Author's Note: I first wrote up this engagement waaaaay back in 2008; it was only the second "decisive battle" piece I ever wrote for this blog. Recently I took a look back and was pretty appalled at how slipshod I was back in those days, and decided that - given the historical importance of the event - I should rewrite and upgrade it. I missed the April date because Bay of Pigs ate my brain, but here it is, a month late but new and improvedTM from the original.

First Panipat ("The First Battle of Panipat") Date - 21 April, 1526 CE (932 AH)

Forces Engaged: Mughal:We'll get to this in

Sources, but we don't have a breakdown of the Mughal army that advanced to the "City of Weavers" in the spring of 1526 of the Christian Era. As discussed below, the "Mughal" empire (and the people who would have marched with Babur wouldn't even have called themselves that; their name for themselves was

گورکانیان,

Gūrkāniyān, "sons-in-law", and the contemporary term most commonly used for the dynasty they established was "Timurid" derived from the Turkic/Mongol ruler Timur who had set it up in the 14th Century CE) was a polyglot organization formed from what are now several Central Asian states.

We don't have any detailed breakdown of the Mughal force that met the Delhi forces at Panipat, so the best we can do is infer backwards from Mughal forces we do know something about, the Mughal armies of Akbar I, Akbar the Great, in the late 16th and early 17th Centuries CE.

Cavalry

These armies were largely composed of cavalrymen.

Horse soldier numbers as high as 250,000 have been estimated for later Mughal armies of this period. (Sarkar, 1912), in a force of 400,000 all arms, estimated as many as 350,000 cavalry for Shah Jahan's army of the 17th Century CE, but the general consensus that Babur's force was nowhere near that size.

The Mughal forces evolved from, as we've noted, the Timurids, who had, in turn, evolved from a mashup of Mongol armies that had conquered their way into what is not eastern Turkey and Iran - Persia, at that time - and had adopted a lot of the military methods of those societies.

So while the Mughal cavalry was still, like the Mongol army we discussed at Ain Jalut, composed of a mixture of mounted archers and heavy shock cavalry, the horse bowmen had changed a lot.

The Persian cataphract cavalry that the Mongols had encountered back in the 14th and 15th Centuries CE had been a nasty surprise for the riders off the steppe. While slowed by their armor they were unpleasantly proficient with the bow, and could back it up with a lance and sword or axe if they got close enough.

So the Timurids did the sensible thing; they adopted the cataphract techniques and added them to the Mongol tactical flexibility that had helped them beat the Persians.

Our best guess, then, is that the force Babur brought with him out of the northwest was 1) largely mounted, and 2) probably about 50/50 heavy horse archers and heavy shock cavalry.

Why don't we have better numbers?

Simple; we don't have the documentation. We'll talk about that when we get to Sources.

Another thing to remember about the Mughal forces is that they were raised by a feudal society in the way most feudal armies were raised, which is to say that the "army" was a mass of individual contingents raised by and following their leaders.

So, one big reason we don't have better numbers, is when Babur describes his force at Panipat he doesn't bother describing the troops or listing their numbers, he just lists the leaders: - "Our right was Humayun, Khwaja Jahan, Sultan Muhammad Duldai...". Presumably his readers would know who followed who, so there was no need to detail the grunts. So we're left with more or less guesswork.

Infantry

The Mongol tradition had no room for footsoldiers, and Mongol experience suggested that infantry armies were dead meat for a well-organized force of arrow-firing cavalry (which was "Mongol" all over when you think aboit it...) so the lot of a ground-pounder in a Timurid and, later, Mughal army was not a happy one.

But someone had to hold rough terrain, guard the baggage train, dig siegeworks, and do all the scut work no self-respecting cavalryman would do.

So, infantry.

Presumably these would have included everything from irregular light infantry used for scouting and screening in bad cavalry country through heavy infantry used to hold ground or seize it where, again, cavalry was contraindicated. "Footsoldier" as a Mughal category also included everyone from sappers and miners to saddle- and harness-makers and cooks and bakers.

There were elements of the Mughal dismounted force who "counted", however; the artillery and the matchlock musketeers.

These were a Mughal innovation; nobody else in south Asia had gunpowder technology, not in any sort of organized fashion. But the Mughal armies had both matchlock-armed infantry - bunduqchi - and cannon gunnery ranging from light fieldpieces up to heavy and superheavy siege artillery. Obviously the field guns were the only cannon present at Panipat.

Again, we're not really sure how many of each element Babur brought to the field. The Baburnama says that 700 carts had been brought into the Mughal position and linked together - "...in the Ottoman fashion, but using ropes of rawhide instead of chains" is the way Babur describes it - with mobile wooden shields (mantlets) between them to provide a fortification for the musketeers and artillery to defend.

|

Not Mughals! This is a medieval "wagenberg" from Europe...but you get the idea

|

There must have been enough of both of these gunpowder weapons to have the effect they are described as making. So let's guess somewhere between 3,000 to 5,000 musketeers - 4 to 5 guys per cart - and maybe 20 to 30 cannon with crews of 10-20 gunners and matrosses; something like 200-600 redlegs.

I've read a fairly wide range of guess for the overall size of the Mughal force. Babur's account stresses how much larger the Delhi army was (but of course he would...) and if so the top figure can probably be half the Delhi number - 100,000 - or so. But the more typical number is well below that; closer to 25,000 or 30,000 or thereabout.

The numbers I've seen as low as 12,000-15,000 seem too small; even a technically and tactically superior force that size would have had trouble holding enough ground to keep the Delhi mob from swarming over them...but we can't rule out the possibility that Babur didn't have much more than that.

So let's guess about 15,000 cavalry - probably 7,000 armored horse archers and another 7,000 heavy armored lance- or sword-and-shield cavalry, 10,000 infantry (of which something like half to two-fifths were projectile-firing matchlockmen, the remainder largely foot archers), 20-30 light field artillery cannon, and some unknown number of elephants, camp followers, donkey carts, and Allah knows what other kind of ash-and-trash, all under the command of Shah Zahīr ud-Dīn Muhammad, better known by his nickname Babur, a Persian word meaning "tiger".

Delhi Sultanate:

Again, the only information we have about the force that marched up from Delhi to confront the invaders is from the invaders' own account. Here's all that Babur says about the Delhi forces in the Beveridge (1922) translation:

"People estimated the army opposing us at 100,000 men ; Ibrahim's elephants and those of his amirs were said to be about 1000. In his hands was the treasure of two forbears. In Hindustan, when work such as this has to be done, it is customary to pay out money to hired retainers who are known as "b:d-hindi"*** If it had occurred to Ibrahim to do this, he might have had another lak (Note: a lak or lakh is 100,000) or two of troops. God brought it right! Ibrahim could neither content his braves, nor share out his treasure. How should he content his braves when he was ruled by avarice and had a craving insatiable to pile coin on coin?"

(*** This word is explained in the translator's footnote as meaning "raider" or "plunderer", implying that these were irregular mercenary (probably cavalry) troops known for their lack of discipline)

The then-ruler of the polity based in Delhi - diminished from it's height but still one of the more powerful in North India - had come from out of what is now Afghanistan, and the Delhi armies were based on Afghan models that had been modified by residence in the North Indian plains and the varied history of the Delhi dynasties, beginning with Turkish mamluks in the 13th Century and running through several Central Asian powers, including local Muslim groups (such as Rajputs).

The Delhi military was, much like the Mughal, based on armored cavalry. The biggest difference is that Delhi armies also relied heavily on the war elephant we ran into along the banks of the Hydaspes back in November.

The cavalry would largely have been similar to the Mughal shock cavalry - neither the Mamluks nor the Afghans were primarily horse archers like the Mongol predecessors of the Mughals - and the elephants would have been remarkably similar to the Pauravian versions, only probably better armored.

Note that the elephant still doesn't have a tower or

howdah fighting platform buckled on; the crew rides the animal's back or, in the mahout's case, it's neck.

The Delhi heavy cavalry would have included Turkish/Afghan armored heavy horse who, like the Mughal "braves" would have been the fighting tails of their leaders, and a Turkish version of mamluk called غِلْمَان (ghilmān) who were slave-soldiers to the Delhi sultan. Both would have looked very similar to the Mughal heavies; scale or lamellar mail (up to and including horse armor), lance, sword (or axe) and shield.

Delhi infantry were worse off than their Mughal counterparts because the bunduqchi and the artillerymen were missing. The footsoldiers came in roughly three flavors, according to this website, the best internet source I could find for the troop types at Panipat:

Pashtun tribesmen; your basic hill bandit toting whatever edged weapon they could scrounge and as much armor as they could steal or buy.

Light foot archers; similar to the Mughals', with recurve bow and probably mail if their leaders were wealthy enough, and

Local conscript infantry

; poor schmoes dragged in by their zamindars - that is, the big landowner in their district, who held them in what amounted to servitude. Poorly armed and equipped, the north Indian equivalent of the medieval European "peasant levy" largely there for menial digging and carrying tasks, but at need might have a sword or bow shoved into their hands.

No artillery

If we're to believe Babur the whole mob came to something like ~100,000 total, but probably only about 30-40,000 effectives, almost entirely heavy shock cavalry, but also probably including rag-ends of infantry and some number between 100 and 500 war elephants, under the nominal command of Ibrahim Lodi ( ابراهیم لودي, (in Hindi इब्राहिम लोधी), 28th Sultan of Delhi.

The Sources: And here, again, as almost always with these engagements fought before widespread literacy and the printing press, we find ourselves at the mercy of the scriptorians.

The primary, and often the single, source for what we know about First Panipat is the conqueror himself, Babur, in his autobiography, known as the Bāburnāma (بابر نامہ), the "History of..." or "Letters of..." the future first Mughal Emperor.

From its content (and the translator's notes in the 1922 Beveridge edition) the original - said to be a codex; that is, a book-form manuscript rather than a scroll - was finalized - probably from notes and journals the emperor had jotted down during his earlier adventures - some time between Panipat and the emperor's death in 1530 CE (936 AH), and was set down in a script known as Chagatai (چغتای Čaġatāy), a form of Turkic that had developed from an earlier Turki variant some time between the 13th and 14th Centuries CE.

By the time of Panipat Chagatai had been the "official language" of the Timurid state and became that of the Mughal empire, as well. The Wikipedia entry cites Dale (2004) as describing Babur's Chagatai as "...highly Persianized in its sentence structure, morphology, and vocabulary." The original Bāburnāma seems to have been a combination of journal, biography, and literary work, containing the first Mughal emperor's diary as well as Persian poetry and observations on everything from natural history to politics.

I cannot find any secondary sources that have a definitive answer to the question of the exact time span over which the work was composed or who actually wrote it down; that is, whether a copy existed in the emperor's own hand or if it was dictated to imperial clerks.

Internal evidence suggests that Babur was still working on it within less than a year and a half before his death, and in the Akbarnama, the official history commissioned by Babur's grandson Abu'l-Fath Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar ( ابو الفتح جلال الدين محمد اكبر) better known as "Akbar the Great", the third Mughal emperor) the author, Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak, says; "He (Babur) also wrote his waqi’at from the beginning of his reign to the time of departure (the term used is "inteqal", meaning his death) faithfully, in a lucid and elegant style."

As we've seen before while doing these manuscript chases, though, the real troubles begin after the initial account is written.

First, the Bāburnāma as we have it today is kind of a mess. The account begins suddenly in the middle of Babur's twelfth year - "In the month of Ramadan in the year 899 (1494 CE), in the province of Ferghana, in my twelfth year I became King." No introduction, none of the usual royal and imperial lineages, suggesting that there is a whole section, or sections, missing from the beginning of the story.

Within the volume, too, there are lacunae - these are missing pieces, remember, from our discussion of Arrian's Life of Alexander - that lose huge chunks of Babur's life and reduce the actual span of his 47 years to only about eighteen years detailed by the remaining fragments..

According to his translator Beveridge (1922), these lacunae are present in every version we have of the Bāburnāma, both the copies in the original Turki which she consulted for her translations as well as all the numerous Persian translations commissioned during Akbar's time. In the Padshahnama (or Badshah Nama, پادشاهنامه or پادشاهنامه), a collection of chronicles completed in the reign of Shah Jahan during the 17th Century CE) of Abdul Hamid Lahori, the author reports that the copy of the Bāburnāma that he consulted was 1) an autographed copy that 2) mutilated in the same way as all the existing versions of his time.

What happened? It's hard to believe that Babur intended his journal to be read in such a fragmentary condition.

Beveridge (1922) provides three possible explanations for the missing pieces.

First, that the manuscript was damaged in 1512 CE (918 AH) when Babur's camp was overrun. This seems implausible; one would think that the emperor would have had time after Panipat to restore the lost sections.

A second involves a sudden storm in 1529 CE (935 AH), of which Babur writes:

"...within an instant such a storm brewed and fierce wind arose that few

were the tents that did not blow down. I was in my audience tent

writing. There was no time to gather my papers and notebooks. The wind

brought down the tent and its porch on my head. The smoke vent broke into pieces. God kept me safe, and no harm was done, but my books and papers were drenched. We gathered them together with difficulty, wrapped them

up in a woolen bedspread, and put them under the cot and spread rugs on top. After two gharis (a ghari is a Vedic time unit of about half an hout) the wind died down. We had the toshakkhana

tent (an equipment tent used for storing bedding) erected, lit a candle, and with great difficulty got a fire going

and then got busy drying out the papers and notebooks until dawn with no

sleep."

This seems more likely, close to the end of the emperor's life, although we aren't told which "books and papers" were involved, or whether they were too badly damaged to be repaired.

A third explanation, which seems to me the most likely of all, is that the original manuscript was in the possession of Babur's son and successor Nasir-ud-Din Muḥammad ( نصیرالدین محمد, typically referred to by his "imperial name", Humayun ( همایون)) when the latter was driven from power in 1542 CE (948 AH) and spent the next 14 years in Persian exile. The original was tossed into a saddlebag, or a box, shoved into a trunk or a cabinet, got wet, got scuffed, got torn...so by the time Humayun won back the Mughal throne the journal was pretty beat up.

Beveridge (1922) says that the original was still around in the early- to mid-1600s CE; "My latest definite information about Babur's autograph MS. comes from the Padshah-nama (Bib. Ind. ed. ii, 4), whose author saw it in Shah-i-jahan's private library between 1628 and 1638."

Since that time the original has disappeared.

Several copies in the original Turkic are know to exist. Here's Beveridge (1922) table listing the copies known of in her time:

Beveridge does a good job of tracing the lineages of the Turkic manuscripts. The original seems to have been copied at least twice once in 1529 CE ("Ahrar's Codex") and again around 1531 CE ("Humayun's Codex"). At least one - Humayan's - contained the full text ("unmutilated") and Beveridge infers it was copied again "between 1556 and 1567" as what is known as Elphinstone's Codex currently in the Advocate's Library in Edinburgh.

A version that is supposed to have been copied some time around 1700 CE was found in Hyderabad and brought to the attention of Annette Beveridge, a professor at the women's college in Calcutta, around the turn of the 19th Century.

It was presumably there, at Bethune College, that she translated this "Haiderabad Codex" into English and published the results between 1920 and 1922.

A ninth version is described in Erskine and Leyden (1921) as

"The Russian Foreign Office MS. Transcribed in 1757 by Dr. Kehr

from an unknown source. This manuscript…although old and therefore important, it

is not, in the opinion of Mr. A.G. Ellis (late Assistant Librarian, India Office,

whose knowledge of Oriental bibliography is unrivalled), of very great value, being

at times ungrammatical, and even unintelligible."

So to hell with those Russkies, then!

The

Beveridge translation appears to be considered one of the better Turkic-to-English versions, which also includes a 1909 translation by F.G. Talbot, and the most recent, in 1996, by Wheeler Thackston.

There's another lineage of the work, however, that begins in 1589-1590 CE (994-995 AH) with the translation of one of the "mutilated" Turkic copies into Persian. This translation was ordered by Babur's grandson, Emperor Akbar, and is reported to have produced three texts.

The 'Abdur Rahim's translation (1590 CE) is supposed to be

relatively faithful to the original, and was widely copied thereafter. These

copies apparently tended to be prettier than reliable. Erskine and Leyden

(King rev., 1921) describes one in the British Museum as “...a fine copy (Or.3714), illustrated

with exquisite miniatures by Akbar's artists, but it does not present a very correct

text."

Other Persian copies are said to include an incomplete version copied in 1586 CE, and a fragment translated by Zayn al-Dīn Wafāʼī Khwāfī in 1590 CE. Neither appear to have been significant to our story.

Mind you, the Bāburnāma isn't the only source for Panipat although it appears to be the Q-text from which all the others are derived. The same Zayn al-Dīn Wafāʼī Khwāfī that translated a portion of the original also wrote an account covering the events of 1525-1527 CE. This work is known as the Tabaqat-i Babur; "Tabaqat" is an Arabic word meaning "generations", and was a form of biography spread across a chronological group. The Tabaqat is described following the narrative of the Bāburnāma but "adding" to Babur's descriptions, presumably with what Zayn Khwāfī saw himself.

The problem for me is that there is absolutely no copy of this manuscript anywhere on the internet, and library copies tend to be in places like Tokyo and Cairo. There are English translations on sale, but they're out of stock everywhere, and the cost where you can find it is punitive. I'd love to read what Zayn Khwāfī has to add, but for a hobby historian on the internet? That's just nor practical.

As always, the other aspect of our Sources issue is that the victors wrote the history. We don't have any insight from the Lodhi camp, or are we likely to ever find any. So the picture we have, of the engagement and the campaign that led up to it, is painted by the side that won the fight. The partisans of one faction in a war seldom spend a lot of time pondering the rightness of their cause or the possible causes of their enemies. Might makes right, and so it did on the north Indian plains in the spring of 1526 CE, nine hundred and thirty-two years after the Hijira.

The Campaign:

While I'm not much of a believer in the "Great Man" theory of history,

the situation in north India in the early Sixteenth Century CE was as much

a product of the personality of

Babur as anything else.

Babur was something of Central

Asia's stormy petrel; starting out in 1483 CE as the son of a local khan of

Persianized Mongol descent in what is now Uzbekistan, Babur fought and

intrigued his way across much of central Asia for the next forty-odd years.

At fourteen he captured Samarkand and lost it within a year. By 1504 CE

he was hammering away in what is now Afghanistan and by 1511 CE, now allied with the Safavid

Persian Shah Ismail I, he had taken Bokhara and retaken Samarkand.

It

was some time in the second decade of the Sixteenth Century that the future Mughal ruler began to look south to the rich Indus plain and rub his

chin...

The

political authority in the north Gangetic plain at the time was the

so-called Delhi Sultanate. This accretion had begun as a Persian

conquest of Ghazni, Multan, Sindh, Lahore, and Delhi in the 13th Century

before inculcating Turkish, Rajput, Mongol and finally Afghan

influences.

The Sultan in 1526 was a man named Ibrahim Lodhi, third of a

family from the Gilzai tribe in Afghanistan to rule in Delhi, and - according to his Mughal opponents - not a

popular or particularly effective ruler.

He appears to have been such

putz that even his fellow Afghans preferred a foreigner to their

homeboy: they invited Babur to come take a shot at the last of the

Lodhis.

One other thing should be highlighted about the situation

in 1526 CE that we've already discussed a bit: the technical advantage the Timurids brought with them into

India. Through the Safavids, who had quickly adapted the gunpowder

weapons used against them so effectively by

the Ottoman Turks, Babur re-equipped his infantry with matchlock muskets

and augmented his army with field artillery.

This would have a critical effect on the

engagement at Panipat.

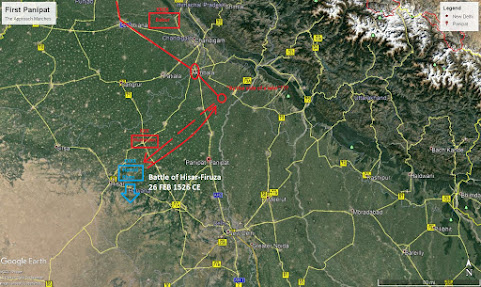

The Approach March: So Babur describes his approach march towards Panipat from the northwest as a fairly periodic progress through some nasty weather early on; he says that when in "Rupar" some time in late winter (presumably modern-day Rupnagar, about 180 kilometers north of Panipat) "...it rained very much and became so cold that a mass of starved and naked Hindustanis died."

The Timurid/Mughal force seems to have marched south and east towards Delhi. At Sirhind, about 144 kilometers north of Panipat, Babur mentions meeting with an envoy from Delhi; there's no mention of any sort of negotiations in the

Bāburnāma, so it seems fairly obvious that both sides had no interest in coming to some kind of accommodation.

The Mughal army continued moving southeast, to what is now Ambala, and from there to "the side of a lake", presumably somewhere to the south, or southeast.

At this point Babur's intel people got word that the Delhi army had marched out...but also that a separate force under one of Ibrahim Lodhi's relatives, one "Hamid Khan", had left it's marshaling area and was moving towards the Mughal forces from the southwest.

Babur dispatched his son Humayan with "the whole of the right wing" - sensible, given that Hamid Khan was advancing towards the Mughal right - who met the Delhi force in late February by Western reckoning.

Babur's account of the engagement suggests that all was not well with the Delhi troops. Humayan's force detached a small element - 100 to 150 "braves", presumably heavy cavalry - to move to contact. This recon element tied into the Delhi force (we're not told how large the Delhi army was) and was still fighting when "...after a few encounters the dark mass of Humayan's troops showed in the rear, (of the recon element) the enemy ran right away."

Humayan returned to the main Mughal camp with about 100 prisoners and a handful of war elephants.

Babur ordered his musketeers to murder the prisoners, which they did, and the Mughal army marched out of Ambala to the modern town of Sarsawa, about 70 kilometers southeast of Ambala, and about 80 kilometers north-northeast of Panipat, and from there

"...two marches along it's (the Junma River)

bank..." when intelligence arrived of yet another detached Delhi element.

"...of those sent to gather news," Babur wrote, "Haidar-quli brought word that Ibrahim has sent Daud Khan Lodhi and Hatim Khan Lodhi across the river into the Mian-du-ad (the translator uses the term "tween-waters", presumably meaning an instream bar or island between channels of the Junma) with with 5 or 6,000 men..."

Babur sent another expeditionary force to hit this detachment; he says that he sent them to "...ride light...", but for "light" Babur sent a bunch of his troops, including "...the whole of the left..." as well as several leaders from his center element and right.

This force attacked the Delhi detachment at dawn, 1 APR 1526 CE, and the fight went about the same as the earlier engagement at Hisar-Firuza.

"...our men closed with his at once, overcame them, hustled them off, pursued and unhorsed them until they were opposite Ibrahim's own camp." (which Babur had stated that was about 6 miles away, so the pursuit had extended that far). The Mughal victors captured Hatim Khan, about 60 Delhi troops, and another 6 or 7 elephants.

We're not told what happened to Hatim Khan, but the 60 other poor Delhi bastards "...were made to meet their death-doom", as Babur puts it.

Fun guy.

The Engagement: Babur says that the army halted north of what would be the battlefield to collect the carts they would use as field fortifications, and hold a final council of war. In this...

“…General Council where opinion found decision at this: Panipat

is there with its crowded houses and suburbs. It would be on one side of us;

our other sides must be protected by carts and mantelets behind which our foot

and matchlockmen would stand. With so much settled we marched forward, halted

one night on the way, and reached Panipat on Thursday the last day (29th) of

the second Jumada.” (12 APR 1526 CE)

As they had planned, the Timurid/Mughal army used the town of Panipat to anchor their right flank. The left, which was technically "in the air", was stiffened with field fortifications.

Now.

That's an awful pretty map (it's from this little website, which also gives a lot of useful information about the fight) but you need to keep in mind when you see cool tactical maps like this about ancient warfare; there was no military history section of the Mughal Empire.

What we know about this fight is what Babur (and some of his pals, like Zayn al-Dīn Wafāʼī Khwāfī) tell us, and their descriptions are nowhere this detailed. So the nice little rectangular blocks of troops, say the double line of four in the Delhi army?

That's pure conjecture, or, more realistically, pure imagination. We have no idea what the Delhi formation actually looked like, because Babur & Co. never tell us.

But it serves us as students of the "Science" of warfare to lend order to what was probably just a vulgar brawl.

Babur says that:

"On our right was the town of Pani-pat with its suburbs; in

front of us were the carts and mantelets we had prepared; on our left and elsewhere

were ditch and branch. At distances an arrow's flights sally-places were left

for from 100 to 200 horsemen."

And that's where they waited a week.

I have no idea what was going on in the Delhi headshed. If Babur's numbers are even anywhere close to right the Delhi force was immensely stronger; something between four and ten times the strength of the Mughals. With those numbers they should have been easily able to fix the Panipat defenses and turn the Mughal left. They didn't; from Babur's account the Delhi army simply sat there in front of Panipat while the invaders made nuisance raids on the Delhi camp.

"During the 7 or 8 days we lay in Panipat, our men used to

go, a few together, close up to Ibrahim's camp, rain arrows down on his massed

troops, cut off and bring in heads. Still he made no move; nor did his troops

sally out. At length, we acted on the advice of several Hindustani well-wishers

and sent out 4 or 5000 men to deliver a night-attack on his camp…"

All night operations are dicey, and it sounds like the Mughal raid was more of a clusterfuck than most. Babur says that because of the dark his guys "...were not able to act together well...", which sounds like an understatement - the raiders got lost in the night, stumbled around uselessly, and were caught by daylight right outside the Delhi lines. The Delhi troops sortied, Babur brought up reinforcements, and the whole thing just sort of petered out.

The next day, however, it was game on.

The Delhi troops were reported coming on "...advancing in fighting-array". Babur says that the attack seemed to be aimed towards his right around Panipat, so Babur shifted his right-hand reserve under Abdu'l-aziz to reinforce his right wing.

He says that when the Delhi army began to close on his defensive lines they seemed to lose their enthusiasm.

“…his pulled up and, observing our formation and array, made

as if asking, " To stand or not ? To advance or not? "

They could not

stand; nor could they make their former swift advance.”

Babur sent his left and right wings forward to envelop the Delhi advance. This is why I suspect that most of the historians who discuss this engagement speculate that, despite Babur's estimate of his enemy's numbers, the size of the force that actually reached the Mughal lines was significantly smaller than 100,000.

Whatever the size, the military value of the Delhi troops seems to have been relatively low. Babur says that rather than being dangerous the numbers of his enemies only hampered each other; "His right and left hands were massed in such a crowd that

they could neither move forward against us nor force a way for flight.”

Apparently the fighting went on for three hours or so, from when the "sun was spear-high" until about midday. The firepower of the muskets and artillery was decisive in repelling the Queen's Move of north Indian warfare, the charge of war elephants.

Without their rooks the result was predictable. By noon the panicked Dehli troops fragmented, no doubt encouraged in this by

their elephants, out of control and frantic to escape the noise and

carnage.

Somewhere in this carnage

Sultan Ibrahim was killed. The loss of the only real reason his troops were in

the field resulted in disintegration of the Delhi army.

Timurid

losses were in the low thousands, while as many as 40 to 50,000 Delhi troops

may have been killed (Babur says that his guys counted about 15,000 dead on the ground, but heard the higher number "from the statements of Hundustanis").

Babur was in Agra and Delhi within the week. The

Mughal Empire had begun - the Islamic dynasty that would rule most of

India until the coming of the British two hundred years later.

The Outcome: Grand strategic Mughal Victory, with geopolitical consequences.

The Impact:

In the short run, Panipat (and the consolidation that followed)

ensured Mughal domination over much of what it today India, Pakistan and

Afghanistan. The Mughal legacy seems to have been principally

cultural. Among the impacts on Indian society the Mughals are credited

with are centralising government, amalgamating Persian art and culture

with native Indian styles, Mughlai cuisine, the Urdu language, as well as new styles of

architecture and landscape gardening.

In the long run it's

difficult to tell whether an alternate destiny would have made much of a

difference to the Indian people's ability to fight off the British

(we talked about that when we discussed the Battle of Plassey in July, 2009).

Perhaps nothing any alternative

history could have produced is as freakish as this image of an Indian

and a Pakistani in Mughal armor facing off over cricket, the game

brought by their English conquerors...

But one odd and critical lesson that Panipat did NOT

teach the Mughals was the need to continue to develop gunpowder technology. The

technology and, more importantly, the attitude towards the technology

just didn't take hold anywhere in India.

But one odd and critical lesson that Panipat did NOT

teach the Mughals was the need to continue to develop gunpowder technology. The

technology and, more importantly, the attitude towards the technology

just didn't take hold anywhere in India.

When the French showed up to

provide 18th Century artillery to their Indian proxies they didn't find a

cadre of professional gunners you'd expect from two hundred years of

familiarity with the weapons. The result? Well, we talked that all over when we discussed Plassey, and the result was a century of British occupation and some very interesting - and in many cases horrifying - social and political consequences.

Touchline Tattles: Among the prizes that Babur is supposed to have won at Panipat, perhaps the most gaudy was the Koh-i-noor diamond,

the famed "Mountain of Light", that is supposed to bring doom to male

wearers and was, among other things, the object of George MacDonald

Fraser's Harry Flashman's cupidity during the First Sikh War.

So the moral of this bloody story may well be that there's almost no tale that can't be spun from even the grimmest of histories.