From the first day he came through the door into the battalion aid station his cramped, pointed-toe walk made Doc Luna seem like a stranger even among a whole group of strangers.

From the first day he came through the door into the battalion aid station his cramped, pointed-toe walk made Doc Luna seem like a stranger even among a whole group of strangers. We’d been pulled in from all over Division – from all over Fort Bragg – to fill the battalion for the Sinai deployment. I’d volunteered from my first outfit over in Third Brigade; we had medics from the Army hospital over across post and medics from other units we’d never heard of over on Smoke Bomb Hill and even from distant COSCOM, a place a fabled as CloudCuckooLand, where we’d heard of the “Cosmonites”, weird, Army-like hominids that were said to inhabit dwellings they never left, like the so-called “civilians” we were said to be defending, who thought of trees as landscape instead of a combination of dwelling and fortification and dirt as walkway instead of home and building materials.

We’d been pulled in from all over Division – from all over Fort Bragg – to fill the battalion for the Sinai deployment. I’d volunteered from my first outfit over in Third Brigade; we had medics from the Army hospital over across post and medics from other units we’d never heard of over on Smoke Bomb Hill and even from distant COSCOM, a place a fabled as CloudCuckooLand, where we’d heard of the “Cosmonites”, weird, Army-like hominids that were said to inhabit dwellings they never left, like the so-called “civilians” we were said to be defending, who thought of trees as landscape instead of a combination of dwelling and fortification and dirt as walkway instead of home and building materials. Most of us had met less than a month before, and had barely learned each other’s names.

But Doc Luna was different.

He was almost silent, for one thing, in a group of medics.

Monosyllabic, at best. Practically mute

Most grunts will tell you that medics chatter like starlings but in truth, starlings are the mimes of the medical trade. Army medics, generally speaking, have never left a person or a place unimproved by talking. Stories, jokes, lies, gossip, and imprecation: there is almost nothing that a medic won’t talk about. Boasting is considered gauche, which means that war stories and sex stories usually have to be edited for time and content, but pretty much any- and everything else is jaw fodder.

But not for Luna.

And it was more than just reticence. Within days a couple of us had encountered the touchy, prideful, almost angry side he hid behind the impassive face. Misheard words became insults; casual avoidance was taken as slight. Before he had the chance to find his place among us he became a figure of mild amusement, then distaste, then distain.

He arrived at the airstrip at Ras Nasrani a man alone in a uniformed crowd.

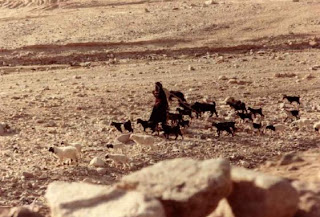

He idled through the transition period bored and irritable as the rest of us. His personal peculiarities were lost amid the new strangeness of place and people. We forgot to ignore him as we goggled at the distanceless desert that stretched an infinity between the mountainous highlands to the impossibly blue Gulf of Aqaba, at the black tents of the bedu with their begging and herds of scrubby goats,

at the dribble of passersby and tourists that transited the Sinai in the winter; the British officer and his wife, tanned and somehow managing to be horsey even mounted in a dirty Land Rover, the German girls reeking of friendly sex and cigarettes, the odd Eurowhatsit with his Chitrali cap and battered bicycle and ajima-load of bedrolls and bundles.

at the dribble of passersby and tourists that transited the Sinai in the winter; the British officer and his wife, tanned and somehow managing to be horsey even mounted in a dirty Land Rover, the German girls reeking of friendly sex and cigarettes, the odd Eurowhatsit with his Chitrali cap and battered bicycle and ajima-load of bedrolls and bundles.So it wasn’t until we were parceled out to out first OPs that we got reminder of the oddity that we’d wondered at a bit at first.

Every OP – “observation post” – was a tiny island of humanity in the midst of one of the world’s great rocky deserts. A ring of sharp concertina wire enclosing sandbagged bunkers used typically only by camel spiders and scorpions, a pair of aluminum trailers (one for a dwelling, the other combination kitchen and commo shack), a water tower over a shower stall, a one-hole burn-out latrine.

Each one had a distinct character. The Checkpoints; One-Alpha, Two-Alpha and Three-Alpha, were bustling, busy places full of traffic and activity along the Main Supply Route or “MSR” that ran along the eastern littoral of the peninsula. Others, like OP3-2, were along large wadis that formed the passageways through into the interior and were often visited, or even tenanted by, the Bedouin of the Sinai. Others, like OP3-11 on Tiran Island and Remote Site 3-5 were as isolated as men could be in an age of radio and aircraft; fragile specks of human business in a land of rock and heat and stillness, cold and light and dark and wind.

Each one had a distinct character. The Checkpoints; One-Alpha, Two-Alpha and Three-Alpha, were bustling, busy places full of traffic and activity along the Main Supply Route or “MSR” that ran along the eastern littoral of the peninsula. Others, like OP3-2, were along large wadis that formed the passageways through into the interior and were often visited, or even tenanted by, the Bedouin of the Sinai. Others, like OP3-11 on Tiran Island and Remote Site 3-5 were as isolated as men could be in an age of radio and aircraft; fragile specks of human business in a land of rock and heat and stillness, cold and light and dark and wind.I hope it was just bad luck that the first OP Doc Luna was sent to was RS 3-5. I’d hate to think that there was a Plan behind that, because to believe that would be to suspect that the Calvinists were right and that we are, indeed, all sinners in the hands of an angry God. Because the remote Remote Site was not kind to Doc Luna.

I liked the Remote Site, liked it's barrenness and the echoing clatter of stones in its canyons, the fossils of oysters and squid telling of the ocean that had once bathed this desolate place. We returned with tales of all-night card games and patrols sneaking down tortured wadis to find Bedu fires years dead.

I liked the Remote Site, liked it's barrenness and the echoing clatter of stones in its canyons, the fossils of oysters and squid telling of the ocean that had once bathed this desolate place. We returned with tales of all-night card games and patrols sneaking down tortured wadis to find Bedu fires years dead. The squad that came in from RS 3-5 brought with them some disturbing stories. Stories about their medic muttering to himself, glaring at some of the other soldiers, and shouting and fighting in his sleep. Disappearing at random times and then turning up in odd places like inside the food storage bins or inside a vacant bunker. Arguing with the squad leader and refusing some of his orders.

The squad that came in from RS 3-5 brought with them some disturbing stories. Stories about their medic muttering to himself, glaring at some of the other soldiers, and shouting and fighting in his sleep. Disappearing at random times and then turning up in odd places like inside the food storage bins or inside a vacant bunker. Arguing with the squad leader and refusing some of his orders.Sergeant Ramon, the medical platoon sergeant, called Luna in and tried to talk to him. The result of the meeting was not promising; Luna accused several of the squad’s soldiers of improbable maliciousness, and spoke bitterly of a secret plot against him. SFC Ramon asked Luna if he wanted to see the commander but received only a shake of the head. Both men parted unsatisfied.

The next deployment in sector passed quietly; Luna was sent to busy Checkpoint 3-Alpha, where he got on well enough. His squad leader returned with only the observation that Luna seemed a trifle over-concerned with the chlorination of the water supply, not a real problem since the checkpoint had an external water source.

On the more distant OPs the potability of the water WAS a real hazard. In many places the water resupply truck visited no more than once or twice a month, and in the black plastic tanks the chance for bacteria to flourish between fillings was ever-present.

On the more distant OPs the potability of the water WAS a real hazard. In many places the water resupply truck visited no more than once or twice a month, and in the black plastic tanks the chance for bacteria to flourish between fillings was ever-present.

The medics’ two most constant tasks on those outlying OPs was to burn out the used Army chow in the half-barrel under the latrine, and to check the chlorine content of the water daily and to add the chemical whenever the level grew riskily low. It was a repetitive chore of delicate brutality, fiddling with tablets and water and the plastic gadget with its color wheel and testing cells, dumping the eye-searing pool chlorine into that hot, echoing black vault. Too much and the GIs wouldn’t drink, no matter how brutal the heat. Too little and the possibility of gut sickness and panicked flight to the reeking latrine was a fear buried in the quiet place of all of our heads.

For all the blister lancing and sunburn anointing, our management of the water was the most constant influence we exerted on the other soldiers with us on the OPs. We were the sommeliers of water; sipping, measuring, testing, judging. Which level of chlorine will go with tonight’s Chili Mac? Should we add a pinch more for a robust “L’eau d’Esther Guillaumes” to accompany the morning’s dried egg omelettes? What flavor of water “carries” well on a long patrol, as opposed to one which “sits” for a more sedentary gate guard lifestyle..?

I spent the next two weeks out on OP 3-11 on “the island” of Jazirat Tiran watching seabirds soar over the Red Sea into the Gulf of Aqaba and patrolling the uninhabited rock with my squaddies wearing nothing but hat, boots, rifle and LBE equipment harness. I heard nothing from the rest of the battalion until I returned to the mainland.

I spent the next two weeks out on OP 3-11 on “the island” of Jazirat Tiran watching seabirds soar over the Red Sea into the Gulf of Aqaba and patrolling the uninhabited rock with my squaddies wearing nothing but hat, boots, rifle and LBE equipment harness. I heard nothing from the rest of the battalion until I returned to the mainland.While I was clutching and encouraging the shimmying old Huey to make it out to Tiran Island, Doc Luna rode out with his squad up the wadi to OP 3-3. The troopers said that he seemed no different than ever, perhaps a little more withdrawn, perhaps a little less relaxed, but no one really cared for him, so no one really bothered to notice. He was just there, ol’ Doc Luna, the oddball medic. He scuffed around the OP the first few days with the rest of the guys, squinted into the sun, looked on as the others complained their now-familiar complaints about the heat, the dust and the wind. Ate alone, and in silence.

The third or fourth day several of the squaddies complained about the water. It was nasty, full of chlorine, like pool water, they said. One of the team leaders drew a cup from the tank and reported to his squad leader that the men were right; the water was so chlorinated as to be practically undrinkable.

The third or fourth day several of the squaddies complained about the water. It was nasty, full of chlorine, like pool water, they said. One of the team leaders drew a cup from the tank and reported to his squad leader that the men were right; the water was so chlorinated as to be practically undrinkable.The squad leader, a soft-spoken young sergeant, found Luna in the bunk-trailer and instructed him to open the tank lid and burn off the chlorine; Luna’s response was a grunt and a glare. The next day the water tasted worse, if anything. The staff sergeant brought one of his team leaders to witness the order he gave to Doc Luna: bring down the chlorine level immediately. No excuses.

What happened next was described to me as a delighted garble of reportage, inference and innuendo. Some of the soldiers claimed that Luna growled like an animal, snapping and shaking his head, muttering curses and threats to the noncommissioned officers and all the soldiers. Others said that he remained impassive but seemed to swell in the threateningly reptilian way. A third group described his face as staring, eyes fixed and jaw clenched as he moved through the OP like a badly-played marionette, ignoring the soldiers idling the hot afternoon away.

What everyone agreed on was that he had gone to the water tank and drawn a 5-gallon jerrycan full of the awful pool water. After filling this, they said that he had taken the chlorine test kit out to the edge of the open helicopter landing area and had carefully laid every cheap plastic piece out on the stones before thoroughly splintering them with one of the orange border boulders. Private Ahlers solemnly reported that the largest single fragment was no bigger than his pinky toe. I could only agree, having no wish to see Ahler’s pinky toe.

Everyone then said that Luna had then clutched his jerrycan to him and stalked back to the billet trailer, where he crawled into his bunk with the can and the K-bar knife he had carried on his LBE. Any and every attempt to address him was met with weird yowls and cries and curses and jabbings of the knife. At last the squad retreated to the TOC trailer to call the sector control and report that their medic had gone ape, gonzo, bugnuts, batshit crazy and cry for help.

Everyone then said that Luna had then clutched his jerrycan to him and stalked back to the billet trailer, where he crawled into his bunk with the can and the K-bar knife he had carried on his LBE. Any and every attempt to address him was met with weird yowls and cries and curses and jabbings of the knife. At last the squad retreated to the TOC trailer to call the sector control and report that their medic had gone ape, gonzo, bugnuts, batshit crazy and cry for help. Everyone there on OP 3-3 that day had a different picture of the scene when the Dutch military police arrived with the battalion surgeon, the provost marshal and some sort of psychiatric fellow from Al Gorah. I heard of wild struggles, crazed rants and long, babbling soliloquies from the tormented Luna, whispered conversations, hasty conferences until finally the MPs crashed into his bunk and extracted the thrashing, screaming madman in a flurry of arms and legs and fists. Everyone agreed that Luna was finally securely strapped into the white jeep, silent, defeated, head down but his jerrycan still beside him for the journey down to sector control, and from there to the troop medical clinic at South Camp. Rumor went wild from there; he had bitten one of the doctors in the face, he had been “put in one of them Hannibal Lector mask things” as Specialist Goines described it, he had been flown out of the Sinai that very night. Rumor also had other, even more impressive tales that most of us, while agreeing were probably bullshit, were all secretly hoping were true. The madness of one of our fellows had an eerie delight to us, novelty in the midst of boredom, a fearsome but distant danger like a firefight seen from a hilltop far away.

Everyone there on OP 3-3 that day had a different picture of the scene when the Dutch military police arrived with the battalion surgeon, the provost marshal and some sort of psychiatric fellow from Al Gorah. I heard of wild struggles, crazed rants and long, babbling soliloquies from the tormented Luna, whispered conversations, hasty conferences until finally the MPs crashed into his bunk and extracted the thrashing, screaming madman in a flurry of arms and legs and fists. Everyone agreed that Luna was finally securely strapped into the white jeep, silent, defeated, head down but his jerrycan still beside him for the journey down to sector control, and from there to the troop medical clinic at South Camp. Rumor went wild from there; he had bitten one of the doctors in the face, he had been “put in one of them Hannibal Lector mask things” as Specialist Goines described it, he had been flown out of the Sinai that very night. Rumor also had other, even more impressive tales that most of us, while agreeing were probably bullshit, were all secretly hoping were true. The madness of one of our fellows had an eerie delight to us, novelty in the midst of boredom, a fearsome but distant danger like a firefight seen from a hilltop far away.What was true fact is that we never saw Luna again.

I remember sitting at the park bench outside the cheap modular building that Luna and I had shared a fortnight previously and wondering what had happened, why he had come to this time and this place to disintegrate so utterly, who the man had been inside that silent face. Had he always been somehow flawed, fractured inside, just waiting for the wrong combination of people and things and surroundings to fall to pieces? Or was he just like all of us, was his fall the fall that could overcome any of us any time for no reason at all…just the relentless, hopeless erosion of self and sanity, the loss of reason; quick and hopeless, or frantically scrabbling to keep the shattering pieces of his person together?

I had no answer from the evening noise of South Camp, the generators’ humming clatter and the sound of Egyptian pop music from the mess hall kitchen down the other end of the camp. The answer was locked inside the head of the beaten man who flew away, high and northwards in the night sky over the Mediterranean, as the sun went down over the mountains to the west.

I had no answer from the evening noise of South Camp, the generators’ humming clatter and the sound of Egyptian pop music from the mess hall kitchen down the other end of the camp. The answer was locked inside the head of the beaten man who flew away, high and northwards in the night sky over the Mediterranean, as the sun went down over the mountains to the west.

8 comments:

Another great installment. I have always maintained that names are destiny, and Doc Luna met his inevitable end.

Everyone has a breaking point, and irritating people often find others who will hasten their unraveling. It is naught but the stuff of Greek drama.

The 1st Sustainment Command Shoulder Sleeve Insignia was excellent, looking a bit like an Obama poster, but as well, would have looked sporting on Doc Nelscott's uniform that fateful morning, no?

p.s.--if that photo is actually Luna, he looks, how shall we say, a bit too intense, like he is about to go off at half-cock. The sort who would feel offense even when none was forthcoming. Paranoid.

Lisa: I threw in the picture because it did fit the story nicely but...no.

That's me.

Almost thirty years ago, toasted to the socket from being up all night on CQ drinking Jolt and eating bad pizza. And I was ready to go off like a bad firework at that moment, yes.

"And I was ready to go off like a bad firework at that moment, yes."

I wanted to say he was wasn't bad looking, either, but you see I have a thing for crazy-looking men -- a habit I am trying to kick! So I decided I would speak to all of the off-putting things. (Alas, intensity still has an allure. . .)

Lisa: I'm afraid I would have disappointed you - I had a lot of growing to do at the time, and it took everything life could throw at me to make that happen.

I certainly would have done my bad, mad, and dangerous-to-know best to be worth your affections. Even back then I was a hopeful romantic.

The next Sinai story involves that romance and the consequence of 6,000 miles of distance...

"I certainly would have done my bad, mad, and dangerous-to-know best to be worth your affections. Even back then I was a hopeful romantic"

Funny how men (people) do try these avenues of approach in order to get love, sometimes. Then again, for some they are merely egotistical productions with no hoped-for positive gain beyond the pleasure of the immediate emotional discharge.

I will anticipate your Sinai installment.

"egotistical productions with no hoped-for positive gain beyond the pleasure of the immediate emotional discharge."

Pretty well describes 58% of all male emotional attachments between the ages of 14 and 54.

The remaining 42% are those of us who continue in that style until incontinence and senility render any romantic attachment impossible...

We're a sad gender, sometimes...

With your candor, you enlighten me.

I think think games and isolation are silly and sad. As you note, it takes some effort to grow up to be big and strong emotionally. As many of us are betrayed by our society or families, it devolves to our relationships of choice to midwife us to maturity.

Alas, the road is mined with damaged people mostly struggling to get their needs met. Like Ms. Lennox sang, some gets it via using, and some by being used. We must break out of our repetition compulsion if we are to become.

Rarer is honest kindness and care sans agenda.

Post a Comment