); then they could cross. Then Alexander...

"...picked the select body-guard called the Companions, as well as the cavalry regiments of Hephaestion, Perdiccas, and Demetrius, the cavalry from Bactria, Sogdiana, and Scythia, and the Daan horse-archers; and from the phalanx of infantry the shield-bearing guards, the brigades of Clitus and Coenus, with the archers and Agrianians, and made a secret march, keeping far away from the bank of the river, in order not to be seen...the skins were filled in the night with the hay which had been procured long before, and they were tightly stitched up.

In the night a furious storm of rain occurred, by which his preparations and attempt to cross were rendered still more unobserved, since the noise of the thunder and the storm drowned with its din the clatter of the weapons and the noise which arose from the orders given by the officers.

Most of the vessels, the thirty-oared galleys included with the rest, had been cut in pieces by his order and conveyed to this place, where they had been fixed together again and hidden in the wood.

At the approach of daylight, both the wind and the rain calmed down; and the rest of the army went over opposite the island, the cavalry mounting upon the skins, and as many of the foot soldiers as the boats would receive getting into them. They went so secretly that they were not observed by the sentinels posted by Porus, before they had already got beyond the island and were only a little way from the other bank."

Mind you, as some famous guy said about warfare, everything is very simple but the simplest things are really fucking difficult.

In this case, it turned out that the point Alexander had picked to cross wasn't the far bank of the river. Instead it was an island, what us geomorphologists would call an "in-stream bar". A modern army would have had aerial reconnaissance or satellite photos to have picked this up, and even back in the day you'd think that the imperials would have sent a handful of recon troopers across to mark the route (and suss out any Pauravian LP/OPs - had Porus sent some guys that far upstream things might have gone pretty badly for Alexander. Actually, I think he did set some of his LP/OPs that far up, which we'll discuss in a bit).

For whatever reason - my guess is that it comes back to the reported character of the imperial commander as "impatient"; Alexander supposedly wasn't long on sitting around thinking deeply about tactics but was a sort of "make it up as we go along" kind of guy once the troops moved out - that hadn't happened, and instead the imperials found themselves separated from the far bank by "...a part of the river where the water was shallow." says Arrian. He adds that "However, the furious storm of rain, which lasted the greater part of the night, had swelled the water so much that his cavalry could not find out the ford."

Eventually the cavalry does find the ford and Alexander and his maneuver force struggle across to the far bank. There Alexander reorganizes his force.

We're not told why he did this (and several of the sources don't say anything about it at all - Rufus, for example, goes right from the crossing to the fight, saying that Alexander just "ordered his soldiers to arm themselves and take their places in the ranks") but Arrian tells us that he pulled his cavalry out to lead off, leaving the infantry to follow "at a slow pace and in regular order" (implying that the rough crossing had shaken the grunts?).

Here's my guess, though.

Almost as soon as the imperials move out they meet Kidforce. In fact, Arrian says that Aristobulus reports an even more rapid arrival of the Pauravians: "Aristobulus says that the son of Porus arrived with about sixty chariots, before Alexander made his later passage from the large island..." and that things might have gotten ugly had not Kid's guys been in too big a hurry and passed the imperial bridgehead completely.

Arrian thinks Aristobulus is full of shit, though:

"But Ptolemy, son of Lagus, with whom I agree, gives a different account. Ptolemy says that the son of Porus arrived at the head of 2000 cavalry and 120 chariots; but that Alexander had already made even the last passage from the island before he appeared."

Remember that Alexander hadn't sent across a far-security team, or done much of anything to recon the far bank before going across ash-and-trash. I think that Porus did have some people that far up the river.

Not many, not enough to actually hold the imperials at the water's edge, but that the Pauravian OP saw the imperials coming across, was seen in turn by the first of the imperial scouts, and was also seen tear-assing downstream to warn the Pauravian force that it was two if by sea and the Greeks were coming.

That meant that the imperials needed to get their asses in gear.

The Initial Engagement

Again, there's some disagreement among the sources about the actual fighting.

Several authors, including Diodorus and Rufus, don't break the actual engagement into sections. The imperials cross the river and Porus and the Pauravians tie into them, boom. They do provide details of the fight itself, but don't break it down into more than one general engagement. Rufus does mention an initial combat between the imperials and a Pauravian chariot-and-cavalry force, but says that "Already the battle had begun everywhere...", suggesting that this was just the first part of Porus' army to meet the imperial maneuver element.

Plutarch and Arrian, however, are among the sources that tell us that the fight had two parts to it, a separate initial encounter between Alexander's vanguard and some part of the Pauravian force led by someone other than Porus - Arrian says it was Kid, Plutarch doesn't give us anyone - that was distinct from the main encounter.

Whichever it was, the initial meeting engagement between Pauravians and imperials is described as pretty one-sided.

Arrian says that Alexander "...immediately made a rapid charge upon them with the cavalry around him. When they perceived that Alexander himself and the body of cavalry around him had made the assault, not in line of battle regularly formed, but by squadrons, they gave way; and 400 of their cavalry, including the son of Porus, fell in the contest. The chariots also were captured, horses and all, being heavy and slow in the retreat, and useless in the action itself on account of the clayey ground."

Plutarch doesn't give the detail about the imperial cavalry piling in right off the line of march but agrees that "...after routing a thousand of the enemy's horsemen and sixty of their chariots which engaged him, he captured all the chariots, and slew four hundred of the horsemen."

Both Diodorus and Rufus agree that the imperial cavalry did for the Pauravian chariotry, with Rufus adding the detail that Arrian notes about how the ground was trouble for the chariots: "...the chariots sent over the slippery and impassable ground shook off those who guided them." by which I think he means that the drivers and crew - "those who guided them" - were thrown off the fighting platforms when the chariots slewed or overturned.

A Brief Discursion About Indian (and other) War Chariots

One thing I want to mention here is the difference between these things as they're mentioned here and what you might be thinking of when you think "chariot".

The televison-and-movie-default image of a chariot used in warfare is the Egyptian variety; a light, fast, two (or even one) person vehicle drawn by a single or a pair of horses. Yul Brynner and his gang as the Bad Guys in The Ten Commandments, right?

This was NOT what we think a Pauravian chariot looked like.

Rufus says that Porus' chariots carried six guys: "...two with bucklers (shields), two archers stationed on each side, the rest were the drivers, who...when it was necessary to fight hand-to-hand...dropped the reins and poured a shower of javelins upon the enemy."

A battlewagon carrying six troops and all their weapons and kit would NOT have looked anything like those zippy pharonic sports cars, but more like this:

The two versions of "combat car" did have one thing in common, though.

They were both put out of business by true horse cavalry.

The chariot was a solution in search of a problem that had already been solved by forking the hayburner rather than hitching it to a truck.

A person on a horse had all the same advantages - height and speed - with none of the disadvantages of vulnerability to rough or boggy terrain and poor manuverability the chariot had.

Pretty much every time chariotry encountered cavalry the truck-drivers got handed their ass, which is why in the constantly-fighting polities around the Mediterranean the chariot disappears from the order of battle before the 5th or 6th Century BCE, and from China about the same time.

Porus' chariotry seems to have been something of a relict, and they received the same rough treatment that obsolete equipment usually gets in warfare, unfortunately for the troops assigned to them.

So far, so bad for the chariot boys and the defenders in general. Let's get back to the action, then.

(We'll talk about these elephants in a bit; suffice to say this isn't what they looked like...)The Main Engagement

We've figured that the Pauravians weren't caught entirely napping by Alexander's river crossing. Their picket alerted Porus, who sent Kidforce out to delay the invaders while he trundled the bulk of his force east to meet them in force.

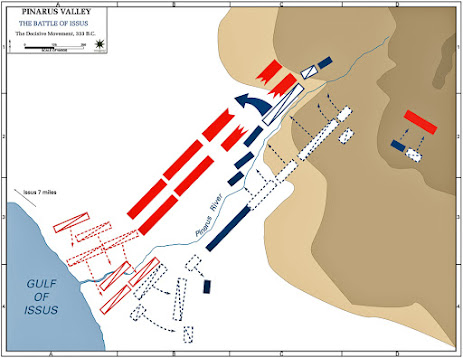

Arrian, again, gives us the most detail of how that force turned out against the imperial maneuver element:

"First he placed the elephants in the front, each animal being not less than a plethrum (about 100 feet) apart, so that they might be extended in the front before the whole of the phalanx of infantry, and produce terror everywhere among Alexander’s cavalry. Near these he had posted the infantry, not occupying a line on a level with the beasts, but in a second line behind them...He had also bodies of infantry standing beyond the elephants on the wings; and on both sides of the infantry he had posted the cavalry, in front of which were placed the chariots on both wings of his army."

Pretty straightforward; ground-holding elements - infantry and elephantry - in the center, mobile elements - cavalry and chariotry - on the flanks to prevent getting enveloped.

The imperials, on the other hand, had a very particular arrangement that went all the way back to Philip of Macedon's army that depended hugely on "precedence"; the right of position based on seniority and the scale of "eliteness" in the tribes of Macedon. Arrian again:

"Against the (Pauravian) right wing he (Alexander) sent Coenus with his own regiment of cavalry and that of Demetrius...Seleucus, Antigenes, and Tauron were ordered to lead the phalanx of infantry, but not to engage in the action until they observed the enemy’s cavalry and phalanx of infantry thrown into disorder by the cavalry under his own command...he launched the horse-archers, 1000 in number, against the left wing of the Indians, in order to throw those of the enemy who were posted there into confusion by the incessant storm of arrows and by the charge of the horses. He himself with the Companion cavalry marched along rapidly against the left wing of the barbarians..."

In Macedonian war the right side of the line was the "post of honor". So if you were, say, the imperial guard infantry - here the Hypaspists, or if they were present the "Silver Shield" inner-guard division of the guard - you were always the right-hand infantry unit. The cavalry was more elite than you, though, so outside the right end of the infantry line you'd find the cavalry units, with the "Agema", the guard cavalry, as the far right-hand cavalry unit, and so it was at the Hydaspes.

The remainder of the main line would be the various taxeis of the phalanx, with more heavy cavalry on the left. The very outer fringes of the line (and probably in front, as a screen and skirmish line) would be a mix of archers and peltast light infantry. Here's an example of a "typical" Macedonian formation:

The thing we tend to forget, because he was a "military genius", is that Alexander was sort of a one-trick tactical pony. He was pretty incredible at getting his forces around south-central Eurasia in a way no military force before or until the Mongols afterwards figured out.

But once he got them to the fight, he did pretty much the same thing every time; he'd use his big pike-blocks to lock down his enemy, and then he'd swing his heavy cavalry into them and smash them apart.

Think I'm kidding? Here's his first "big victory", Granicus in May 334 BCE:

There's some dispute about this; Arrian says that the two armies were separated by the Granicus River. Ffirst Ptolemy's cavalry crossed and hit the Persian right, but that once that side was reinforced and Ptolemy driven back, the whole Macedonian force swarmed across the river led by Alexander's Companion cavalry wedge which broke into the Persian cavalry line, killed a bunch of their nobles, and the Persians just blew away.

Diodorus says the river crossing came first and was unopposed. Nobody has ever been able to reconcile the two, so we're not sure exactly what happened.

But, regardless, the basic pattern starts here; Macedonian cavalry rides down an enemy force that has to stay spread out and fixed in place unable to respond because of the danger of the phalanx.

Next up, Issus, in November 333.

This time the first blood is drawn by the Persian right wing cavalry, that crosses the river and hammers the Macedonian and allied cavalry. The left-wing commander, Parmenion, holds long enough for the phalanx to bull it's way into the Persian (and largely Greek mercenary) center so Alexander can lead the Companions directly at the Persian king. Darius grabs a hat, his people have no interest in dying for his pusilanimous ass, and the Persian army falls apart.

Last? Gaugemela, October 331.

No rivers here, and Alexander does get kind of tricky; he refuses both flanks and tempts the Persian cavalry to try to Cannae him.That doesn't work; Parmenion on the left, again, fights the Persians to a standstill, Alexander does the same on the right, and while the Persians are hammering away along the line Al starts disengaging his Companion cavalry and as many infantry as he can find, and then...

...boom. Yep, you guessed it; Campanion cavalry hey-diddle-diddle-straight-up-the-middle.Al had his opposite number Darius pegged by this time; come after him and he's outta there. Darius bugs out, his army falls apart (except of the right, where Parmenion is catching hell and Al has to turn back to rescue him) and it's all over but the butchering-the-helpless-screaming-fugitives fun part.

See the pattern?

Okay, so no huge surprise to see this again in India.

Horse Archers vs Chariots, Cavalry vs Cavalry

Remember what Arrian said; the thousand or so Dahae light horse archers take the first lick, against the Pauravian left-flank. The chariotry there is the lead element, and the result was pretty much what you'd think when hoarse nomads are loose against battle wagons. Rufus says that:

"The frightened horses...dragged the chariots not only into the mudholes and pools but even into the river...Porus...saw the chariots wandering all over the field without drivers."

Galled by this bowfire and the decimation of the chariotry, Porus' left-flank cavalry pushed up either to support the chariots, drive off the Dahae, or both. They are supported by the right-flank cavalry, which Porus shifts all the way around his line.

At this point the imperial cavalry smashes into the Pauravian left.

This is a very peculiar move for both sides.

First, I'm not sure why Porus sends all his cavalry to his left. It uncovers the right end of his infantry line, unless he thinks his right-flank chariotry is going to do better than, well, any of his chariots have done up to this point. It's invaders 2, fucking chariots nothing at the end of the first period.