Forces Engaged:

Egyptian Mamluk: roughly 20,000 under the Mamluk Sultan of Egypt, Saif addin Qutuz. One of Qutuz' subordinates was the mamluk al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baybars al-Bunduqdari or "Baibars", whom we will hear more of later.

Mongol: Either one or two tumens; between 10,000 and 20,000 horsemen under Kitbuqa Noyan, Turkish Christian and lieutenant of Hulagu Khan.

The Situation: It is difficult to overstate the impact that the Mongol invasions of the West had on the minds and bodies (and cities, towns, farms and villages!) of the peoples they encountered.

The Situation: It is difficult to overstate the impact that the Mongol invasions of the West had on the minds and bodies (and cities, towns, farms and villages!) of the peoples they encountered.

The Mongol Empire is one of the amazing stories of Eurasian history.

From a band of horse nomads in the 12th Century the Mongols literally burst out of Asia in two generations.

Ghenghis Khan led the horsemen west after 1218 until his death in 1229; by 1240 his son Ogedai's forces were hammering on Poland and eastern Germany and were poised to push into southwest Asia and destroy the Abbasid Caliphate.

No contemporary army had found either the tactical solution to the Mongol combination of mounted archery and mobile heavy cavalry or an answer to the Mongol operational art, a modernist combination of highly mobile war and outstanding command and control. Long before Napoleon the Mongols perfected the art of moving along separate axes to a central position for battle.

The descent of the "Tartars" must have seemed like a 13th Century slasher flick to the Europeans; sudden, bloody and supernaturally unstoppable. The little horsemen from central Asia must have been the Michael Myers of Kievan Rus: popping up put of nowhere to slash your throat, and nothing and no one could stop them. The flower of mittleeuropean chivalry tried to halt Subutai's invasion of the central European plain and were brutally defeated at the battles of Sajo River and Leignitz

that left what is today's Hungary, Poland and eastern Germany helpless against Mongol invasion.

And then Great Khan Ogedai died.

The Mongol tumans turned back into the steppes to raise a new great Khan. The next twenty years were marked by a succession of relatively strong but short-lived Khakhans that affected the political stability of the Mongol Empire if not the military skill. The northwestern border stabilized while major advances were effected in southwest Asia. Mongol forces under Hulagu overran Persian and much of the northeast edge of the Black Sea in the 1250's. Baghdad fell in 1258 and the Abbasid Caliphate was destroyed. The next year Hulagu pushed in Syria, with the eventual goal of the rich delta of the Nile. Waiting there were a new breed of Muslim soldier: the Mamluks.

The Mamluk system was originally designed by the Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad - trust Iraqis to come up with something simultaneously clever and dangerous - to replace an older slave-soldier setup (the "Ghulam") that had proved a trifle difficult when the Turkish POWs of the Ghulam whacked four caliphs in a row in the 9th Century.

The new organization was staffed by captured children, often from the Caucasus or Kipchak Turkey, raised as soldiers and loyal retainers of the Islamic ruler...at least that was the plan. Four hundred years later the Mamluks, given their monopoly on disciplined military force, were vying for power in several Islamic states. They got in in Egypt in 1250 through a complex and murderous scheme that involved marriage, assassination and drowning in a bathtub. The Egyptian Mamluks were a fun, if lethal, bunch of folks.

They were also hell on hooves; former steppe riders, armed and organized as light horse archers and medium- to heavy lancers. Their organization was as good as the Mongols, and they were close to the champions' weight in the saddle. In 1250 the Egyptian Mamluk forces bitchslapped Louis IX

They were also hell on hooves; former steppe riders, armed and organized as light horse archers and medium- to heavy lancers. Their organization was as good as the Mongols, and they were close to the champions' weight in the saddle. In 1250 the Egyptian Mamluk forces bitchslapped Louis IX

and diced up his 15,000 Crusaders at the Battle of Fariskur.

This battle predates the Further Adventures of the Mamluk Guys, but I hope I'm not giving anything away if I tell you that the ended up driving the Mongols out of Syria, crushing the last remnants of the Crusader state and even resisting the Ottomans for a while longer than most. Tough bastards.

But the main point here is that by 1259 they were ready to meet the Mongols head-on.

The Campaign: Key to the Ain Jalut campaign was a dead guy: Mongke, former Great Khan of the Mongol Empire and surprised corpse in August, 1259; either shot by a Song archer, smooshed by a trebuchet projectile (my personal favorite: I have this Wile E. Coyote image of the shadow growing as Mongke looks up and has just time to mutter the Mongol equivalent of "What the..?" before the Acme Trebuchet Stone reduces him to road pizza) or possibly cholera or dengue fever or...

Whatever. The Khan Hulagu, who had been intent on driving into Egypt, had to turn his riders around and head for the steppes for fight out the succession. He left the Mongol equivalent of a corporal's guard under Kitbuqa to finish the Mamluks. What was to worry? No one had stood up the tumens before.

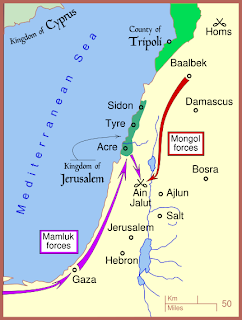

Whatever. The Khan Hulagu, who had been intent on driving into Egypt, had to turn his riders around and head for the steppes for fight out the succession. He left the Mongol equivalent of a corporal's guard under Kitbuqa to finish the Mamluks. What was to worry? No one had stood up the tumens before. The weeks preceding the battle were a novel's worth of scheming and double dealing. Kitbuqa tried to enlist the Crusader states against their old enemies but was frustrated by a papal envoy. In turn, the sad little rump of the Kingdom of Jerusalem (now with 100% less Jerusalem!! and, in fact, based along the Levantine coast around Acre and Sidon) allowed the Mamluks to use their territory to swing north and west around the Mongol tumens advancing into the valley of the Jordan River. The two forces met just south of the old city of Galilee in the first week of September, 1260.

The weeks preceding the battle were a novel's worth of scheming and double dealing. Kitbuqa tried to enlist the Crusader states against their old enemies but was frustrated by a papal envoy. In turn, the sad little rump of the Kingdom of Jerusalem (now with 100% less Jerusalem!! and, in fact, based along the Levantine coast around Acre and Sidon) allowed the Mamluks to use their territory to swing north and west around the Mongol tumens advancing into the valley of the Jordan River. The two forces met just south of the old city of Galilee in the first week of September, 1260.The Sources: We have only one source for infomation about Ain Jalut: Jami'u't-tawarikh, the "Compendium of Chronicles". This history was comissioned near the turn of the 13th Century by Khan Ghazan, the Mongol ruler of what was known as the Ilkhanate, the brief-lived Mongol principate which encompassed most of what is today the central Middle East and Turkey.

The author, high in the court of the Ilkhanate, likely had access to official Mongol correspondance, and given the proximity of the writing to the battle could have interviewed Mongol survivors. Elsewhere in his manuscript Rashid is a reliable reporter and his historical accounts of Genghis Khan's time tally with his source material known from Chinese records. His pro-Mongol bias is apparent from the text, but the events of Ain Jalut were so straightforward that he could do little to make the outcome look better for his patron. One should take the speeches of Kitbuqa with a grain of salt, however, given how unlikely the chance that any of the Mongol commander's close associates survived to report these orations.

The author, high in the court of the Ilkhanate, likely had access to official Mongol correspondance, and given the proximity of the writing to the battle could have interviewed Mongol survivors. Elsewhere in his manuscript Rashid is a reliable reporter and his historical accounts of Genghis Khan's time tally with his source material known from Chinese records. His pro-Mongol bias is apparent from the text, but the events of Ain Jalut were so straightforward that he could do little to make the outcome look better for his patron. One should take the speeches of Kitbuqa with a grain of salt, however, given how unlikely the chance that any of the Mongol commander's close associates survived to report these orations.The Engagement: Here's how the Compendium describes Ain Jalut:

"Quduz stationed his troops in ambush and, himself mounted with a few others, stood waiting. He clashed with Kitbuqa and his several thousand cavalry, all experienced warriors, at Ayn Jalut. The Mongols attacked, raining down arrows, and Quduz pulled a feint and started to withdraw. Emboldened, the Mongols lit out after him, killing many of the Egyptians, but when they came to the ambush spot, the trap was sprung from three sides. A bloody battled ensued, lasting from dawn till midday. The Mongols were powerless to resist, and in the end they were put to flight."

Plain enough, and consistent with steppe warfare of the day: the forces engage, the Mamluks feign flight, draw the Mongols into the kill zone and then close the kill sack. Qutuz seems to have used the terrain of the valley of Ain Jalut cleverly to conceal his ambush force.

From the comment in the Compendium noting the bloody progress of the "feigned" retreat ("killing many of the Egyptians"), it has been surmised that the Mamluk flight may have been, or have become, as much real as tactical. The Wiki article states that "(t)he Mamluks drew out the Mongol cavalry with a feigned retreat, but were almost overwhelmed by the savage Mongol attack." I am curious to know what source this assesment is based on, since the Compendium makes no such claim, but from the original some degree of tactical disintegration seems plausible. Even when they weren't at the top of their game the Mongol horsemen were mad, bad and dangerous to know.

From the comment in the Compendium noting the bloody progress of the "feigned" retreat ("killing many of the Egyptians"), it has been surmised that the Mamluk flight may have been, or have become, as much real as tactical. The Wiki article states that "(t)he Mamluks drew out the Mongol cavalry with a feigned retreat, but were almost overwhelmed by the savage Mongol attack." I am curious to know what source this assesment is based on, since the Compendium makes no such claim, but from the original some degree of tactical disintegration seems plausible. Even when they weren't at the top of their game the Mongol horsemen were mad, bad and dangerous to know.

The other rather surprising aspect of this battle is that Kitbuqa, no fool and an experienced Mongol officer, would have fallen into the old "feigned flight and ambush" trap. We are told by Rashid elsewhere, though, that he was "hot-tempered" and had lost a grandson to the forces of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem that had caused him to take and sack the city of Sidon. Perhaps he was overconfident, or made the un-Mongol mistake of getting too close to the actual fighting and lost control of the tactical situation.

Whatever he cause, he certainly paid for it. The Compendium continues:

"Kibuqa Noyan kept attacking left and right with all zeal. Some encouraged him to flee, but he refused to listen and said, "Death is inevitable. It is better to die with a good name than to flee in disgrace. In the end, someone from this army, old or young, will reach the court and report that Kitbuqa, not wanting to return in shame, gave his life in battle." (However his horse is brought down and he is captured by the Mamluks)We have no real idea of the losses on both sides. The entire Mongol tumen(s) was destroyed; probably 80-90% of the 20,000-some Mongols were killed. Mamluk losses were described as "heavy", suggesting that several thousand men were killed, probably in the initial Mongol penetration and pursuit.

Near the battlefield was a reed bed in which a troop of Mongol cavalrymen was hiding. Quduz ordered fire thrown into it, and they were all burned alive. After that, Kitbuqa was taken before Quduz with his hands bound.

"Despicable man," said Quduz, "you have shed so much blood wrongfully, ended the lives of champions and dignitaries with false assurances, and overthrown ancient dynasties with broken promises. Now you have finally fallen into a snare yourself.""If I am killed by your hand," said Kitbuqa, "I consider it to be God's act, not yours. Be not deceived by this event for one moment, for when the news of my death reaches Hulagu Khan, the ocean of his wrath will boil over, and from Azerbaijan to the gates of Egypt will quake with the hooves of Mongol horses. They will take the sands of Egypt from there in their horses' nose bags. Hulagu Khan has three hundred thousand renowned horsemen like Ket Buqa. You may take one of them away."

Quduz order his head severed from his body."

Ironically, while Quduz was the boss of the Mongols, Baibars was the boss of him, supposedly having him whacked while the luckless Quduz was out hunting. Baibars went on to expand and consolidate Mamluk power in the Levant, crushing the sad remnants of the Crusader kingdoms and establishing Egypt as a major center of the Islamic world.

Ironically, while Quduz was the boss of the Mongols, Baibars was the boss of him, supposedly having him whacked while the luckless Quduz was out hunting. Baibars went on to expand and consolidate Mamluk power in the Levant, crushing the sad remnants of the Crusader kingdoms and establishing Egypt as a major center of the Islamic world. Outcome: Complete tactical Mamluk victory; part of strategic Mamluk success (with Homs and several other Mongol defeats in the 1260s) in pushing Mongol Ilkhanate back to the northeast out of Syria and the Palestinian Levant.

Impact: While relatively minor in itself, the real implications of Ain Jalut came later, when Hulagu was unable (because of intercene warfare between the Ilkhanate and the delightfully named "Golden Horde", carefully fomented by the Islamic powers of Egypt and the Gulf region) to avenge the defeat. In fact, the three tumans he despatched were decisively beaten by our treacherous friend Baibars at the First Battle of Homs, the two defeats between them costing the Ilhanate most of what is today Syria.

In particular, Ain Jalut was the "high water mark" of the Mongol period. Before Ain Jalut the khanates were pushing out everywhere in the Middle East and Europe. Afterwards, the empire disintegrated into competing khanates that were unable to keep up politically or militarily with a risingly vigorous and expansive Europe. The battle did not accomplish this as much as it signalled the end of the "Mongol Era" in European history.

Touchline Tattles: One of the fascinating little snipbits I read about this engagement was that the Mamluks used "hand cannon" - probably an invention passed from China to the Middle East by the Mongols themselves - to some effect(?) during the battle. The textural references speak of the cannon frightening the Mongol horses, which would be unexceptional given the surprise effect of a masked battery of these blunderbusses on an unprepared horse and rider.

Touchline Tattles: One of the fascinating little snipbits I read about this engagement was that the Mamluks used "hand cannon" - probably an invention passed from China to the Middle East by the Mongols themselves - to some effect(?) during the battle. The textural references speak of the cannon frightening the Mongol horses, which would be unexceptional given the surprise effect of a masked battery of these blunderbusses on an unprepared horse and rider. The real oddity is the appearance of gunpowder weapons during the "high water mark" of the Mongol empire. Within another four hundred years the descendents of these "hand cannon" would prove the first effective solution to the steppe nomad combination of pony and compound bow. The revolution that would end the day of the man on horseback was very inaccurate and very new at Ain Jalut, but the powder smoke drifting away on the wind that day was the first hint of the bonfire of the knightly vanities.

The real oddity is the appearance of gunpowder weapons during the "high water mark" of the Mongol empire. Within another four hundred years the descendents of these "hand cannon" would prove the first effective solution to the steppe nomad combination of pony and compound bow. The revolution that would end the day of the man on horseback was very inaccurate and very new at Ain Jalut, but the powder smoke drifting away on the wind that day was the first hint of the bonfire of the knightly vanities.

172 comments:

Post a Comment