Last time we looked - very briefly! - at the geopolitical buildup to August 1914.

The tl:dr version is that:

1) Europe in the waning years of the 19th and the opening of the 20th Centuries was a cross-cutting tangle of alliances meant to reassure the major powers that they wouldn't be isolated in a Great Power war.

2) These included:

a) Germany and Austria-Hungary, a peculiar and one-sided arrangement that seems to have persisted because i) Austria needed German economic and military strength, while ii) Germany needed SOMEbody to be their pals, and the Austrians were that desperate.

b) Italy and the Ottomans were kind of strap-hanging on to the Austro-German alliance, but i) Italy was pretty much the definition of "not really a Power" AND pretty much hated the Austrians, while ii) the Ottomans weren't useful for much of anything in Europe AND were pretty much "The Sick Man" they're conventionally portrayed.

c) On the "other side" were France and Russia, forced into an arranged marriage when Germany dumped Russia and France was looking for help to offset its economic and demographic weakness vis-a-vis Germany.

d) Great Britain wasn't really sold on all this Continental dick-waving, but i) had patched things up with France because of concerns about Kaiser Wilhelm's idiotic Navy fetish, and ii) had an arrangement with Belgium, who, sensibly given the aggro dudebros all around, had declared their absolute neutrality on the whole Franco-German pissing contest.

3) When the political crisis in the Balkans that exploded at the end of June (and, remember, Franz Ferdinand was just the final spark; the problems between Austria-Hungary, Serbia, Russia, the Ottomans, as well as the Balkan minorities within and without the Austrian borders, had been festering for decades) the immediate military concerns of the various powers were (in alphabetical order):

Austria-Hungary: defeating Serbia before the Russians could mobilize and threaten the northern regions of Bohemia and Moravia (in what are now the Czech Republic and Slovakia) and Galicia (in modern Poland):

|

| By ArdadN - Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5867649 |

France: A German invasion (I know - it was that simple, but not easy...)

Great Britain: Kind of nothing, at first. France versus Germany? Not their problem, tho I'm sure Herb Asquith and Downing Street were giving the HochSeeFlotte the side-eye just in case...

Italy: Not happy to be dragged into a European war by the fucking Austrians (bastardos!) over some damn thing in the Balkans.

(This eventually led to Italian reneging on their Central Power-alliance commitment, BTW.)

Ottoman Empire: Kind of wanted to slap Russia, but the overall involvement was a fuckup. Turkish historian Kemal Kaspat summed it up as follows:

“Ottoman entry into the war was not the consequence of careful preparation and long debate in the parliament (which was recessed) and press. It was the result of a hasty decision by a handful of elitist leaders who disregarded democratic procedures, lacked long-range political vision, and fell easy victim to German machinations and their own utopian expectations of recovering the lost territories in the Balkans."

So, yeah, kind of a fuckup.

Russia: Fulfillment of promises to the Slavic nationalists in the Balkans, as well as a fear of Austro-German attacks from Galicia and East Prussia.

Great Power Chess: Germany Moves First

Of the Powers Germany was in what appeared to be the scariest military position.

Everyone else had a border to worry about, but Germany had two; in the East against Russia, in the West, France.

(Technically so did Austria-Hungary. But the Serbians were feisty, not insane, so they weren't coming at Vienna. Russia? Ohfuckyes.)

The Eastern German border around what is today Poland was 1) open geographically - rivers (and other water bodies like marshes and lakes) were the only real defensible obstacles - and 2) perfect for the "mass effect" of Russian attacks.

The whole "Russian Steamroller" was a thing for a reason.

German war planning, then, had to either figure out a way to fight a modern, dangerous French Army in the West while simultaneously facing a monster Russian invasion from the East, or...

Strike quickly and decisively on one front, defeat that enemy, then turn to the other side of Germany to beat the other.

Meaning that in the 1914 war chess game Germany was playing white and had to move first.

When you look up at the whole "Eastern border" description you can see why that move also had to be to the West. Russia had bodies and ground to lose and keep fighting; trying to force a Russian "Sedan 1870" was a mug's game. If beat along the border the Russians would just take their lickings and fall back into the vast expanse of western Russia.

France couldn't. Simple distances show why:

So prewar German planning (after the lapse of the Reinsurance Treaty pretty much ensured a two-front war) was based on:

1) German mobilization - both troop formation and rail transport to the forward railheads - running more quickly that either France or Russia's,

2) Fighting delaying actions in East Prussia, while

3) Attacking France and knocking it out of the war ASAP.

But.

How to do this?

Because the French knew what had to happen as well as Germany did, and had the advantage of knowing where it was coming from: the former pieces of France grabbed in 1871, Alsace and Lorraine.

Le système Séré de Rivières

After the debacle of 1870 the French Government formed a committee to develop a defensive barrier to the next foreign (presumably German) invasion. The Wiki entry has a nice summary of this:

"France created the Defence Committee (Comité de défense), which was active between 1872 and 1888, whose mission was to reorganize the defence of the French frontiers and coasts. It was necessary to compensate for the lost territories of the north-east; to modernise old fortifications, which had been shown to be wanting in the last war and to create new fortifications proof against modern weaponry using new and more powerful explosives."

This organization oversaw the creation of the fortifications known as the "Séré de Rivières" system after the engineer officer who ran the committee from 1874 to 1880.

These forts ran the length of France's northern and eastern borders, but were densest (and strongest) in the northeastern corner along the Franco-German frontier:

Note that this wasn't intended as a wall, but more like a sabo dam; separated blocking points with corridors between them that would funnel attackers (the green arrows in the cartoon above) where they could be engaged by the French maneuver forces and defeated.

Now...mind you, by 1914 this system had a big problem, and I do mean BIG...

The development of superheavy artillery like this Krupp 420mm howitzer meant that the forts couldn't defend themselves; typical fortress guns ran in the 75mm to 155mm caliber.The 155mm 155 "L de Bange" design from 1877 was the heaviest artillery the de Rivieres forts mounted, with a maximum range of about 13,000 meters.

The superheavies' maximums ran from 8-9,000 meters up to 14-20,000, and they were semi-mobile (though slow to emplace and displace) which meant that even when they didn't outrange the fortress batteries they were difficult to hit without forward observation.

The forts had no such benefits.

Still, even outdated, the de Rivieres forts presented some difficulties to a German assault that depended on speed. The monster cannon meant that even the strongest fortification could be destroyed or taken. But that would take time, and time wasn't on Germany's side.

So we're back to where we were when we talked about sieges. The only ways to crack the walls was over - escalade - through - breaching or treachery - or under - mining. All took too much time or too many lives.

The alternative is obvious when you look at it.

Around.

If you attack where the forts aren't, they can't slow or stop you.

Which is where we meet this guy:

A Man, A Plan, A Strong Right Wing...Schlieffen!

Alfred von Schlieffen (1833-1911) was a Prussian of Prussia, son of a major in the 19th Century Prussian Army. The only unusual part of the junior von Schlieffen story is his choice to skip the more usual cadet school route to a commission for the University of Berlin.

Instead Alfred chose the Einjährig-Freiwilliger ("One-Year Volunteer") option, which the von Schlieffen Wiki entry kind of messes up.

The volunteer system - let's use the common shorthand "EF" for it - was a way for wealthy and/or aristocratic types to shortcut the officer training program. You came in like a regular draftee, but 1) only for one year as opposed to two or three, and 2) paid for everything yourself. The EF Wiki entry is much better at describing this:

Instead of the reserves, von Schlieffen was tapped for a regular officer career and started the Kriegsakademie - the Prussian Sandhurst or St. Cyr - in 1858 and was commissioned three years later in the topographic bureau of the Generalstabs, the Prussian General Staff."...would opt to serve a one-year term rather than the regular two or three-year conscription term, and who would be allowed a free choice of service branch and unit, but who were obliged to equip and support themselves at their own expense throughout. In today's monetary value this cost might equate to at least 10,000 Euros, which restricted the option to members of the affluent social classes, considered to be "officer material", who hoped to pursue a Reserve-Officer career path."

A very Prussian officer career followed. War service in 1866 against Austria (including the Battle of Koniggratz, which I should really write up someday) and in France in 1870.

Advancement through the ranks, although I get the sense that his superiors kind of saw him as a Big Military Brain - Schlieffen got a lot of staff postings under the Prussian (and Imperial German) flagpole - so more staff than troop unit time.

By 1886 he was a two-star Generalmajor, a three-star Generalleutnant by 1888 and in 1891 nicked the top Army job, Chief of the General Staff.

This meant von Schlieffen had tremendous influence on German military policy...but not alone. Ian Senior's 2012 work Invasion 1914 has a good breakdown of the forces in play in the Imperial war planning arena.

These included Schlieffen as Chief of Staff, but also the Prussian Ministry for War (Preußisches Kriegsministerium), the three-star corps commanders (all 23 of them), and of course the Emperor and the Imperial "War Cabinet".

You need to keep this in mind, because it plays a huge part in the "Schlieffen Plan" story.

Because there were plans, and then there were budgets, and though Schlieffen could make the former the Minister for War had control of the latter.

So a lot of Schlieffen's "planning" had to do with shaking Reichsmarks out of the Minister and the rest of the Imperial machinery, including the Emperor, the Cabinet, and the Reichstag - all of whom had their own objectives.

Ch-ch-ch-changes

When he set his ass behind the Chief's desk in 1891 Schlieffen inherited a general war plan that (to sum it up briefly) anticipated two fronts, Russia and France, and doped out a quick strike to the East that would catch the Russians still mobilizing and grab some land and cash to use negotiating a favorable peace.

In the West, though, the de Rivieres forts ruled out an aggressive move. The plans prescribed a defensive fight to pull the French Army out of their fortified lines where they could be counterattacked and defeated.

Schlieffen haaaated this, both because he was an aggro kind of guy and because he wanted to win outright rather than depend on the tricksy machinations of politicians and diplomats. Senior (2012) details his work through the process of changing up the general war plan between 1891 and 1906.

He changed to defense in the East, for all the reasons we've detailed (plus improvements in the Russian defense lines around East Prussia).

Then planned that the attack would come in the West, where the Rhine armies would be heavily weighted-up to include the new superheavy artillery to crack the fort problem. Schlieffen counted on a quick victory there (somehow) and then the efficiency of the German rail system to transfer forces East to hold off the Russian hordes.

But.

The fort problem in the West remained difficult. Senior (2012) explains: "...in 1894 he briefly toyed with the idea of outflanking the fortress belt to the north of Verdun while at the same time pinning down the French center by means of an attack on Nancy, but reluctantly came to the conclusion that he did not have enough men for both tasks...in 1897...he returned to the theme..."

The major problems with these schemes were manpower and movement. One solution was that Schlieffen wanted more maneuver forces, up to seven full Armeekorps. The Minister for War repeated replied not just no but fuck no.

The other issue was the rough and close terrain along the area along the Alsace-Lorraine frontier "north of Verdun"; few or no rail lines; small, narrow roads and not many of those. The area was okay for defense, not so much for a major attack.

That's probably what got Schlieffen thinking that the way to go was around, not through.

Specifically, around France through Luxembourg, Belgium, and (he'll get there) Holland.

This first emerged in the 1899 plan set.

The plan - and these things were called "Aufmarsch" (deployment) plans, more a general set of instructions for the who went where than what a modern GI would consider an "operations order" - called for a big right-wing swing up through Belgium, and Luxembourg. It was still relatively modest but you can see Schlieffen already thinking "big enveloping hook".

So that's where things still stood in 1904.

Then several pieces of news arrived. The French extended the fortress lines to the northwest, past the Franco-German border towards Belgium and Luxembourg.

Russia, meanwhile, was getting handed its ass by Japan.

That spring Schlieffen mounted up his boys for his semiannual "staff ride" along the Western frontiers. Apparently this was his thing; he'd trot around the prospective engagement areas, throwing out ideas and asking his staff pogues to snipe at them.

It sounds like it was all very taxing and saddle-sore-ass-wearying, but it was Schlieffen's way of testing his ideas.

The 1904 ride produced Aufmarsch I (West) in 1905; what we think of when we think "Schlieffen Plan"; big sweep - seven full Armies - through Belgium and the dangly bit of southeastern Holland. These heroes would strike west deep into central Belgium then hook back south and east into France to trap the presumed French offensive that would have rammed into the Metz/Rhine region of the Franco-German border.

This was the plan Schlieffen tossed out to his staff in his final staff ride, and invited three staffers to take swings at it. Senior (2012) discusses this ride in detail (p. 32-34), but the tl:dr is that in Schlieffen's mind, anyway, his "big sweep" plan beat the three opponents' rebuttals. It was a war-winner.

The "final version" emerged as what's called the "GroBe Denkschrift" ("Great Memorandum") distributed after Schlieffen's retirement, in January, 1906.

The basic idea was that a huge portion of the German Army would be committed to the West, leaving the East to a small defensive force to delay the (presumably lagging) Russian advance.

Then a huge portion of the Western force - 71 of a possible 81 divisions, including a ginormous assembly of Reserve ("Ersatz") Armeekorps to be raised on mobilization - would drive through the Dutch "Maastricht Appendix", Belgium, and Luxembourg, turning the French left and then looping in behind the Franco-German border - ideally west of Paris - to crush the French Army between the swinging German left wing hammer and the German right wing that would buttressed by the German border fortress belt anvil.

The "conventional narrative" then goes on to detail a series of gradual modifications to Schlieffen's original all-or-nothing left-wing sweep effected under the aegis of Schlieffen's successor, Helmuth Johannes Ludwig Graf von Moltke (usually referred to as "Moltke the Younger"), particularly:

1) Refusal to cross the Dutch border. (Moltke explained that a hostile Holland would close the Rhine ports, "closing Germany's windpipe", as well as possibly opening a debarkation point for British troops),

2) Strengthening the left wing by pulling one right-wing army out to double the size of the left, and then

3) Further weakening the right wing by pulling out more troops to reinforce East Prussia in 1914.

Supposedly these modifications collectively doomed the actual invasion by denuding the German right of enough force to accomplish its mission. Hence the repetition of the apocryphal Schlieffen deathbed admonition "Keep the right wing strong!" and the conventional "wisdom" that the unmodified Schlieffen Plan would have succeeded.

There's a good discussion of this "narrative" tradition in the "Civilization Fanatics Center" blog by someone named "Dachs" out of Russia.

(I know nothing about this guy, or his intent in posting the piece. It's still a useful analysis, so, spasiba.)

Apparently the "narrative" appeared in the early post-WW1 period, among historians and military theorists like Basil Liddell-Hart, and was amplified in the aftermath of WW2, principally in a 1958 book by Gerhard Ritter, Schlieffen Plan, Critique of a Myth.

The Ritter book centers on a series of previously unpublished drafts of the 1905 memo, and it reflected his take on Imperial German militarism, which "Dachs" summarizes as:

"Schlieffen's militarism precluded any discussion of whether invading Belgium and the Netherlands was morally or legally correct, and instead sent a million men headlong into infamy on the grounds of national interest and winning the war. His uniquely German sense of precision had timed the campaign so exactingly - down to the hour, as Ritter had it - and demanded that France be defeated in forty-two days, so as to turn on Russia before it could mobilize its own armies."

But.

"Dachs" then runs down the subsequent scholarship of the 1914 invasion, including the work of Terence Zuber's 1999 The Schlieffen Plan Reconsidered, which posited that the 1905 drafts Ritter relied on and the supposed "ideal" 1906 Denkschrift "plan" were, in fact;

"...relics of that omnipresent feature of army politics, a budget debate. Schlieffen wanted more troops and more money to hire them with, so he drew up the "war plan" employing a number of soldiers outlandishly higher than anything the Germans could employ in 1905 in order to demonstrate how kickass the German military could be if the Reichstag would but give it the cash necessary to implement Schlieffen's vision. Explaining it as an actual war plan, Zuber said, made no sense."

Among the other "Schlieffen skeptics" Martin van Creveld's work on the logistical issues which we discussed in the Battle of the Marne piece suggested that:

"...an attack through Belgium simply could not have incorporated the numbers of troops Schlieffen envisioned in Ritter's memo, even in peacetime...van Creveld argued that if Moltke had dispatched more men to the right flank, they would have just been an extra drain on already-overstretched supply lines, and the Germans might have run out of steam even before they reached the Marne."

In conclusion, "Dachs" says: "What does it mean for European diplomacy if Germany's war plan was not always predicated on a war with both Russia and France, or an offensive against France? The Sonderweg and the Griff nach der Weltmacht (NB: two schools of thought regarding the connection between German geopolitical thinking and the resulting aggressive military adventures) have been generally disproven, for various reasons (which I might go into in another history article). But that does not mean there is a dominant interpretation to replace them. So the state of historiography on the period today: many voices, but no chorus."

Okay, then...so what? What does all this mean?

So.

The bottom line seems to be that, regardless of the details of operations or the geopolitical intent, the German 1914 war plan called for 1) a defensive posture along the Franco-German border coupled with 2) a big hook through Belgium - with the implied acceptance of that triggering a British declaration of war and a British Expeditionary Force landing on the Channel Coast - to avoid the fortress belt and round the west end of the French (and British) defenses.

The right-wing armies would then "roll up" the Allied defenses from the northwest most quick smart, forcing evacuation of the Verdun/Toul/Epinal/Nancy fortresses and - presumably - capitulation.

To do that, the German reconnaissance elements had to be sure to find that open flank, while the security elements along the French border had to keep the Deuxeme Bureau from spying out weak points in the German defensive lines.

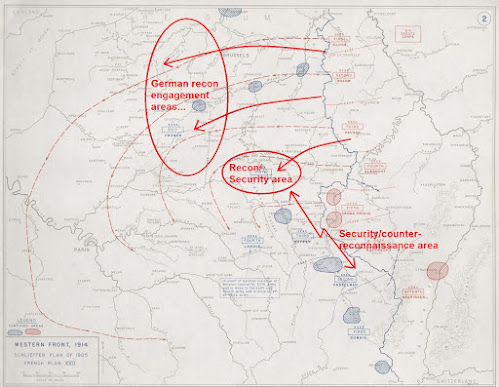

So cooked down to general mission tasks, based on the actual 1914 Aufmarsch, the job(s) of the German reconnaissance and security/counter-reconnaissance elements looked something like this:

1. Due west of the northern start lines - the central Belgian plateau from roughly the fringes of Antwerp to the areas around the French fortress town of Maubeuge - the primary mission was reconnaissance. The commanders of the German First and Second Army needed to know where their enemies were - and, even more importantly, weren't - to ensure the right wing sweep was wide enough to net their catch.

These areas were complicated by the "big-picture/small-picture" range of information needed. The overall German commanders - Moltke and the Emperor and his War Cabinet - needed long-range planning intelligence. Meaning well ahead of the forward infantry strength so those march columns could be routed or re-routed to envelop the Allied troop units.

The individual Army commanders (Kluck with First, Bulow with Second) also needed tactical intelligence, though, in order to figure out their most effective course of action for engaging those Allied units.

Overall, this was the trickiest and most recon-asset-consuming part of the theater.

2. To the southeast - west of Luxembourg, mostly in and around the Argonne Forest - the mission was more complicated. It still had a reconnaissance component, but that was more for the tactical and local needs of Third and Fourth Armies rather than the strategic recon needs of the first two armies.

And in that area the German cavalry and light infantry would need to screen out French (and/or British) recon teams to prevent the premature discovery of the "hinge" in the German line.

3. Furthest to the southeast - ahead of the Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Armies along the Franco-German border - the primary task was screening, fighting off French cavalry and their light infantry recon units to mask any potential weak points in the German defenses and keep the anvil together until the hammer could strike.

We're going to get deep in the weeds of "who's doing all this stuff", be before that we're going to look at the Other Side of The Hill; France, and its war plans that all this strong-right-wing-ing was intended to unhinge and knock sideways.

Next: I Got XVII Plans But the Krauts Got One